I've probably had two concussions in my life. The first was when I was 12, in a football game. I went back to pass, got hit from behind, and woke up on the sidelines. The next came many years later, when, in trying to teach my son to skateboard, I decided to teach myself first – not smart. I didn't think of either of these injuries as significant, as what they might be or might mean. In one, I was knocked out; in the other, for two weeks I felt like I'd had the stuffing kicked out of me. I got better. No big deal.

I began thinking more about concussions when Bobby Kuntz died about six years ago. He had been a player for the Toronto Argonauts and Hamilton Tiger-Cats, a running back and linebacker at a time when CFL players, the talented ones, played both offence and defence. And he was fearless. When he hit the line, though he was small, it was with the echoing thwack of a car crash, a sound different from everyone else's. In kids' games, I used to put my head down and run into the line pretending I was Bobby Kuntz. He died at age 79 – according to news stories, after suffering from Parkinson's disease the last 11 years of his life.

Then there was Ollie Matson. He had been a Hall of Fame running back in the NFL with the Cardinals and the Rams. With his speed and ability to find one more direction than his tacklers could, he seemed to elude the worst of the contact that Bobby Kuntz relished. He, too, died six years ago, of what articles described as "dementia complications."

I began to read tribute articles all the way through, the great stuff up front, the details of postcareer life coming near the end. Many players I'd watched as a kid, I realized, had lived long years at the ends of their lives with conditions others most often experienced in much older years.

Then there were the careers in more recent times that I watched end early. Steve Young and Troy Aikman in football; Eric Lindros, Pat LaFontaine, Paul Kariya, and many others in hockey. People who, their play having been diminished by their head injuries, had ceased to be superstars long before age would have done them in.

I started writing articles about concussions. I gave talks and interviews. I interested some people in organizing concussion symposiums in their cities and towns – in Peterborough, Calgary, Regina, Vancouver, Charlottetown, Guelph, even Dryden, Ont. (an event organized in her hometown by a student of mine at McGill University, where I was teaching at the time).

The events lasted a full afternoon or evening. The format was the same: Local athletes told their own stories of the athletic effects and life effects of their concussions. Local doctors told of the people they treated, about what they knew and didn't know, and hoped some day would. Local hockey/sports "people" – administrators, officials, hometown stars, the most respected such voices in town, responded to what they had heard from the athletes and doctors, then told of what their leagues and teams were doing and what they might do in the future. In the audience, in significant numbers, parents, coaches and interested citizens listened, asked questions, and left, as they told me, with much greater "awareness" of the problem.

But in the meantime, years were passing. Players young and old continued to be injured, retired NHL players continued to show life-altering symptoms, exciting new research was being done, more things were happening.

But little was changing.

To some, concussions, as an issue, came to seem confusing and tired. "Confusing" because so many people who seemed to know were saying so many different things: It's the equipment. We need a better helmet, they said. No, we don't; yes, we do. It's the rules. We need tougher penalties. It's the science. We don't know enough. And, of course, when awareness isn't enough, the only answer seems to be more awareness. More articles, more research, more conferences, until the issue does come to seem "tired" because so much had been said and so little has happened.

For parents with kids in the game, none of this got tired. For the media, though, it did.

I learned, the hard way, that awareness has its limits.

Scientists, in making public their work, generate awareness. The news media, in their reporting, do the same. Both assume, we all assume, or maybe just hope, that if we build the mountain of awareness high enough, if its very existence is so clearly unacceptable and wrong, something will be done. They – a league, the courts, government, somebody – will do something. But often, they don't. And they especially don't when, just as with other seemingly unmovable problems – racism, inequality, climate change – they don't know what to do. So first, they don't see what is there, then they ignore, then they doubt, then they fight back, then they create doubt, then they manage. They don't solve. Awareness is only a step along the way. It is not the final step.

This had to be about action, making decisions and implementing them. And not just doing something – anybody can do something – but something that is the equivalent to the magnitude of the problem. So I stopped writing articles. I stopped doing symposiums. I stopped giving speeches, except when I felt an absolute obligation to say yes. I could see what was wrong. I could say what was right. But what did that matter? I had no interest in generating more awareness. This was about better decisions.

That's why I decided to write Game Change: The Life and Death of Steve Montador, and the Future of Hockey, and why I've written it this way. It's the story, first of all, most of all, of a life – Steve Montador's, because it's a life that gives concussions meaning, that makes clear the stakes for all of us, players, coaches, hockey officials, parents, citizens – and that makes clear, as well, the consequences of what we do or don't do, about concussions.

It's also the story of science, of knowing better today than yesterday, but of never knowing for sure, because science never knows for sure, because what it knows today is only a placeholder for what it will know tomorrow. But games are played today – so what do we do? Based on the best science we have at this moment, today, what decisions do we take?

And this is also the story of a game, of how it has evolved, how in its beginnings in 1875 it would have been unrecognizable to today's eyes, and how hockey today would be unimaginable to those first players more than a century ago. It's about how a game has changed, and the effect of these changes, on concussions and head injuries, and about how the game can change again.

My book is about all of these things together, interwoven, because it is only inside the full story that answers can be found, that the real can be separated from the bogus – focused on, and acted upon.

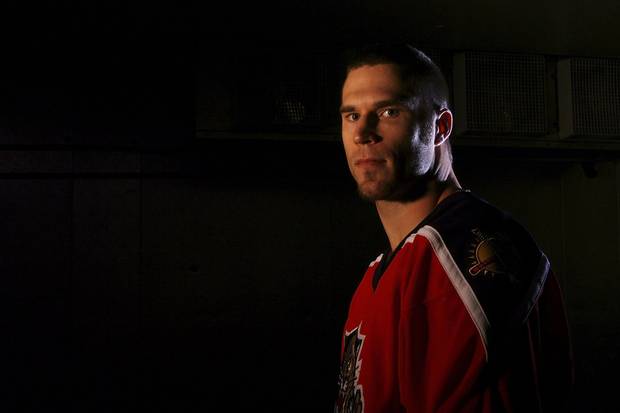

Over 10 seasons, NHL defenceman Steve Montador – shown at right in 2004, playing for the Calgary Flames – played for six NHL teams in 571 games. He died in 2015 at the age of 35.

MIKE BLAKE/REUTERS

Head injuries took a heavy toll on the Canadian defenceman’s health: After his death, analysis of his brain found chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative condition linked to concussions.

DOUG BENC/GETTY IMAGES

Our great good luck is that in hockey, different from football, there are clear, absolutely doable answers. These answers begin where the problem begins, with hits to the head. A hit to the head is a bad thing. Many hits, hard hits, are very bad things. Here is where we start. Here is where we focus. The issue isn't whether a hit is intentional or accidental, whether a player's head is up or down, targeted or not, whether the hit comes from a shoulder, an elbow or a fist. The brain doesn't distinguish. It is about the hit, period. It is about the player being hit, not the hitter; the effect, not the cause.

So, at the core of every decision made about concussions is a singular understanding: No hits to the head – no excuses.

And at the core of the obligation to make those decisions and act is another understanding: The risk to the game's players is not fair, not right, and not necessary.

These last two words are crucial – not necessary. Lots of things in life aren't fair or right, but no matter what we do, they seem beyond us. We keep trying, and don't give up, but until we find answers, we live with them. We get on with things.

We don't need to do that here. Yes, concussions, life-transformng brain injuries, can happen anywhere, any time, to anyone. They will always occur. But they can be reduced immensely. That is the point. What we have today in hockey is not necessary. It doesn't have to be. There are steps we can take. This is what makes taking action on this, doing what needs to be done, exciting, and inaction inexcusable.

It begins with a simple ripple – no hits to the head. This ripple then runs backward, getting bigger, until it becomes a wave. In today's NHL, a stick to an opponent's face is a penalty – automatic – no excuses. A puck shot into the crowd in a team's defensive zone is the same, a penalty – automatic – no excuses. No big deal. Players adapt. The game goes on.

It can be the same with head hits. The result: a game that is just as exciting and challenging and compelling to play and to watch, and a game that is safer. If you have any doubts about this, just turn on any NHL game on TV and watch.

I did that a few days ago for the opening game of the season between the Winnipeg Jets and the Toronto Maple Leafs. The first 10 minutes were breathtaking; the rest of the game was almost as good. The pace, the puck zipping from stick to stick, players turning, turning again, creating something when nothing was there. It was unbelievable. And as I watched, I found myself looking for other things as well – I didn't intend to – for head hits, how many there were, where they happened, why, and who delivered them. There were almost none, by anybody, anywhere.

Later, I asked myself: If even these few head hits were called as penalties, how would the game not be the game? How would the play of it, and our enjoyment of it, be affected if they weren't there? I came away with my answer: Not much. In fact, likely not at all. Players and coaches adapt. That's what they do, in every game, in every situation of every game, against every opponent. Presented with something different, they find new answers. They would here, too. The game would still be the game, except fewer players would have head injuries, and fewer players would have their careers and future lives put in doubt.

Tonight, any night, watch for yourself.

The NHL logo looms behind league commissioner Gary Bettman.

CARLO ALLEGRI/REUTERS

Gary Bettman is the decision-maker in hockey. Not the NHL's Board of Governors who employ him; not the NHL Players Association and its head, Don Fehr; not the International Ice Hockey Federation, not Hockey Canada, USA Hockey or any other organization or person anywhere. Others administer; they make local decisions. Commissioner Bettman makes, or effects, all the important ones. If change is to happen, he will implement it.

But there is one other voice that hasn't yet been heard, and that might have some effect.

More than a century ago, modern life presented us with a new problem – drinking and driving. At the time, it was mostly a problem of boys and men. They were the drivers. And for decades, no matter how many men, women, boys and girls were killed by drunk drivers, one piece of conventional wisdom stopped any action in its tracks – "Boys will be boys." Boys, of all ages, will drink. Boys, of all ages, will drive.

Except, after tens of thousands of deaths, some mothers decided that this wasn't good enough. Boys and men will do both, but they don't have to do both together. Mothers Against Drunk Driving was born, and has achieved what didn't seem possible. These mothers may not have known what it's like to "be boys," but they did know something about kids and growing up and futures. They decided they had a right to feel what they did, and a right to do something.

They acted.

What about the mothers of hockey players? Just as the MADD mothers had to deal with "Boys will be boys," these mothers have been told that hits to the head are "just part of the game." And, besides, what do they know? They never played the game.

But these mothers, too, know something about kids and growing up and futures. Some day, maybe soon, these hockey mothers will realize they have a right to feel what they do, and a right to do something. They will realize they have a voice. The wives and partners of NHL players, and of athletes in other sports, are beginning to understand this now. They love their guys. They're not interested in spending their opportunity-filled futures together not able to do and enjoy so many things. They didn't sign up for this.

Imagine a Mothers Against Head Hits. MAHH. Wives and partners, too. Imagine if these mothers, wives and partners, in all sports, not just hockey, no longer accepted the old wisdom, and fought back. Imagine their rallying cry: No head hits – no excuses.

It's all so doable. In hockey, there are answers. It's why the last chapter of Game Change – where we go from here, and how – is by far the longest in the book.

In these past few days, I've sent copies of the book to people who helped me in writing it and who have worked for years with dedication in the field of brain injuries. On my inscription to them, I write: "And now the work continues – and begins."

SPORTS AND HEAD INJURY: MORE FROM THE GLOBE