Painting's last big hurrah was 30-plus years ago with the ascension of the so-called Neo-expressionist/New Romantic "movement." Painters have kept on painting since, of course, and occasionally a pundit, sensing an apparent trend, will bust a catchphrase ("Zombie formalism," anyone?). By and large, however, the medium-based, past-haunted idiom that is painting proceeds these days without any overarching aesthetic or ideology. In a realm crowded with video art, photo-based art, installation art, identity/gender art, text-based art and performance art, painting's vitality and importance are now decided almost painting by painting.

So, with this context in mind, it's rather refreshing to take in A New Look: 1960s and '70s Abstract Painting at the AGO, now up at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. Not only are its 11 works superb for the most part (each is drawn from the gallery's permanent collection), the exhibition evokes an era when painting was still top dog, bestriding the then-narrow art world like a Colossus. Yes, there were anxieties and debates back then about styles of painting and where painting needed to go to remain modern and relevant – but there was no existential crisis about its continuing primacy and validity. Hell, no … at least not when you had a chain-smoking, alcoholic critic/consultant/advocate such as New York's Clem Greenberg pontificating and pointing away.

Greenberg's been dead almost 22 years, while the height of his influence waned 25 years before that. But he haunts our often bewilderingly pluralistic art world still and the AGO exhibition in particular. Indeed, all seven painters in A New Look – five Americans (Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis, Frank Stella, Gene Davis, Helen Frankenthaler) and two Canucks (Jack Bush, Kenneth Lochhead) – were among the 31 artists featured in a 1964 travelling exhibition curated by Greenberg. Called Post Painterly Abstraction, the show's 90 or so works berthed at a total of three venues that year, the last, in late fall, being the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the AGO).

Post Painterly Abstraction (the term was coined by Greenberg to signal a break with what he called “the turgidities of second-generation Abstract Expressionism”) was Greenberg’s way of making real what he’d been writing about in such much-discussed essays as Modernist Painting, from 1961. Known by this time for his prescient championing of Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Hans Hofmann and other abstractionists, Greenberg believed the modernist agenda was forcing each art to inquire into (and act upon) just what was essential to “its area of competence.” Painting, to his eye, was becoming progressively purer, losing its functions as a mirror/prism/window on this world, throwing off figuration, perspective, three-dimensional semblances, narrative conceits to become an exploration of the push and pull of shape, line and colour on a flat surface.

It was, needless to say, a pretty severe aesthetic and many artists chose not to follow it, opting instead for what Greenberg derided as “novelty art.” (The prime example of this in his heyday would have been pop art. And to be fair, Greenberg was not altogether a strict adherent to his own orthodoxy, showing during his lifetime a great fondness for representational works such as the nude paintings of Horacio Torres and the landscapes of Canada’s Dorothy Knowles, Patricia Service and Ernest Lindner.)

Of course, just because someone with great authority and powers of ratiocination says something is going in a certain direction or should go that way is no determinant it will. The history of art is littered with discarded discriminations, with prognosticators and taste-makers whose visions and analyses came to naught or were superseded by other vogues. Greenberg seems to have made a bet on art, only to have artists – stubborn, feckless, impure, distractable artists! – let it (and him) down. Perhaps he should have taken Duchamp’s famous credo “I don’t believe in art; I believe in artists” closer to heart.

Still, after looking at the spaciously installed large paintings that make up A New Look, it’s hard not to vouch for the Greenberg ethos. To contemporary eyes, their pictorial strength is so self-evident, so enduringly fresh, you have to chuckle at those pundits who a half-century ago deemed Post Painterly Abstraction (both the style and the exhibition) a failed “rescue action for quality” against the “turgidities” of certain kinds of abstraction on the one hand and the vapidity of “newfangled art” on the other.

Numerically, Bush, Louis and Noland dominate the exhibition, with respectively three, two and two paintings each. Louis would have been represented by three, says Kenneth Brummel, 39, the AGO’s new assistant curator of modern art and a self-described “student of Greenberg” whose M.A. thesis was on Noland. However, the Louis that Brummel wanted, a majestic “veil” painting from 1958, was, at 240 centimetres by 430, simply too big to position adequately with the others. (Brummel also was keen to hang something by another Greenberg stalwart, Jules Olitski, but again size was the issue.) Nevertheless, the Louises that are here are top-notch, especially 1962’s I-98, its flushed alignment of nine stained vertical bands on a creamy ground a highway of colouristic lyricism.

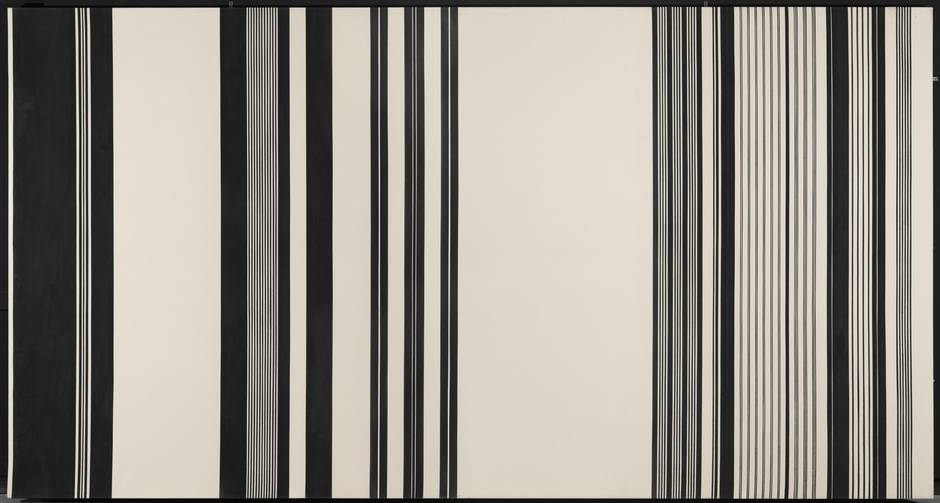

The exhibition’s biggest (re)discovery is Gene Davis’s Black Panther, from 1970 and last seen at the AGO more than 12 years ago. It’s a huge thing, occupying one wall in the two rooms the AGO has allocated for A New Look. From a distance its marshalling of crisp black lines on precisely calibrated swatches of white looks rather like a blow-up of a bar code, minus the numbers. Closer, it’s a much more active, quivery work. I don’t think you’d be far wrong to see it as simultaneously a riff on op art (a term coined by Time magazine the same year as Greenberg’s Post Painterly show), a metaphor for the fluidity of U.S. race relations and a sort of tidying up of what Brummel calls “the thick, frayed brushstrokes” of Franz Kline and the bulbous forms of Robert Motherwell, both of whom worked largely in black and white.

Small as A New Look may be quantitatively, it packs a substantial wallop to the eyes. See it, too, as a harbinger of other Post Painterly shows at the AGO possibly focused on individual artists (such as Olitski) or other group configurations. Post Painterliness “is one of the strengths” of the AGO archives, Brummel notes, adding, “I have in no way exhausted our holdings with this permanent collection display.”

A New Look: 1960s and ’70s Abstract Painting at the AGO runs at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto through March 27.