Hundreds of bargain hunters line Bloor Street in midtown Toronto in September, 1961, waiting to enter Honest Ed's.

Places matter. Buildings matter. But which ones? Which ones are worth keeping, and which ones are we sorry to have lost?

It’s a hard question to answer in 2019. Today, that conversation is more complicated. For one thing, “heritage” has a broader meaning.

“A lot of people think immediately of those iconic buildings, like the Van Horne Mansion” in Montreal, says Chris Wiebe, manager of heritage policy for the National Trust for Canada. “But over the last few years, the view of the heritage community has expanded to look at more modest places that are no less important to people.”

Grain elevators in Saskatchewan and the Honest Ed’s discount store have become objects of veneration.

Fifty years ago, things were simpler. As the historic preservation movement took root in North America, it was clear to those involved what needed to be saved: Grand buildings of the late 19th century and early 20th century. These were under assault from the linked forces of “urban renewal.” Civic and corporate leaders in many cities saw the need for reconstruction that would make room for the car and replace older, supposedly obsolete buildings with Modern ones.

But that same era, of the 1960s, is now history. The postwar period brought tremendous change in society and in architecture, and many places of that era are now aging and vulnerable. Some are already gone and are sorely missed.

Looking back over the past century, here are some of the places that we miss most.

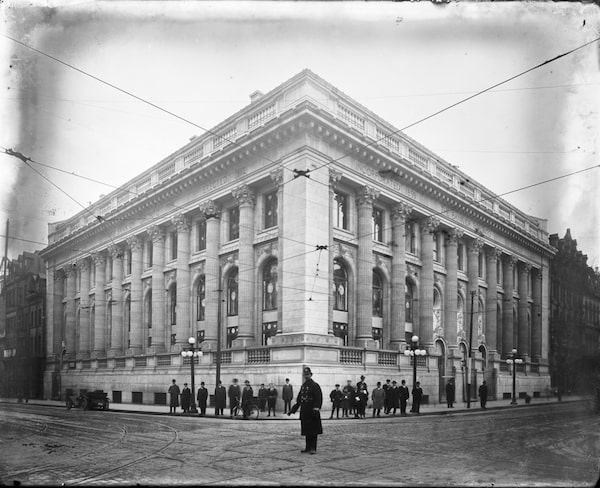

Bank of Toronto, 1912-1964

The Bank of Toronto’s headquarters were at least replaced with another masterpiece when it was torn down.Library and Archives Canada

When the Bank of Toronto built its headquarters at King and Bay streets in 1912, it went all-out: the bank hired the New York firm Carrère & Hastings to create a grand example of French Renaissance classicism, which stood back from behind 21 Corinthian columns of grey Tennessee marble. A double-height banking hall decked out with marble and bronze was one of the city’s great spaces. But in the 1960s, the newly formed Toronto-Dominion Bank tore it down for a new complex by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. This building – itself a masterpiece – “stands as a ghostly reminder of lost splendour,” wrote the historian William Dendy in Lost Toronto. Eight columns from the bank made it to the suburban Guild Inn, where they’ve stood ever since as part of an outdoor stage.

Van Horne Mansion, Montreal, 1870-1973

The demolition of Montreal’s Van Horne Mansion in 1973 spurred historical preservation efforts in the city and helped Phyllis Lambert acquire another historic property, Shaughnessy House.unknown/Handout

The destruction of this mansion was an important boost for the cause of historic preservation in Montreal. Located in the Square Mile, it had been expanded and redecorated in elaborate Art Nouveau style by the railway executive William Van Horne. (The designer was Louis Tiffany’s partner, Eugene Colonna.) The politics were complex – this was, after all, a bastion of Anglo wealth. But the demolition of the mansion spurred local preservation efforts and helped Phyllis Lambert to acquire the grand Shaughnessy House, now part of the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Ontario Place Forum, Toronto, 1971-1994

The Ontario Place Forum, seen in 1978, was brought down by austerity and privatized. Today, it is a concert venue named after a beer company.Dennis Robinson/The Globe and Mail

This was the centrepiece of Ontario Place, the waterfront park that was Ontario’s answer to Expo 67. Architect Eberhard Zeidler and landscape architect Michael Hough designed the theatre to have no bad seats; its 3,000 perches were tightly gathered in a circle, and a rotating stage provided equal views. The fabric tent that sheltered the stage (inspired by the German visionary Frei Otto) gave the place an intimate, camp-like feeling. This popular favourite never saw its 30th birthday, brought down in the name of austerity and privatized as a concert venue named for a beer company. Public, fantastical and weird, it captured the best of postwar Canada.

Shell Oil Tower, Toronto, 1955-1985

Toronto’s Shell Oil Tower, seen in 1973, was demolished in 1985 to accomodate the racetrack for what was then called the Molson Indy.Barrie Davis/The Globe and Mail

Just as a bell tower defined the heart of a Renaisssance Italian village, this observation tower defined the heart of Exhibition Place. In the 1960s, fairgrounds were still important public places, and George Robb’s glass-walled steel-structure creation defined a new era for this one. In 1985, Globe and Mail critic Adele Freedman wrote “it was a landmark which might be said to have passed into collective ownership.” But it was demolished that year, to accommodate the track for the Molson Indy. Cars rolled over architecture, not for the first time.

B.C. Binning House, West Vancouver, 1941-?

B.C. Binning House, seen in 1951, still stands today, but a new owner has plans to redevelop the site, which one critic calls ‘arguably the most important of all to save.’Graham Warrington/Canadian Centre for Architecture

Many of the West Coast’s greatest buildings are private houses, and therefore obscure. This one had more of a presence than most; artist Bertram Charles Binning (who designed it) and Jessie Binning hosted salons that brought locals to hear international luminaries such as architect Richard Neutra.

The house still stands. But a new owner has plans to redevelop the site. “Of all the early modernist houses now in danger, this house and its surrounding site is arguably the most important of all to save,” says the critic Adele Weder, co-author of a book on B.C. Binning. “Built in 1941, it was one of the first Modernist houses in the country. … Its architectural features present us with an encyclopedia or early modernism, and its subtly canted walls, embedded murals and engagement with its site make it a unique work of art.”

Corry Block, Ottawa, 1903-1967

The Corry Block on Rideau St.Library and Archives Canada

This flatiron-shaped eight-storey office building stood at the centre of the city, next to Union Station. Its spare Edwardian Classical architecture, by local E.L. Horwood, was quite forward-looking for the time, and the tower – capped with a neon sign for local appliance manufacturer Beach Foundry – was a landmark. However: “It was demolished by the National Capital Commission to make way for an on-ramp to Colonel By Drive,” says Alain Miguelez, manager of policy planning of the City of Ottawa. “Had it survived, it would have completed the classical, Beaux-Arts enclosure of the eastern edge of Confederation Square.”

Hogan’s Alley, Vancouver, 1900-1967

Hogan's Alley was once the hub of Vancouver's black community.City of Vancouver Archive

For most of a century, the hub of Vancouver’s black community was in Strathcona, clustered around a corner known as Hogan’s Alley. Squeezed into this working-class area by widespread discrimination, this community – of about 800 at its height – established an African Methodist Episcopal church and a cluster of black-owned businesses. (The artist Stan Douglas has created an app and an installation that recreates the area as it was in the 1940s.) The community was displaced when the city routed highway infrastructure – ramps to the Georgia Viaduct – through the area. This is a story with analogies in Halifax’s Africville and dozens of American cities. The non-profit Hogan’s Alley Society is now working to see this history recognized.

Eaton’s, Winnipeg, 1904-2003

While downtown Winnipeg has many vacant properties to choose from, the one selected to be demolished for an arena was the old Eaton’s department store, a Chicago-style building designed by local architect John Woodman.Robert Tinker/The Globe and Mail

This massive department store on Portage Avenue was an important place in Winnipeg life. It was also a formidable building, a complex of Chicago-style architecture designed by prominent Winnipeg architect John Woodman. Rich in social and architectural history, full of valuable materials that could have stood up for decades to come, it was instead demolished for an arena, now the Bell MTS Place. In a city whose downtown still has many vacant lots, this was and remains an unnecessary loss.

Capitol Theatre, Saskatoon, 1929-1979

When Saskatoon’s Capitol Theatre was demolished in 1979 by an Alberta developer, the public outcry helped spur city council to pass heritage legislation the following year.Saskatoon Public Library

The 1920s Spanish Revival theatre by architect Murray Brown was an ornate and showy presence in the downtown here. And it was a place where many locals not only saw movies and plays but also performed in local productions or attended graduation ceremonies. After an Alberta developer demolished the theatre in 1979, the outcry helped spark Saskatchewan to pass heritage legislation the next year.

Minaki Lodge, 1925-2003

The Minaki Lodge was rebuilt by the Canadian National Railway after a fire in 1925, but another fire in 2003 destroyed the hotel’s grand log structure.Ruth Bonneville/The Globe and Mail

Railway hotels are some of Canada’s best-loved buildings. This one in Northwestern Ontario, first built by the Grand Trunk Railway and rebuilt by Canadian National Railway after a fire in 1925, centred on a huge hunting lodge, designed by railway architect George Briggs and built with B.C. timber. The railways’ tourism pitch could be problematic – “most visitors want to explore this country where the Sioux and the Obijways fought for supremacy,” said a 1953 railway brochure – but the grand log structure was still beloved when it burned in 2003.

Alex Bozikovic

Alex Bozikovic