Cindy Sherman creates unsettling images of characters who seem familiar yet not quite nameable.Cindy Sherman/Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York

When Cindy Sherman was a girl growing up in suburban Long Island, N.Y., she had a suitcase full of vintage clothes, old family things she had rescued from the basement or discarded prom dresses she had bought for a dollar at a thrift store. More than 50 years later, the U.S. photographer still has her dress ups, but the collection has expanded: Her large Soho studio here, cluttered but well organized, features a rack of caftans and evening gowns, and carefully labelled drawers of wigs, prosthetics and props. Should Sherman be in need of a sequinned top, a plaid skirt or a fake breast, such items are close at hand.

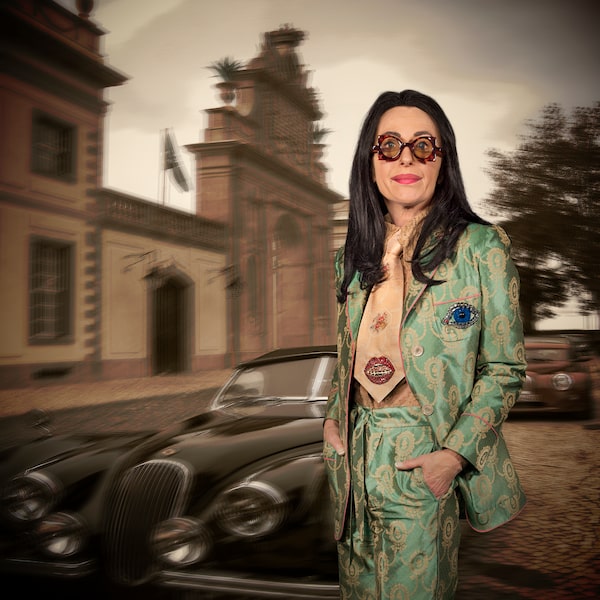

After all, Sherman is a master of disguise. One of the international art world’s most recognized figures, she has made a highly successful career of dressing up for her own camera, creating unsettling images of characters who seem familiar yet not quite nameable, whether they take the form of movie stars, socialites or clowns.

An immersion in the world of Cindy Sherman’s photography, at the Vancouver Art Gallery

More recently, Sherman’s experiments in the construction of image and identity have moved online. Her twisted versions of her own face reach almost 300,000 followers on Instagram as she toys with a photo editing app and turns the social media platform into her personal sketchbook. On the eve of a major retrospective organized by London’s National Portrait Gallery and opening at the Vancouver Art Gallery Saturday, her five-decade oeuvre seems to both predict and critique the selfie moment.

It’s not a parallel, however, that speaks to Sherman: “I bristle hearing people refer to my work as selfies. Because I don’t think of them as about the self,” the artist said during a recent interview in her studio.

Well, certainly not about herself. The very first thing a visitor wants to know about the oh-so-famous Cindy Sherman is what does the real woman actually look like? Still youthful at 65, petite, small-featured, pale and blonde, wearing no makeup and casual clothes, neither particularly beautiful nor unattractive. In short, Sherman is non-descript, the kind of person you could pass in the supermarket without a second glance, which may explain a lot.

Sherman says she bristles hearing people refer to her work as selfies, because she doesn't view them as about the self.Cindy Sherman/Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Her mother, a teacher, was 44 when Sherman was born; her father, an engineer, almost 50. She was at the bottom of a family of five children and she figures that dressing up was a way of attracting attention: “Hey, you guys! Don’t forget about me. If you don’t like me this way, how about this way?” the young Cindy seemed to ask.

“It was about erasing who I am and trying to come up with someone else,” she said. On the shelves in her studio, there’s a small framed photo of her and a friend dressed like little old ladies, kitted out quite convincingly in stiff dresses and old-fashioned hats as they gleefully totter along in ladylike pumps. It was snapped by a neighbour around 1966, when Sherman was about 12.

Adolescence didn’t stop this game-playing, but she replaced clothes with cosmetics.

“I got into transforming my face with makeup,” she said. “I was addicted to it in high school. To the point where I would put on makeup even if I was sick in bed. You had to be ready just in case somebody knocks on the door. I remember thinking I could never imagine being with somebody, being so comfortable with them, that I would let them see me without makeup.”

And, as she grew into adulthood, makeup’s transformative role became even clearer: “As a therapy maybe, to calm myself down, I would go into my bedroom and turn into somebody else. It wasn’t about trying to look better; it wasn’t an improvement on myself; it was really just was about becoming someone else.”

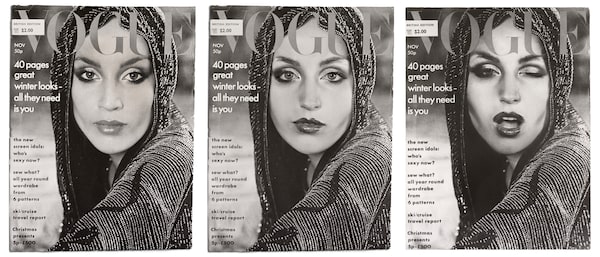

Sherman's work made oblique references to a variety of media and genres, from advertising and fashion magazines to pornography.Cindy Sherman/Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Unfortunately for the young Cindy, the 1970s, the so-called Me Decade, were all about being natural – no makeup, no bras, no hair dye. At university – she attended Buffalo State College from 1972 to 1976 – she was forced to seek herself. It was a difficult period during which she painted meticulous reproductions of images she found in magazines and had to repeat a required photography course she had failed.

A professor encouraged her to consider the camera as a tool and assigned the students the task of confronting their fears. Sherman recalled with a shudder the springtime frolics organized by the teacher, outings full of students shooting each other naked in nature. Now, she turned the camera on herself and tried photographing her body without clothes. Meanwhile, her boyfriend of the time, artist Robert Longo, suggested she start documenting her recurring disguises. A career was born.

In her early Untitled Film Stills series, begun soon after she graduated and moved to New York, she posed in costumes and makeup on sets she managed to erect in the confines of her shared apartment, reproducing the look of Alfred Hitchcock thrillers or the European art house cinema.

“The apartment I lived in was really funky, but I managed to decorate the bedroom with stuff I found at flea markets, and made it look like a little hotel room or whatever. … What I call the librarian [an image of a young woman in front of bookshelves] is just these metal shelves we had with art books and film books; I was just reaching up for a book. It was totally intuitive. I didn’t know what I was doing until I started seeing results.”

Those results, posing melodramatic female protagonists in a street, a doorway or a bed, suggest archetypal narratives of tragedy and betrayal, but never actually quote their sources nor tell their stories. These 70 photographs created between 1977 and 1980 seemed to celebrate the artificiality of the movies while deconstructing their portrayal of women, and they brought Sherman immediate attention from critics, curators and dealers.

By the 1980s, her work was becoming increasingly technically sophisticated. She moved into colour and began working with a green screen, placing rear projection backdrops behind her own costumed figure to create images that were overtly filmic in look. Over the years, she has made oblique references to any number of popular media or genres, from advertising and fashion magazines to pornography, and in her History Portraits of the late 1980s, she directly quoted from Western art, adding ridiculous prosthetic breasts or heavy wigs to images of kings and madonnas.

One of Sherman's painfully overdone matrons of her Society Portraits of 2008.Cindy Sherman/Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Like the grotesque clown faces she produced in the 2000s or the painfully overdone matrons of her Society Portraits of 2008, all of these images flag their falseness and their fakery, sometimes with nasty humour, other times with deep pain. If Sherman avoids condescending to her many sad or bizarre characters – and condescension is a distinct possibility with images such as those of the pretentious socialites – it is perhaps because she herself is the source material.

Sherman may be disguised in her work, but nonetheless she always runs the risk of making herself look foolish. So, inevitably perhaps, she has to respond to accusations that all these pictures of Cindy Sherman suggest a project that is self-centred or hubristic. It’s a charge she roundly rejects.

“If an actor like Meryl Streep is playing a role but you can still recognize her as Meryl Streep, you aren’t thinking, ‘oh my God, she is so narcissistic.’ You recognize she is playing a character,” Sherman said. This analogy with acting is one that occurred to her when she was working on her large-scale Murals in 2010 and worried about images in which her own face, albeit digitally tweaked, was more recognizable than in previous work.

Positioning her practice as something akin to a record of professional performance, she says: “I’m not role playing what I fantasize about or who I would like to have been. It’s more about hiding myself rather than revealing anything.”

Digital photography has revolutionized this chameleon-like practice, both speeding up Sherman’s process and expanding her imagery. In the Society Portraits, the Murals or the more recent and more retro Flappers, she can seamlessly position her characters against exotic (and digitally altered) backgrounds from European mansions to Western landscapes – or create a purposeful gap between the figure and the setting.

Some include multiple portraits in which several Cindys appear, while the oddly disjointed images of the murals, featuring awkward figures in elaborate and often urbane costumes visibly unconnected from backdrops of vast rocky expanses, move her work up to a heroic scale.

Sherman always works alone with her camera, trying out costumes, settings and poses. In the old days, she would use Polaroids to test the results on the spot, but often had to wait several hours for a lab to develop a film to know whether lighting, colour and focus were correct. If they weren’t, she would have to get dressed up all over again for another take. Now, the whole shoot can be completed without ever taking her makeup off, while both her image and her backdrops can be endlessly modified on the computer.

The whole process remains largely intuitive. Sherman will start with a wig or a prop and take it from there. “A lot of it is playing in front of the mirror, because I have a mirror right next to the camera, and then, while I am taking pictures, experimenting, sitting up, standing, moving, making different expressions. It is just through looking at it all on the computer that I start making decisions about what works.”

She often sources props and costumes right on her Soho doorstep, although the neighbourhood is changing, with the erratic gentrification of nearby Canal Street leading to retail closings. She’s recently lost a good stationer and a store that sold nothing but plastic.

Sherman always works alone with her camera, trying out costumes, settings and poses.Cindy Sherman/Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Online, however, materials and images are infinite. Her Instagram portraits have offered her a new layer of experimentation. She shoots her own face with her iPhone and then manipulates the image using Facetune, turning an app intended to improve one’s looks into an instrument of fun house grotesque, before adding in colourful backgrounds.

“I thought it was just amazing to see how far you can push it in a direction it wasn’t intended to go,” she said, adding she considers Instagram as a kind of sketchbook, rather than a medium for finished work. She has been working on reproducing the torqued and imploded faces that she can create with Facetune in other media, notably on tapestries that she is producing for a show in Paris next spring.

She was uninterested in social media until she discovered Instagram by chance, when friends asked her to follow them as they set off on a round-the-world trip. A year later she began posting during a trip of her own, to Japan, but kept the account private; it was only when she grew tired of sorting through the inevitable requests of potential followers that she made the account public – and began using Facetune.

Last year, the ranks of her followers swelled to a few hundred thousand from a few thousand after The New York Times wrote a story about the weird delights to be found @cindysherman.

It’s work that might seem like a sharp critique of a platform where vacuous social media hounds record their every new outfit, meal or vacation with stagey perfection, but Sherman is not one to discuss the social implications of her many disguises.

Question her about the larger impact of Instagram, and she answers that she doesn’t really follow many accounts. Wonder if digital technology subtly changes or perhaps intensifies her work, since the fakery is now both more seamless and more outlandish – two Cindys; twisted-face Cindy – but don’t expect much response. Ask about the trickery that might have produced one of the Social Portraits, of an aging urban cowgirl wearing heavy pancake makeup and a Stetson against a backdrop of digitally twirled leaves, and she replies: “I don’t want it to look too digital, but I don’t mind it looking somewhat digital. … I don’t want it to look too cartoony, but I could certainly airbrush out more wrinkles than I have. I have done some of that, but some of the makeup I use is meant to accentuate wrinkles and flaky skin.”

As she grows older, digital technology has been a life-saver, and not just for technical reasons.

“[Age] definitely limits what you can do,” she said. “When you are young, it’s easier to look older, whereas when you age …”

A decade ago, the Society Portraits were already bristling with the pathos of their subjects staving off time with beige foundation, plucked eyebrows and showy fashions. Someday, Sherman herself may become one of the frail old ladies she once pretended to be. That eventuality seems unlikely to stop a lifelong habit of dressing the part.

Cindy Sherman continues at the Vancouver Art Gallery from Oct. 26 to March 8.

Live your best. We have a daily Life & Arts newsletter, providing you with our latest stories on health, travel, food and culture. Sign up today.

Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor