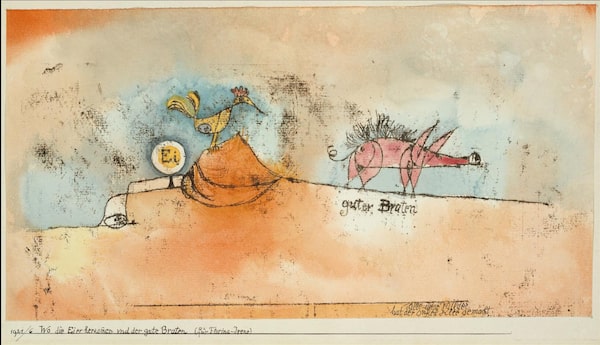

Where the Eggs and the Good Roast Come From by Paul Klee.The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Paul Klee exhibition now showing at the National Gallery of Canada begins with works created on the eve of the First World War during a brief but decisive trip the Swiss-German artist made to Tunisia. Accompanied by two members of the German expressionist group Blaue Reiter, Klee fell for the strong colours found in a hot climate. This collection, assembled by the art dealer Heinz Berggruen and donated to New York’s Metropolitan Museum in the 1980s, offers several choice examples from 1914, including a matching pair of paintings that quietly lays out the history of 20th-century art.

One is a watercolour view of St. Germain, the European quarter in Tunis, where a stucco house and walled garden is depicted as a series of interlocking planes; another, an untitled little watercolour no bigger than a birthday card, simply offers the planes themselves, just an abstract pattern of coloured squares and rectangles.

With the benefit of hindsight and the mighty examples of postwar modernism, it’s easy for contemporary viewers to see abstraction as something obvious, a historical inevitability, and to praise figures such as Klee’s friend Wassily Kandinsky, the artist usually labelled the first abstractionist, as necessary pioneers in the manner of Darwin or Freud. But the idiosyncratic Klee, who moved both joyfully and systematically between representational and non-objective art his entire career, offers a less linear and less deterministic view of art’s progress, revealing abstraction as something that was neither inevitable nor easy – and always deeply allied to the artistic concerns of representation.

Klee offers a less linear and less deterministic view of art’s progress, revealing abstraction as something that was neither inevitable nor easy – and always deeply allied to the artistic concerns of representation.The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Klee is an artist’s artist, master of line and lover of colour. He was a consummate draftsman: This exhibition, which National Gallery curator Anabelle Kienle Ponka has assembled into a good approximation of a retrospective from the Met’s Berggruen Collection, includes one teenage drawing, a miniscule city scene of painfully accurate detail.

As a mature artist, Klee applied that superb technical skill to emotional effect whether in his comic mode – there are drawings of animals here that he created for a goddaughter – or his mysterious: He returned several times to Episode at Kairouan, an unsettling view of spindly figures, one of them apparently a camel, walking in the Tunisian desert. Klee is often quoted as saying that a line is just a dot that went for a walk; the motto is actually a paraphrase from a longer thought, but if it stuck, it’s because it captures both his virtuosity and his whimsy.

Those spidery drawings, including the intriguing patterns of Drawing Knotted in the Manner of a Net or The Perspective Spook, showing a figure lying on a gurney, both from 1920, represent one aspect of his talent. The other, of course, is the remarkable play with colour in his paintings, especially to create pictorial space. Working with colour theory during his years teaching at the influential Bauhaus school in the 1920s, he creates Static-Dynamic Intensification, a series of rectangles that begins as brown at the edges and moves to bright colours at the centre. The little oil and gouache painting looks like a stained glass window, and creates a push-pull effect that the viewer inevitably reads as three-dimensional.

Klee's Postulant Angel was created the year before his death in 1940 at the age of 60.The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Black line and coloured plane, non-objective and representational, can come together in startling ways: A tapestry of human and animal faces emerges from a field of shifting colours in Strange Garden (1923), nautical machinery sits atop a yellow ground like cutlery on a tablecloth in Yellow Harbour (1921). The most impressive things here are works that can have it all ways: Clarification, which is one of the few larger scale works, is a magnificent painting from 1932 in which the background colours hover behind rows of pointillist dots, creating seductive pictorial space in the abstract realm; in Variations (Progressive Motif) of 1927 a grid of checkered and striped squares stems from Klee’s views of architecture, but goes on to foreshadow minimalism. It would make an interesting companion to that fastidious teenage cityscape at the start of the show.

The NGC’s large, white temporary exhibition galleries are not the kindest place to be showing works this small, although low lighting and softer wall colours do their best to make this an intimate encounter with Klee. And it certainly is a touching one. The artist was labelled degenerate by the Nazis in 1933 and fired from a teaching post in Dusseldorf. He retreated to safety in Switzerland, his mother’s country and the place he was born, but he was in ill health and less productive. The Berggruen Collection has little of his late work, although it does include the bedraggled and almost bestial Postulant Angel, created the year before his death in 1940 at the age of 60. It is one of the sadder works here. Klee had seen his Blaue Reiter friends killed in the First World War (while he worked on aircraft maintenance away from the front) and lived through the dark Weimar years, yet his paintings were ever playful. His unusual combination of idiosyncrasy and rigour making his a particularly affecting art, not a march toward modernism but a dance.

Paul Klee: The Berggruen Collection from the Metropolitan Museum continues at the National Gallery of Canada until March 17.

Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor