The persistent will eventually discover the truth about Sophie La Rosière.

The little-known French painter and sculptor of the early 20th century is the subject of an investigation and two-part exhibition by Toronto artist Iris Haussler now showing at the Art Gallery of York University and the Scrap Metal Gallery. Finding that second venue will take some work; it’s at the back of a yard, down an alleyway, off a small dead-end street in Toronto’s industrial west end. Once there, the successful seeker will want to admire the mute, black doors that the Toronto collectors who founded Scrap Metal originally purchased, believing them to be modernist abstractions – and watch two documentary videos that explain why La Rosière might have chosen to hide the flowery female nudes originally painted on the doors under a thick coat of encaustic.

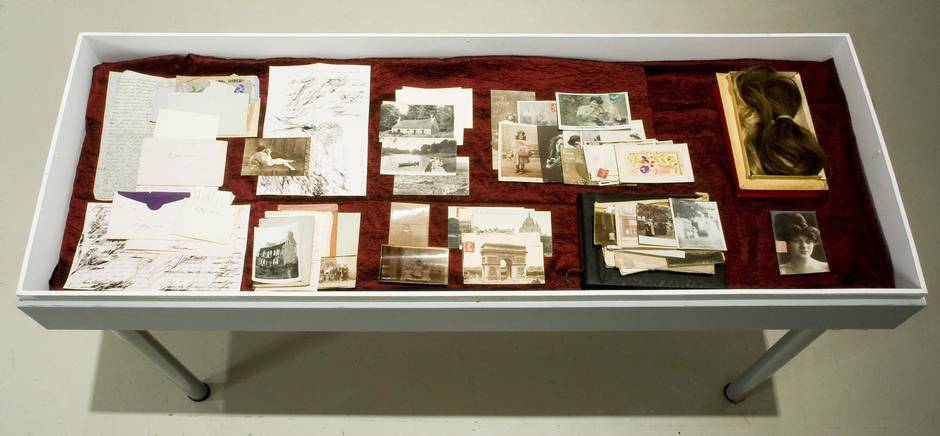

Those who then venture further, to the back of the exhibition, will eventually confront a researcher’s table covered in papers, photos and ink stamps. In the middle of this extensive jumble, there is a printed sheet of information about the mysterious Frenchwoman that begins: “Sophie La Rosière is a fictitious artist invented by Iris Haussler.”

I don’t think I am spoiling anything by revealing that La Rosière is fictional. The York University gallery newsletter calls her Haussler’s heteronym, the same person but under a different name, while her biography in the Scrap Metal catalogue is printed in grey for fact and black for fiction.

Besides, the cognoscenti already know Haussler as the artist who created the entire oeuvre of the sadly forgotten Toronto outsider artist Joseph Wagenbach and excavated the Grange to discover the odd collections of the equally fictional Toronto housemaid Mary O’Shea.

Indeed, telling you La Rosière is not a real person is a bit like handing you a novel and explaining that the characters aren’t real. Well, they are real, just not in this world.

Haussler’s projects are sometimes described as three-dimensional novels as they weave together a fictional biography with the art created by its subject. Yet that comparison might suggest that the point here is the sad narrative of La Rosiere’s life: her intense relationship with (real) artist Madeleine Smith dating back to the girls’ childhood; her disapproving parents’ decision to exile her to a convent school; her long affair with the artists’ model Florence and her heartbreak over its collapse; her final retreat to an artists’ hostel where she refused to be separated from her black-painted doors.

Certainly, the story is intriguing, full of convenient feminist themes that resonate loudly for a contemporary audience, but what is so deliciously engaging about the Sophie La Rosière Project is its playful consideration of how we enshrine both art and history.

Thanks to Haussler’s collaboration with curator and researcher Catherine Sicot, who shot videos for the project, it is full of sly contributions from various French curators, researchers and psychoanalysts delivering tantalizing insights into Sophie’s life and work. On camera, these official intellectuals tackle the mind-bending puzzle Haussler has asked them to solve with professional enthusiasm even as they implicitly satirize their own authority.

The Scrap Metal show, for example, begins with a video shot at the conservation centre for France’s national museums and featuring a long, serious explanation of the perfectly real techniques used to expose the art under the encaustic. In a second video, two psychoanalysts discuss why Sophie chose to paint over her own work – leading Scrap Metal founders Samara Walbohm and Joe Shlesinger to make the (fictional) mistake they did, valuing La Rosière for what she was hiding rather than what she might reveal.

Underneath the X-rays, and now on display in this show curated by Scrap Metal director Rui Amaral, we discover delicately drawn flowers, waves and nudes etched in series of repeating lines as though La Rosière could not bear to see the world or a body – perhaps her lover’s? – go uncharted. What is the psychoanalysis of Sophie’s game of hide and seek? She was probably suffering from heartbreak but she’s not a hysteric, the doctors pronounce; she’s an artist. The same, one supposes, could be said of Haussler.

At York, where the contemporary artist has recreated Sophie’s studio with a clutter of stained Victorian furniture, tin buckets, dirty rags and dark paintings of flowery vulvae, so convincing is the fiction that it is easy to forget that Haussler made these beautiful paintings herself. In glass exhibition tables outside that remarkable studio, pieces of debris and ephemera are on display; they include postcards and papers, and clay moulds made from life – more vulvae, now laid out in a circle like the petals of a daisy – as well as a series of stained clothes. Have those also been used to clean the studio or perhaps they are another kind of rag, left over from the fictional Sophie’s menstrual period? Whatever their fleeting purpose, they are now raised toward the level of the artistic and the eternal, mummified in the glass case as Haussler considers the way that time turns detritus into history.

At the back of this show, curated for York by gallery director Philip Monk, there is yet another video, this one shot in a French flea market: Perhaps this is where Haussler acquired the knick-knacks used to fill Sophie’s studio. Here, however, the countless, ceaseless objects of forgotten domestic lives are not elevated as art but rather laid out as wares, sprawling all over tables and spilling onto sidewalks. By collecting these once-prized leavings, associating them with a mysterious creator and assembling them into an exhibition, Haussler cleverly reproduces nostalgia – which is, of course, regret for a past that didn’t actually exist – all the while charting the progress of any object from treasure to junk to document.

The effect is compelling, leaving the viewer to reconsider the objects in the studio. Is the dirty rag of a fictional person more important than that of a real one because of its indirect association with the creative act? The studio is like some thinking person’s version of those museum dioramas devoted to pioneer life or those commercial exhibitions of props from the Star Wars or Harry Potter movies: Once you know Sophie is a fiction, you must ponder how and why you value what you see.

And so, as the intriguing Sophie is poked and prodded, she becomes paradoxically less real, more important as art than as life in a pair of exhibitions that provocatively dispute her truth even as they reinforce it.

In short, if Sophie La Rosière did not exist, somebody would have had to invent her.

Iris Haussler: The Sophie La Rosière Project continues in Toronto at the Art Gallery of York University to Dec. 11 (theagyuisoutthere.org) and at Scrap Metal, 11 Dublin St., Unit E, to Dec. 17 (scrapmetalgallery.com). Sophie La Rosière will have her own (first ever) solo exhibition at the Daniel Faria Gallery in spring, 2017.