Hardly a household name in this country, the U.S. painter Mark Tobey did his part for Canada. His connection with Emily Carr in the 1920s helped shape her career at a crucial point in her development. With this intersection, Tobey has become part of the story of Canadian art.

But he has a remarkable story of his own.

Tobey’s art – like Carr’s, tied very much to the Pacific Northwest and the region’s First Nations – is explored in a new show at the Seattle Art Museum. Modernism in the Pacific Northwest: The Mythic and the Mystical examines the careers of Tobey and his contemporaries Morris Graves, Kenneth Callahan and Guy Anderson.

“He changed the course of modern art in the Pacific Northwest,” says Patricia Junker, curator of American art at the Seattle Art Museum, which has a large collection of his work.

Tobey was born in Wisconsin in 1890. His only formal training came from the Art Institute of Chicago – part-time classes when he was a teenager. He moved to Seattle in 1922; two years later Carr was in Seattle for the Artists of the Pacific Northwest show, where Tobey also exhibited. In 1928, he travelled to Victoria to teach a course at Carr’s studio.

“In the wake of her study with Tobey … Carr produced an exceptional group of charcoal drawings that are among the most challenging and interesting works of her career,” writes Ian Thom in his introduction to Emily Carr: Collected. Thom, who is the senior curator-historical at the Vancouver Art Gallery, writes that the workshop with Tobey “expanded her artistic horizons,” as Tobey encouraged her to revisit the basics of her art, concentrating on drawing and form. The charcoal drawings “form the foundation for her later forest paintings,” Thom told The Globe and Mail.

After working with Tobey, Carr began exploring the relationship between the natural environment and totemic forms, according to the VAG, and her trees became more stylized, no longer decorative background figures.

They continued a correspondence. In her journal, Carr wrote of Tobey’s instructions: to “pep my work up and get off the monotone, even exaggerate light and shade.” In this 1930 entry, she is at once impressed with Tobey and critical. “He is clever but his work has no soul.”

She had a point. It would be more than a decade before Tobey found his artistic groove.

“He was someone who really I think did not find himself until actually the early 1940s,” says Junker. Before that, “he was truly all over the map.”

Geographically, too. He returned to Seattle at the beginning of 1939 after extensive travels abroad – to Mexico, Europe and Asia. Back on the northwest coast, his practice began to take an exciting direction.

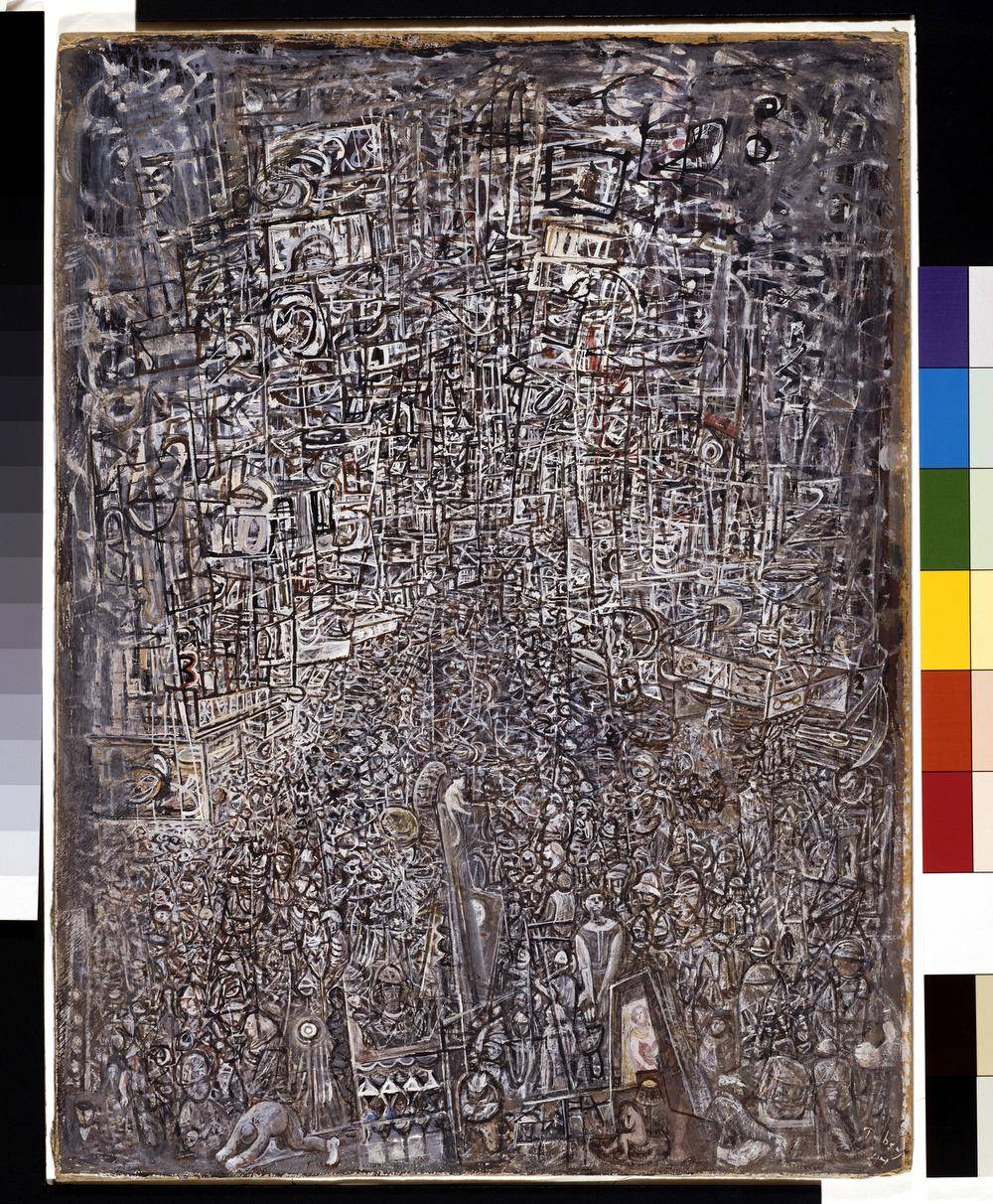

Pulling from Asian art, his own spirituality (he had converted to the Baha’i faith) and the First Nations art of the region, Tobey created an abstraction based on calligraphy, an aesthetic deeply influenced by the emblematic forms so important in Asian and First Nations art. These works – white linear gestural strokes set against a dark ground – would come to be called “white writing.”

Tobey shared his approach with his close group of peers, who were primed for a new direction, with war and the march of fascism across Europe.

“They consciously said: ‘If this is Europe’s values, why are we even looking there for aesthetic models?’” says Junker. “So they turned their back on Europe archetypes for political reasons. They also did it because they said it’s been done, it’s not necessarily relevant to us, and it doesn’t address the spiritual issues of our day.”

Carr’s First Nations influences – which manifested in a much different way – had developed long before Tobey entered her life. But Junker has seen no evidence that Carr’s interest influenced Tobey’s practice.

“I’m sure he recognized the brilliance of that. It must have stayed with him, that she was doing something distinct. But he doesn’t really channel it in that period of time. For him it comes so much later.”

It was another artistic relationship with a woman – Seattle schoolteacher-turned-New York-art-scene-figure Elizabeth Bayley Willis – that changed everything for Tobey. She took classes at his studio, and they developed a close friendship. Desperate for recognition in the centre of the American art universe, Tobey sent her to New York with instructions to get a job at a gallery and get him a show.

She became much more than an advocate. After securing a show for him at the important Willard Gallery, she identified his white writing pieces as his signature style, essentially creating the oeuvre that would define him, as well as the 1944 smash show that would announce him.

“She shaped it, she coined the term, she was the front person who spoke to the critics, and she made him famous with his first white writing abstractions in New York in 1944,” says Junker, “and the rest is history.”

With the SAM show, Junker, who moved to Seattle in 2004, wanted to emphasize the importance of this group, and encourage a definition of U.S. abstraction that is not so narrowly defined. “I have for a long time wanted to challenge this notion that there was this one modern art, and it all started in France, and then it came to New York and everyone who painted like cubism was modern and everyone who didn’t wasn’t.”

The Pacific Northwest was a vital artistic environment, its artists, liberated from the forces at play in New York, creating distinct and original modern art, says Junker. For too long they have been given short shrift in the narrative of modern art in America.

“I get a little tired of people who talk about it as the rain and fog school, as though it came only out of some external experience in the Pacific Northwest,” says Junker. “It came out of war and man’s inhumanity to man. That’s what brought this art out.”

Modernism in the Pacific Northwest is at the Seattle Art Museum until Sept 7.