If his work looks like your dusty Yes album jackets or the cover art of those Arthur C. Clarkes you toss aside in the used-book bin, it's for good reason; like them, artist Tristram Lansdowne is deeply concerned about the future.

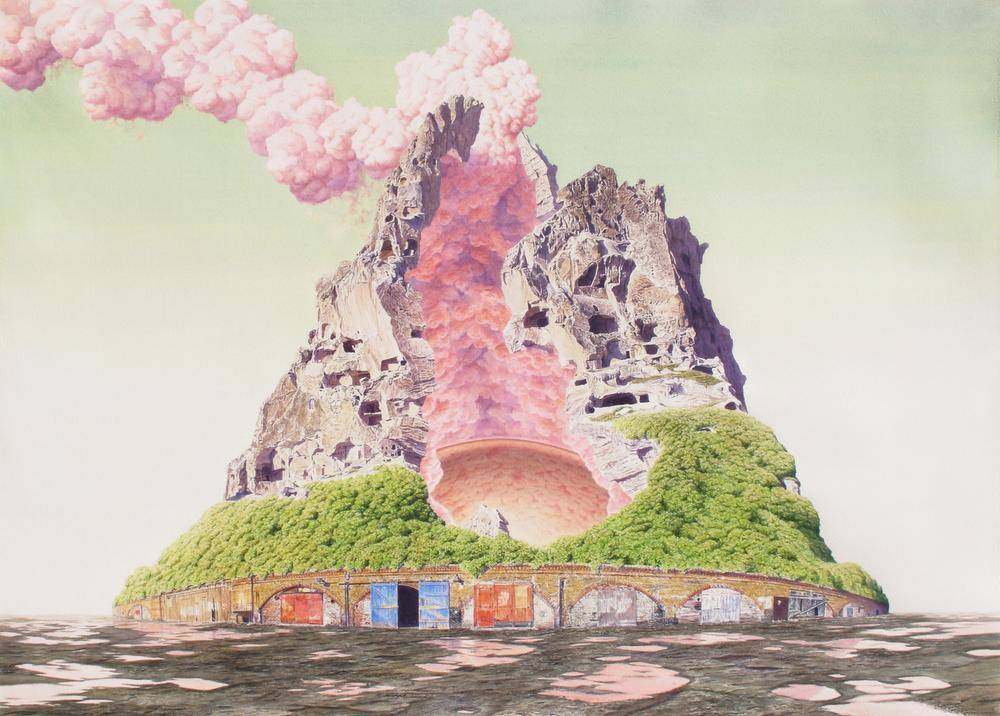

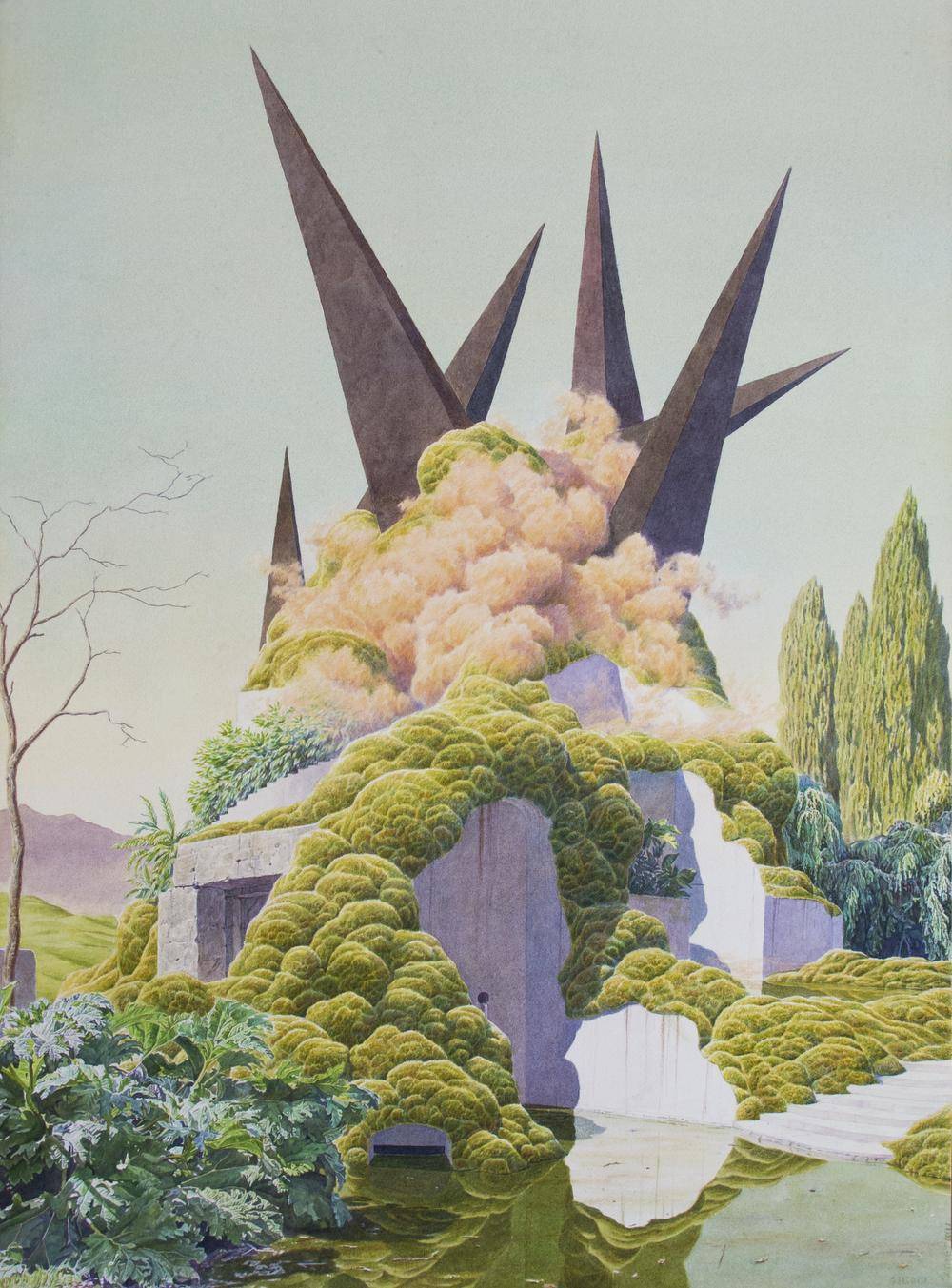

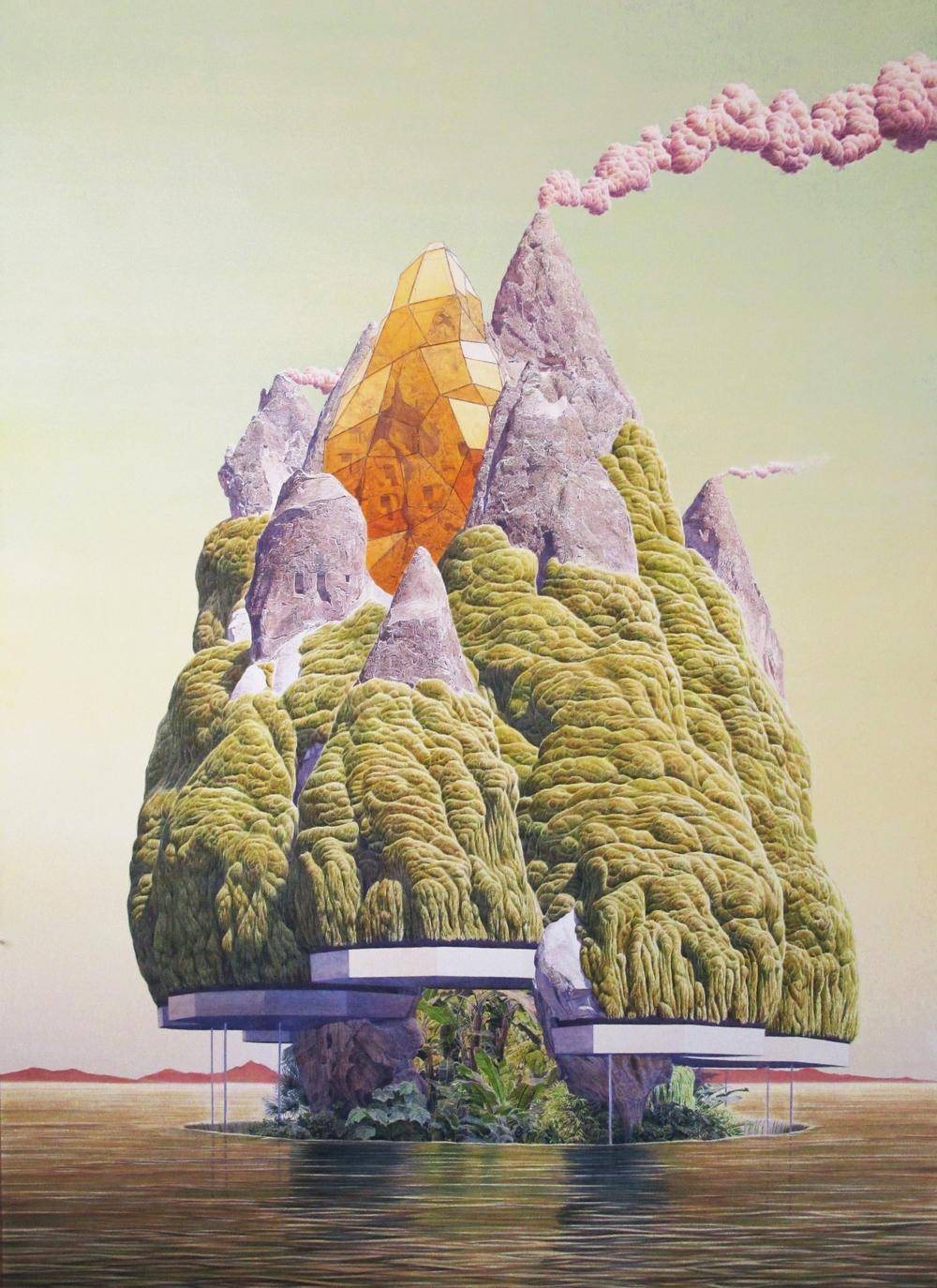

In his paintings, citrine glass biodomes are nestled among mountain peaks, volcanoes belch lavender plumes, and tidy concrete platforms negotiate cliff faces in as surefooted a way as Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater. His island landscapes are sanctuary to whole phyla of the plant kingdom – ferns, palms and mosses of every description. But there isn't a person in sight.

The Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery is offering a closer look at Lansdowne’s peculiar utopias with Provisional Futures – the 30-year-old Canadian watercolourist’s largest solo exhibition to date, which opened March 21.

When population overgrowth, climate change and rapidly depleting energy resources have become crises so massive and imminent that we can seemingly do nothing but throw our arms in the air, Lansdowne’s work plumbs the chestnuts of modernist architecture to imagine how humans and nature might live together in a more sustainable, symbiotic way.

Lansdowne, the son of acclaimed natural-history painter Fenwick Lansdowne (considered Audubon’s successor by many), grew up a block away from the ocean in Victoria. He began painting watercolour plein air while still in high school and he’d spend weekends trolling country roads with his father, documenting birds. He’d always been interested in landscapes, but he had no experience with cities.

When he moved from the University of Victoria to OCAD in Toronto to finish his undergraduate art studies, the shift was jarring. He was accustomed to mountains and ocean vistas. High-rises were disorienting, but the dissonance activated a curiosity in his art practice. He began imagining, sometimes quite fantastically, the Byzantine undergrounds and infrastructures commanded by the city’s skyscrapers.

“I started with urban architecture as a point of mystery,” Lansdowne says, “and it developed into using urban architecture as a vehicle to explore other ideas from art history and architectural history, and then those ideas became more important themselves.”

Without leaving his interest in how space is organized, his depictions of real-world urban architecture gave way to the floating islands that have become Lansdowne’s hallmark. He understands his utopias as “self-sufficient energy systems” – there’s a power source and elements of growth and decay. They are autonomous, isolated places.

“I’m sort of the 10-millionth person to realize that there’s a huge history of utopian literature, and narrative literature in general,” Lansdowne says “that’s set on an island, because it’s a convenient narrative device – it’s contained.” It’s this closed environment, he says, where you can set up a batch of variables and allow them to play out, which is kind of the utopian premise.

His Weather Station pictures a glass terradome seated atop the Technicolor-finned Kaleidoscope building from Expo 67, antennas jutting like slender birch trunks from the surrounding stone banks.

The Destroyer (Homage to Bruno Taut), the show’s centrepiece, riffs on the titular German modernist’s short-lived Glass Pavilion in Cologne, which sought to inspire morale by borrowing from the tradition of stained glass and the language of the cathedral.

Autonecropolitain I’s name suggests that Lansdowne hopes to power this island on the fuel of dead bodies – a marriage of funerary architecture and the more utilitarian axioms of utopic architecture.

Ultra-High Island spoofs 17th-century German-Italian polymath Athanasius Kircher, who within his groundbreaking geology scholarship once proposed that because of gravity, mountain springs must be continually replenished from some source, likely an underground pump system fed by the ocean’s whirlpools. Lansdowne adds a little stoner barb to the joke, adding a portal to outer space in the centre of the geodesic mossy structure, “in case it needs more suction.” There’s an internal logic to Lansdowne’s work – sometimes it crackles with hope; sometimes, it underscores folly.

Thinking on his dedication to landscape painting, Lansdowne offers that from his childhood home he could see the Trial Islands – an uninhabited ecological reserve less than a kilometre from the shores of Victoria’s Oak Bay.

There are endangered plants that grow on those islands, ones lost elsewhere in British Columbia, because people just don’t go there. He canoed there once, but the riptides have killed other adventurers.

“I walked my dog past that landscape every day,” Lansdowne says, “It’s one of the most prevalent scenes in my life.” He wonders: Maybe he’s just painting the Trial Islands over and over. Like his utopias, they, too, exist in an incredibly delicate balance.

Tristram Lansdowne’s Provisional Futures is at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery in Kitchener, Ont., until April 27 (kwag.ca).