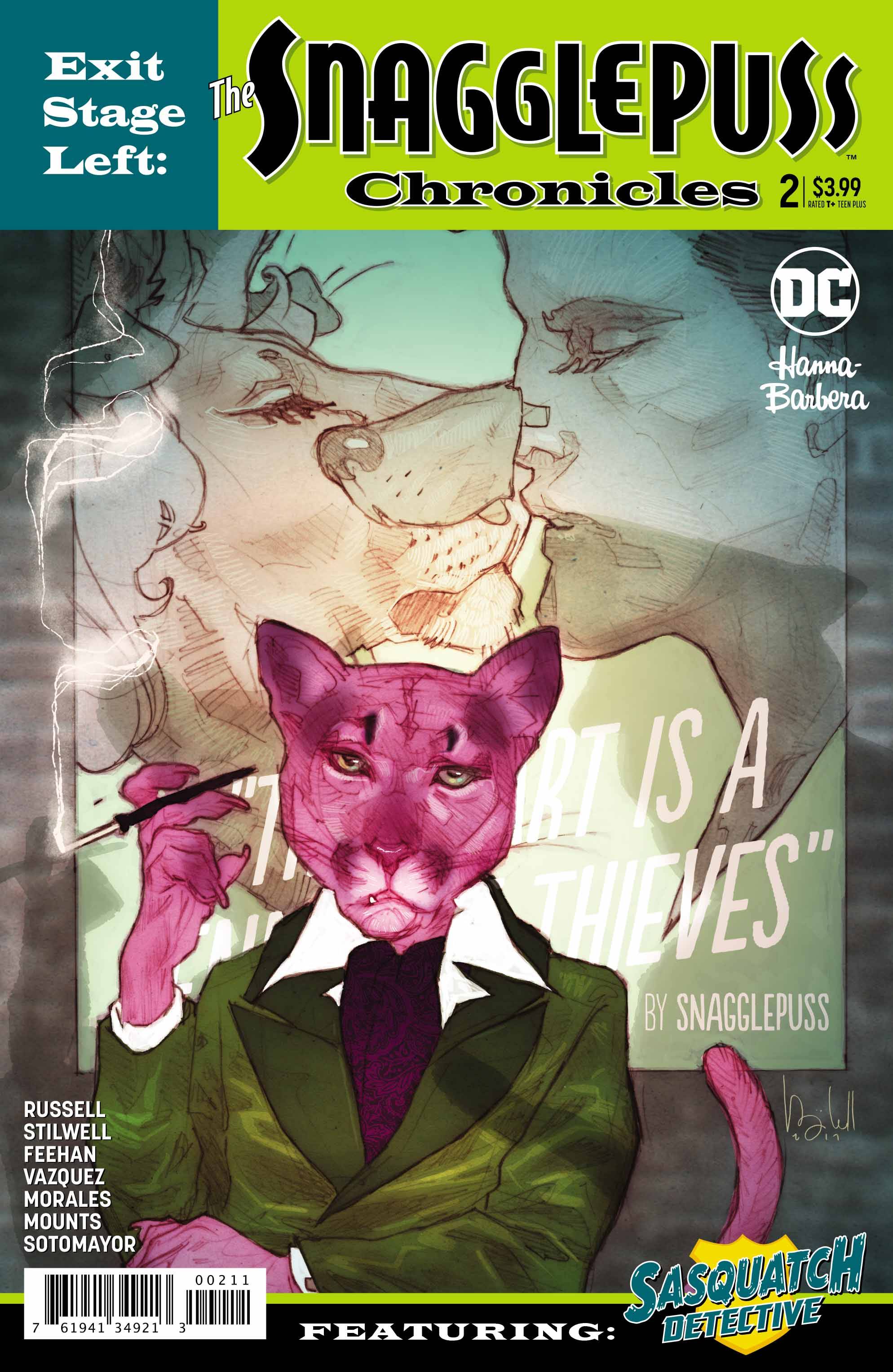

Remember Snagglepuss? Hanna-Barbera's anthropomorphic pink cartoon lion from the early sixties? "Heavens to Murgatroyd"? That incongruous set of cuffs and a collar over his fur? Those groan-worthy puns, that sardonic drawl? He's now the star of a new 1950s-set comic-book series, Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles, which debuted in early January.

Midway through the first issue, the corpse of a gay Cuban man, beaten to death by dictator Fulgencio Batista's police, floats face down in a pool of bloody water. Later, eager onlookers witness Ethel Rosenberg's execution as she pleads for her life in the electric chair. By the end of this first chapter, the House Un-American Activities Committee is preparing to persecute Snagglepuss for his communist leanings – and his soirées spent canoodling in the Village, at the Stonewall Inn.

Yes, in the hands of writer Mark Russell and Newfoundland artist Mike Feehan, Snagglepuss has been reimagined as a closeted, Tennessee Williams-esque playwright in 1953 Manhattan. No longer a simple cartoon, our hero is now a realistically drawn, sad-eyed, bipedal pink cat in a world of red-baiting humans. And no, this is not a joke. But who in the world asked for serious Snagglepuss?

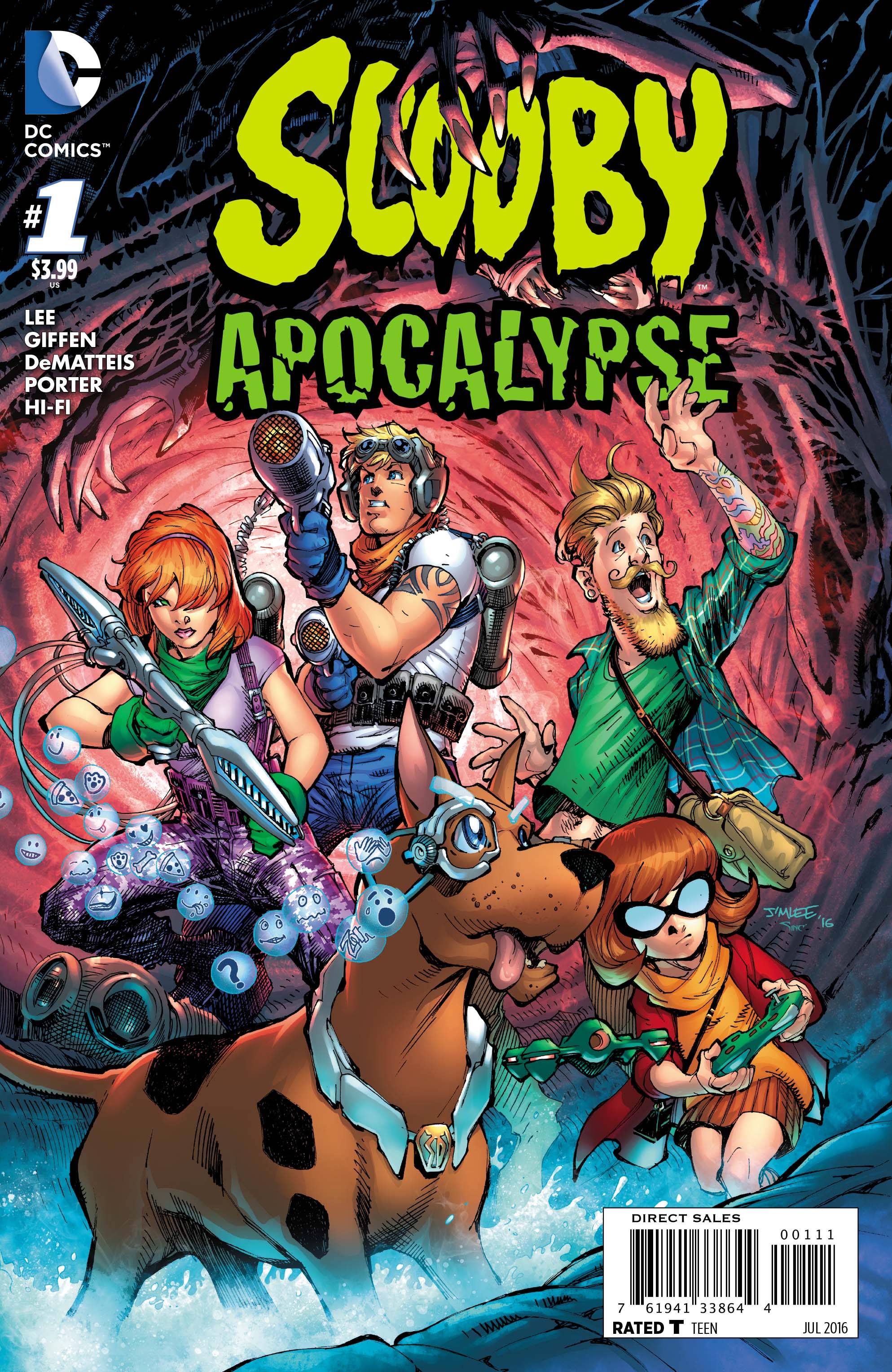

"These are not your parents' comics," the ad copy boasted when DC Comics rebooted their Hanna-Barbera properties in the summer of 2016 under the banner of Hanna-Barbera Beyond. They're certainly not your children's comics, either. Frankly, it's not clear whom they are for.

In Scooby Apocalypse, Scooby and the gang star in a Walking Dead riff, combating mutants in a postapocalyptic dystopia. Everyone is a millennial, now: Scooby speaks in emojis; Shaggy has sick tats and sculpted facial hair. In issue 17, we are vouchsafed a glimpse of Fred and Daphne naked in bed together. At long last!

In the 2016 Hanna-Barbera Beyond reboot Wacky Raceland, the Wacky Racers star in a Mad Max riff, competing in mutated hot rods in another postapocalyptic dystopia. Everyone is grizzled now: Lazy Luke is an alcoholic; Penelope Pitstop kicks butt while wearing a form-fitting pink jumpsuit. Mean Machine provides a typical line of dialogue: "I sure as hell don't have to take crap from a damn eight-legged lizard." Talk about wacky!

And then there's The Flintstones, the crown jewel of Hanna-Barbera Beyond. Lauded by critics for being "invitingly biting" (Washington Post) and "one of the sharpest social satires around, in and out of comics" (the Hollywood Reporter), The Flintstones, like Exit Stage Left, is written by Mark Russell. Both of his series share similar approaches to "biting" "social satire."

As with Snagglepuss's realist makeover, the modern stone-age family has been bulked up well beyond their flat cartoon origins. The Flintstones now have muscle mass! Wilma and Betty are pin-up pretty, while Fred and Barney's caveman flab has hardened into the thewy pecs and quads of your typical superhero. What's more, just like Snagglepuss, the Flintstones now have psychological depth. Fred and Barney are troubled war vets who admit to having carried out genocide on the "tree people" in a massacre staged as a kind of paleolithic My Lai. And that's just for starters.

There is a tendency, in recent decades, for forcing icons of kids' entertainment to "grow up" by subjecting them to hardcore, soul-rattling trauma, as though that can render them cultural objects that adults need not feel guilty for consuming. Anne of Green Gables is dark and troubled. Archie and Jughead are grim and gritty. Superman kills people. This stuff is not just for kids anymore!

In keeping with this trend, why should Hanna-Barbera Beyond stop with Snagglepuss falling victim to the "lavender scare" or Fred Flintstone wrestling with post-traumatic stress disorder? Perhaps future storylines could feature Huckleberry Hound flashing back to his childhood escape from a puppy mill, Jabberjaw the shark waking up in SeaWorld, or Captain Caveman trying to kick an opioid addiction?

Fond nostalgics and entitled fans might bray about Hanna-Barbera Beyond betraying the brand, but it's far more objectionable that these characters are so incommensurate to the subjects they address. Both Exit Stage Left and The Flintstones leverage the same tired gimmick – what if make-believe character X had to deal with real-life social problem Y? – in a bizarre attempt to thrust maturity onto concepts that are inherently silly. These comic books catastrophically misjudge how much allegorical weight such flimsy characters can shoulder.

That very flimsiness, that obvious lack of complexity, was part of the charm of the original Hanna-Barbera properties (think of Fred driving past the same stone-age bungalow over and over again). A previous reboot of some of the company's characters worked precisely because it embraced how thin, repetitive, and simple those initial cartoons had been.

In the mid-nineties, the Cartoon Network scored a series of successes starting with Space Ghost Coast to Coast – a late-night talk show "hosted" by Hanna-Barbera's intergalactic superhero – because the programs acknowledged that the studio's signature stiff animation and boilerplate concepts were ludicrously inadequate to the task of reckoning with contemporary life and sensibilities.

DC's reboot, on the other hand, ignores the characters' simplicity in favour of a spurious and unearned complexity. It's no stretch to view a pantsless, campy pink cat from Saturday morning TV as a kind of gay icon. But to think him a fit vehicle to discuss Stonewall, oppression, and murderous hate crimes, does not just do a disservice to Stonewall, it does a disservice to Snagglepuss. The result here isn't grown-up social satire. It's kitsch.