In Judy Blume's 1970 young adult novel Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret., the protagonist Margaret Simon, on a personal spiritual quest, attends a Rosh Hashanah service at a synagogue. Reading Blume's novels as a teen, Toronto writer S.K. Ali, the Muslim daughter of South Indian immigrants, marvelled at how these religious spaces – ones she'd never set foot in – were seamlessly integrated into the characters' worlds without any fuss. But a question tugged at her: "What was the difference between that and having a Muslim girl go to mosque?"

It took three decades for Ali, now a 45-year-old teacher, to see a YA novel with a Muslim protagonist as relatable as the ones in Blume's books – and she was the one who had to write it.

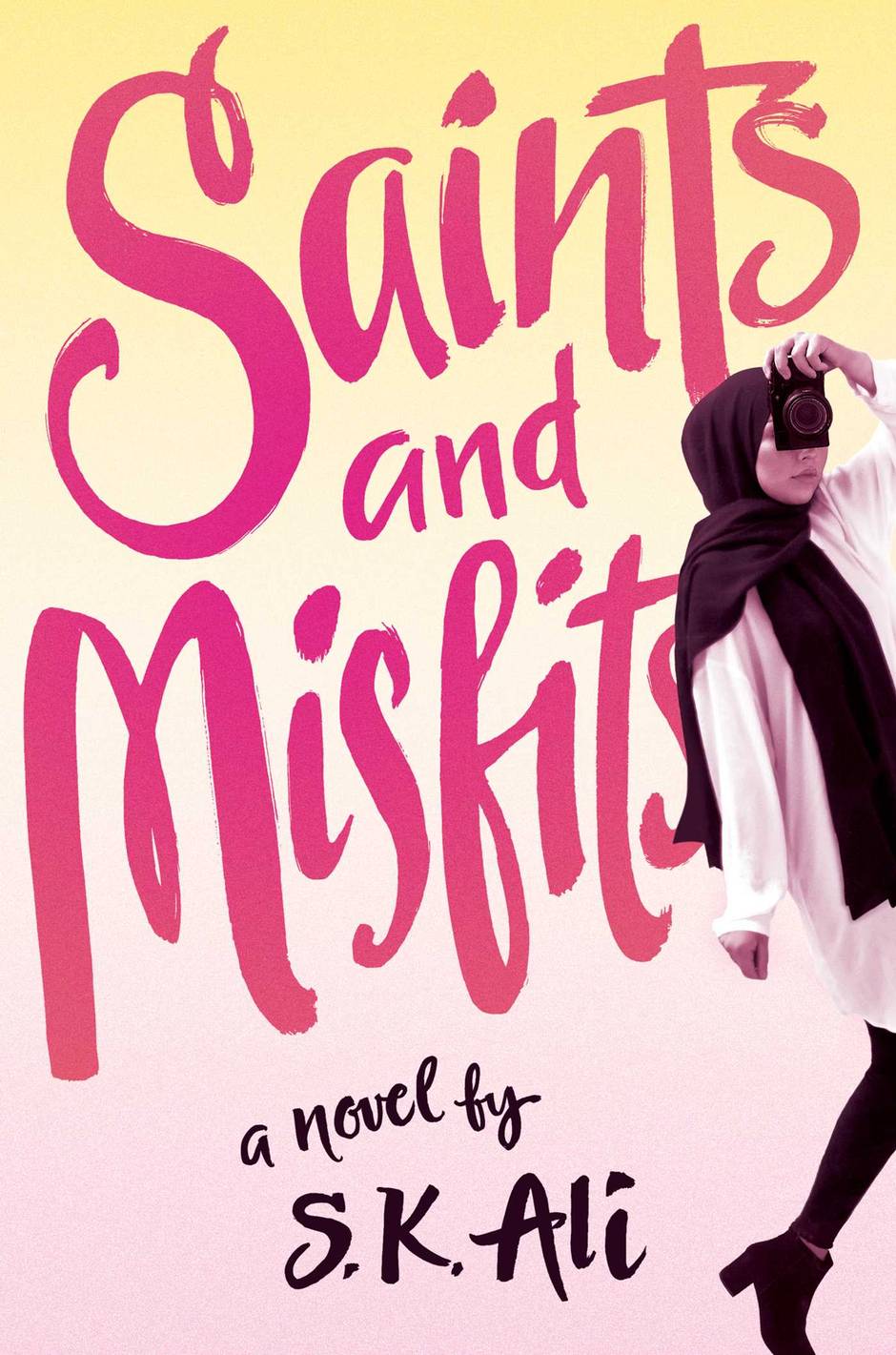

Her debut novel,

Saints and Misfits, told from the perspective of 15-year-old Janna Yusuf, was published in June by the new Muslim-focused Simon & Schuster imprint Salaam Reads.

It comes at a time when the publishing industry is making notable efforts to recruit underrepresented writers to tell stories starring underrepresented characters. This long-overdue shift is largely motivated by the #weneeddiversebooks movement, which was started on Twitter in 2014 to draw attention to the lack of diversity in children's literature.

The statistics are striking: In a 2014 analysis of 3,500 children's books published in the United States and Canada, just 11 per cent were about non-white characters and only 8 per cent were written by non-white authors, according to the Cooperative Children's Book Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Until recently, most so-called diverse offerings were didactic explainers of non-Christian holidays or what LGBTQ publisher S. Bear Bergman sneeringly calls "very special episode" stories, in which plots can be summed up as "some people have two moms … and that's okay" or "some people use a wheelchair … and that's okay."

That's not the kind of story Ali wanted to write about a Muslim girl growing up in the United States. In fact, the central plot points of Saints and Misfits don't veer all that much from standard YA fare: Janna likes to dress in all black, she's an amateur photographer who surreptitiously takes photos of her crush, she has a fraught relationship with her mother. She wears a hijab and even briefly a niqab – the latter as an empowering suit of armour in the novel's climax rather than as a garment of oppression. Ali wrote Janna as a complex, three-dimensional character whose religion does not define her.

"Judy Blume's characters were not exoticized," Ali says. "They were part of the American fabric, and that's what we are, too."

Ali says she wanted the protagonist of her book, Saints and Misfits, to be a relatable, realistic teenage protagonist – who just happens to be Muslim as well.

Galit Rodan/The Globe and Mail

It's her belief, and that of many publishers and writers, that authenticity in depicting these characters lies in who tells the stories.

Author Jael Richardson, the founder of the Brampton-based Festival of Literary Diversity, says the industry has never taken racialized writers seriously.

"I think there has been a common perception that white writers are experts at writing and diverse authors are experts on diversity," she says.

But even the opportunities for diverse books often go to the nearest proven talent rather than someone with the experiences needed to inform the writing, says Bergman, who runs Flamingo Rampant. His press distributes its titles directly to customers in bundles of half a dozen books annually – at least half of them by authors who are black, Indigenous or people of colour.

For a forthcoming book about pow wows, the Indigenous authors provided an enormous amount of reference material for the illustrator.

"You can research on the Internet all you want, but you won't know that this thing doesn't go with that thing unless there's somebody who's lived it for 40 years to tell you," Bergman says.

When a big publishing house does take a chance on a writer of colour, that writer faces pressure to be commercially successful in a way their white counterparts do not, Richardson says.

"There's this trial effort. 'We will put you out there, we will give you this spot, and if you don't make it, that's your fault.'"

Writers who reach that stage at all are the lucky ones. Unless they're working with small publishing houses such as Bergman's, simply getting an agent to look at a manuscript can be a serious challenge for writers of colour specializing in children's literature.

That's one of the reasons Salaam Reads, Ali's publisher, takes submissions directly from writers. Zareen Jaffery, the imprint's executive editor (who is also Muslim), says this practice grew out of feedback she received from Muslim writers, who said it was difficult to find an agent. Those who did find one were often asked to make changes they were uncomfortable with, such as rewriting a brother or father character as radicalized in an attempt to make a story more recognizable to non-Muslim readers.

Similarly motivated, multidisciplinary trans artist Vivek Shraya launched VS. Books in June, an imprint of Vancouver-based Arsenal Pulp Press that will publish the works of young writers who are Indigenous, black or people of colour. A contract with VS. Books comes with mentorship from Shraya, who has published several titles with Arsenal.

In fact, Arsenal's first foray into children's literature was Shraya's

The Boy and the Bindi, richly illustrated by Rajni Perera. It's a simple story of a young boy playing with the idea of gender through wearing a bindi – an act his mother supports. At no point is the child scolded for what some might see as a transgression, a decision Shraya says was very deliberate. She was frustrated by the number of books about "different" children that followed a bullying narrative and felt a responsibility as a queer writer to imagine other possibilities.

Although they don't necessarily guarantee a spot on the bestseller list, publishers are beginning to recognize this same moral imperative to develop stories along this vein.

Initially, the majority of customers who bought books from Bergman's Flamingo Rampant were LGBTQ people. For Bergman, the goal was simple: to allow all kids to see some part of their experience reflected positively in literature.

But now he also has his eyes trained on reaching a mainstream readership, in the hope that a child reading about a character who is trans can go a long way to normalizing that identity and promoting tolerance.

"The preventive work is not when they're 25, it's when they're 5," Bergman says. "It's when we have an opportunity to show them in a chill, non-confrontational, loving way that LGBTQ people exist."

Orca Books in Victoria, a Canadian pioneer in diverse children's literature, has won numerous awards for its offerings, many of which are empathetic depictions of Indigenous children. Most recently,

My Heart Fills With Happiness, a simple meditation on what makes a First Nations girl happy (traditional dancing, freshly baked bannock) by Monique Gray Smith and Julie Flett, took home a B.C. Book Prize in May.

Some of Orca's titles, though, still feature characters who are positioned as victims of bullying because of their minority status. Ruth Linka, Orca's editorial director, says she includes these books in her catalogue because bullying is a theme readers like to see explored in literature.

"We never want to further marginalize kids who are already being attacked for race or gender identity or their parents' sexuality," she says. "But if a good story comes to us and it does have a bullying narrative, we won't turn it down."

Richardson is willing to cut publishers some slack: They're still trying to figure out which types of stories work, which are important to publish, which will sell. A step toward making better decisions in that area will take time, she says, and will rely on publishing houses hiring more diverse people in their acquisitions departments.

The work isn't finished once a book is published, though. In 2016, Richardson adapted the memoir she wrote about her relationship with her father, a black former CFL player, into a children's book called

The Stone Thrower. On a trip to a university town in Eastern Ontario, she stopped into a bookstore and offered to do a reading. The bookseller declined, explaining that the town was "very white" – a suggestion that a book featuring a black Canadian would not be of interest to anyone who was not black.

She says the solution lies in publishers putting major marketing dollars behind these titles, which will then trickle down to distributors taking them seriously.

Although Salaam Reads is openly labelled as a Muslim imprint, all its titles feature kids and young adults whose stories have a universal emotional appeal, Jaffery says. After she'd edited Ali's Saints and Misfits, she handed it off to some in-house readers, explaining that the book was like the nineties TV show My So-Called Life, about an articulate young woman at a turning point in her life – the protagonist just happened to be Muslim.

"I grew up reading books with characters who didn't look like me and in many ways weren't similar to me, but I related to them on an emotional level," Jaffery says. "That's the kind of language I use to position any of my books."