Jack Dunn spent more than 10 years researching, writing and finding photographs for his book, The North-West Mounted Police: 1873-1885.

Jack Dunn is a retired Calgary public school teacher who devoted the past decade of his life to his meticulously researched tome, The North-West Mounted Police: 1873-85. The historian's second book documents the Mounties' formative period in what Dunn considers the most historic dozen years in Western Canadian history. Dunn, who recently turned 81, lives in Calgary.

Though your book focuses specifically on the Royal North-West Mounted Police, how far does your fascination stretch back with Mounties more generally? Were you interested as a child?

I wrote a book, The Alberta Field Force of 1885, that was published about 20 years ago, so I was interested in the Mounted Police. That book was more of interest locally; I thought with this topic, there would be interest nationally.

As a child? Not really. I remember I was at a summer camp and the Mounties came out with a dog. They threw three bottle caps in a large field and the dogs went around and found the bottle caps. It kind of impressed me. That's the only contact I ever had with the Mounted Police at a younger age.

You've just written 778 pages about a 12-year period. Why are those years so fascinating?

They were the most important years in Western history. So much happened. Mounties come West, the buffalo disappear, the Canadian Indians go to Montana, there's starvation, you have the treaties, you have the railroad built. By 1885, the land is just transformed. The white population became the majority in that 12 years, from a handful of whites to the whole ethnic composition of the Prairies changed. I say it's the most momentous period in our time.

Between the diaries, letters, newspapers, official reports and the personnel files you used as resources, can you quantify how much material you studied?

Personnel files? Nine hundred of them. Some of them were 200 pages long, some were two pages. You never know what you're going to get. I don't think anyone's ever gone through them like I have. It took me 10 years, the diaries. Quite a few of them are in Montana because the desertion rate was so high. From the personnel files and primary sources, you get your main information.

What scenes amid many did you find particularly grim?

It was a rough life. You can imagine travelling to Calgary to Fort Macleod in January in 30 below weather. Some of them would ride 4,000 kilometres in a year. Tremendous distance. What do you do when a hailstorm comes? If they could find a badger hole, they'd bury their head in it to prevent the hail from hitting them. It was a rough world.

Speaking of horses – and given the fact that your author photo does include a cowboy hat – do you have any riding experience?

Yeah, a little bit. I won a horse at Kids Day at the Stampede [almost 70 years ago]. I'd never ridden a horse. It was a Dartmoor, and that's half-Shetland, half-horse, but it doesn't have the mean disposition of a Shetland – they're so mean. That horse, he would bow and shake hands with you. He was well-trained. But I had to get rid of him because I had nowhere to look after him. I kept him for the summer, rode him every day and then traded him for two CCM bicycles.

There's 20,000 kids at Kids Day and I won a horse. That cost me thousands because I buy lottery tickets all the time. I'm expecting to win again, but no such luck.

You organized the editing, design, photos and publication for this book. How?

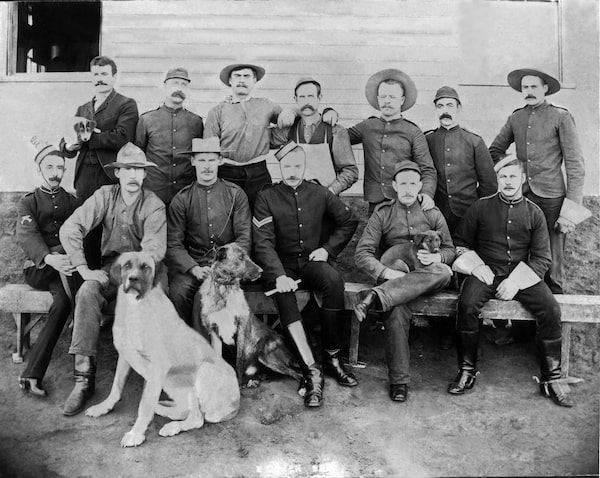

I did the whole thing myself. I was going to get government support and I decided, nah, I'll do the whole thing myself. So when I wrote the book of course I got an enormous amount of data; about 50 bound volumes of diaries and newspaper accounts. Then when it came time to publish, I was going to look around for a publisher, but I thought, no, I'll do it myself. It meant I had to put up all the costs. For the photos – I think they're exceptional – I collected the photos. I got about 24 that were never published. I got one from a farmer at a gun show. You never know where you're going to find something.

I know you've played hockey, hiked and snowshoed in the past – at 81, have you had to give anything up?

I quit hockey four years ago. I skate recreationally three times a week for exercise. I enjoyed hockey for a long time. It gets to the point where you can't keep up with them. Some of them (in my league) played junior hockey. You're a pylon out there.

Snowshoeing, we're always going on Mondays with another couple. And we go hiking in the mountains. We picked Monday because the weekend is over and no one is around. Sometimes you won't see anyone all day. Calgary's good; 700 kilometres of bike paths. I do that in the summer. I have a truck and a bicycle, and that's my main recreational activity.

Michael Redhill has won the $100,000 Scotiabank Giller Prize for his novel 'Bellevue Square,' about a woman on the hunt for her doppelganger. The Toronto author says it would have been foolish to imagine he could win the award.

The Canadian Press