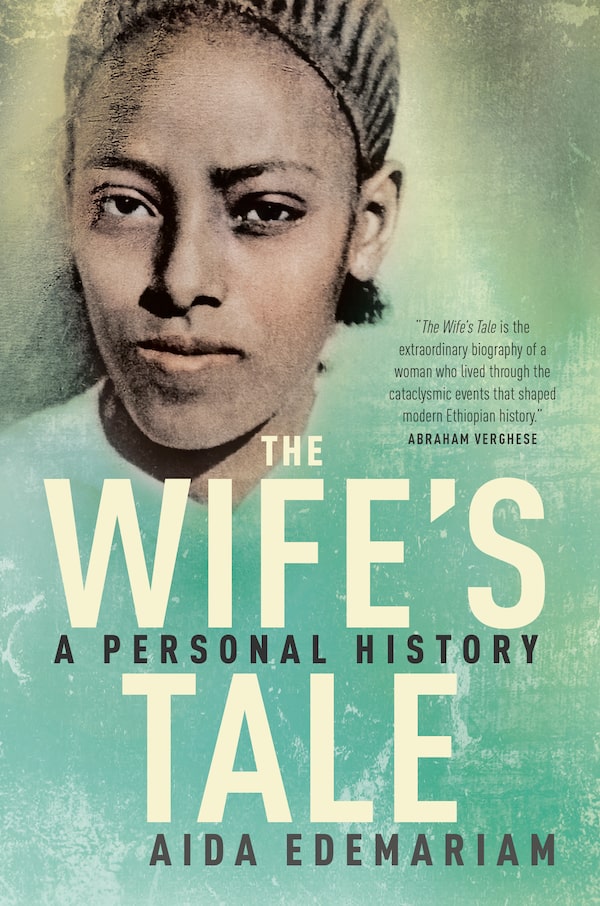

Aida Edemariam.

“I love listening to her.”

For many years, on and off, Ethiopian-Canadian journalist Aida Edemariam would record the incredible stories told by her grandmother, Yetemegnu, whose life in Ethiopia covered nearly a century in which she saw – against a personal backdrop of parenthood, widowhood and political strife – a country transformed by invasion, occupation, revolution and civil war. Edemariam would put together a book proposal in the early part of this decade. The result of years of transcribing, researching and transcribing again, is The Wife’s Tale (Knopf Canada), a book lovingly and deeply imbued with Yetemegnu’s voice. Now based in Britain, Edemariam recently spoke to The Globe and Mail on a visit to Toronto.

All in all, how long was the translation process for the book?

Very time consuming. I had about 50 to 60 hours of tape in Amharic. I spent an amazing amount of time with the Amharic dictionary. I speak Amharic, but she spoke a very rich Amharic. There were many proverbs and references to church. It took about a year. There was a lot I knew, or thought I knew, because I lived there, but she lived in a different time. She was born a century ago and there was huge change in that century. So I had to get a sense of that, and once I had done that, I then went back and listened to all of it and translated all of it again. And I heard loads of resonances and dissonances the second time around. But yes, it was quite detailed and time consuming.

Why did you choose to tell your grandmother’s story as a memoir?

I didn’t really think of it as a memoir when I wrote it, I thought of it as a biography. You may or may not think there’s a difference there, but in some sense, there is a little bit of distance in the story. Because really, it’s not about me. I do appear a couple of times but it’s basically about her and I’ve very deliberately taken myself out of it. … Are you asking why I didn’t write a fiction?

Not a fiction. But you’ve crafted an incredible literary tale, where someone else might have taken a more literal approach to a family history.

I mean, it’s a very literary place, you know. She didn’t read or write, and didn’t read until she was in her 60s. But it’s a very literary place. Her husband was a priest and poet. It’s a place where your skill with language is prized, your skill with pun and hidden meaning is prized over making jewellery or singing.

But I couldn’t write a standard biography because I didn’t know half the dates. I could have literally spent decades chasing dates and I thought that was a waste of time. So you kind of become led by story and led by the cycle of the seasons and the cycle of religious festivals and the life cycle of Mary, the young girl who married an older man. When you think in those terms, you can use those resonances and just set them going and they give a richness to what you’ve written.

I don’t mean this to sound so blunt, but what’s so important about one’s own family’s story?

One thing is: Why not? And two: History is lived by ordinary people in just as much vividness and sometimes more, particularly in times of turmoil than it is by the great supposed main actors in it. I spoke to Edmund de Waal about writing a family memoir, and he mentioned a lot of things that went through my mind. Because, yes, “Who cares?” But if you pay enough attention to the particularities, then you can make somebody live on the page. He said it’s almost a test of writing if you can take somebody that nobody knows about and make the reader care.

The sure answer is there’s no particular reason for people to care, but hopefully I’ve persuaded them to care.

Since you’ve been promoting the book, do you find people are knowledgeable about Ethiopian history and culture?

No! (Laughs.) In England, people tend to think about the 1980s summit and Bob Geldof. And I’m very keen that that is not the only way in which Ethiopia is seen. Even the assumption of famine and dryness – the back of my English edition has an incredibly green landscape, the country was agriculturally very rich. But I didn’t write a guidebook. All of that stuff is important but in some way incidental as well.

The audiobook version must be rich in details from your tapes.

It was beautifully recorded by an actor named Adjoa Andoh. We spent a lot of time in the recording studio working out Amharic words – I didn’t quite realize how many there were in it. And I provided clips of my grandmother singing and talking. It was very cool, and also strange, to listen to a story that has long been in your head, in a different language and to hear a brilliant actor read it with an amazing voice.

I read recently about your father’s passing. My condolences. I get the sense that he was a great help in bringing the book together.

Yes, that makes it difficult to launch this because he was such a part of producing it. My father and some of her other children, but especially my father, was there for some of the interviewing. And he was there for some of the stories when he was a child, so he often thought of asking things that wouldn’t occur to me. He shared his memories and he was incredibly patient. He never complained. He came with me on some trips and it’s not necessarily straightforward to organize a horseback trip in the middle of his mother’s funeral, which was beyond the call of duty. He was incredibly supportive. All of my family were.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Cliff Lee

Cliff Lee