Canada finally banned asbestos at the end of last year, after years of public pressure – but the legacy of mining, using and exporting the deadly mineral lives on, in this country and around the world. In his book A Field Guide to Asbestos (Yoffy Press, 72 pages), award-winning photographer Louie Palu reveals the devastating toll this carcinogen has taken. His work – some of it as a former Globe and Mail staff photographer – is based on 15 years of focus on these oft-underreported stories. It covers the vast mines in Quebec to industrial sites in the United States and England, showing the daily struggle of cancer patients and their families in Ontario and Scotland, along with workers – toiling without any protective gear – handling asbestos products in India.

Workers outside an auto parts plant in New Delhi, India, that uses asbestos in the manufacture of car components. These workers wear no safety equipment while working and have no access to equipment to stop them from inhaling asbestos dust.Louie Palu/ZUMA Press

Asbestos, once dubbed the “miracle mineral,” was widely used for insulating pipes, in roof tiles, children’s modelling clay, talcum powder and fake snow. For decades, Canada played a central role in the mining, manufacturing and export of the mineral, even as evidence grew of its impact on human health. This country’s last mines closed in 2011, but the story is not, by any means, over. Carex Canada, a research program, estimates that about 152,000 Canadians are exposed to asbestos in their workplaces – people such as carpenters, pipefitters, construction workers, mechanics, and ship builders.

The scar on John Nolan's back from a 2014 lung removal, which followed his diagnosis with mesothelioma. Nolan, seen here at age 67, is from Stevensville, Ontario, and was exposed to asbestos during a renovation near his office in Windsor, Ontario, in the 1980s.Louie Palu/ZUMA Press

In Canada, asbestos remains the leading cause of workplace deaths in the country. Since 2000, there have been more than 7,000 new cases of mesothelioma, a painful, deadly form of cancer caused almost exclusively by asbestos exposure. The actual toll is much higher – the recent mesothelioma numbers exclude Quebec, which continues to have new cases diagnosed each year, and scores more have died from other asbestos-related diseases such as lung cancer and asbestosis.

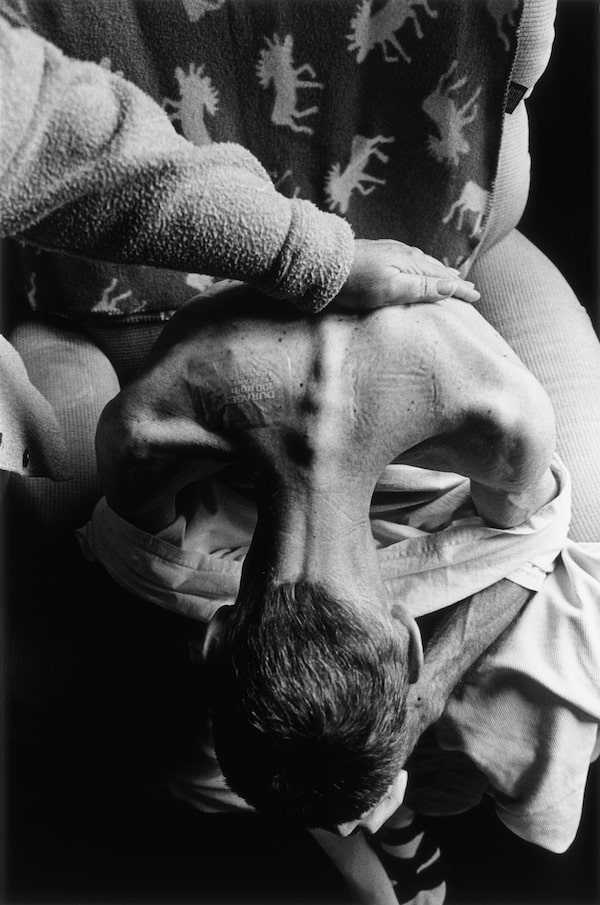

Blayne Kinart is comforted by his wife Sandy after receiving a painkiller in the form of two patches stuck to his upper back.Louie Palu/Zuma Press

Blayne Kinart was one of them. Few images are more haunting than that of the 58-year-old former millwright with mesothelioma. He stands, emaciated, silhouetted against a window in his living room in Sarnia, Ont., every bone in his torso visible, his arms like sticks. Palu documented him kissing his daughter Shari goodbye during his final days as he took painful breaths with the help of a respirator.

Blayne Kinart kisses his daughter Shari goodbye after a visit to his house in Sarnia, Ontario. Kinart was a former millwright who died from mesothelioma, a cancer in the lining of the chest wall, in 2004.Louie Palu/ZUMA Press

The images are difficult to contemplate. One 48-year-old man in Campbellford, Ont., has mesothelioma; his exposure came as a child, from his father’s work clothes; two of his siblings had already died from the same cancer. In a rural community near Ahmedabad, India, a woman and her children live in a home made from broken asbestos tiles. Canada was long a top exporter of asbestos to many developing countries such as India and Indonesia.

This woman’s house in a poor rural community on the outskirts of Ahmedabad, India, has broken asbestos roof tiles. Almost every single residence in this village – and many villages and cities like it throughout India – have asbestos cement products in them.Louie Palu/ZUMA Press

Meanwhile, the legacy of asbestos lingers – in Canadian schools, universities, government buildings and in some homes, where it was used in insulation. Removal is regulated, but breaches often occur; a do-it-yourself home renovator, a car mechanic or a janitor may also be unknowingly breathing in the dangerous dust, and the latency period for getting sick is decades. Palu cites one expert who notes that these deaths tend to happen one by one, out of sight – if they all died at once, in the thousands, the world would pay attention. The observation stuck with him. These people "suffered alone and died anonymously, and few of us hear about them,” he writes. This book acknowledges them, and shines a light on what has for long been a silent killer.

Raghunath Manwar examines an X-ray of one of several workers who has been diagnosed with asbestosis in Ahmedabad, India. Manwar is the secretary of Occupational Health and Safety Association, a non-governmental association that assists employees affected by asbestos from a power-generating company and a cement factory.Louie Palu/ZUMA Press

Tavia Grant is a reporter for The Globe and Mail. She worked with Louie Palu on a 2014 project, No Safe Use, about the health risks of asbestos.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.

Tavia Grant

Tavia Grant