For anyone with a similarly cherished Williams memory, reading Itzkoff’s new biography, simply titled Robin, will produce more than a few throat-lumps.

Like millions of moviegoers and television viewers and stand-up comedy fans and really anyone with even a tiny sliver of investment in pop culture, Dave Itzkoff has a favourite Robin Williams moment.

It was 1980, and The New York Times culture reporter was a four-year-old kid, seated for a showing of Popeye. Robert Altman’s musical-comedy was intended to launch Williams from his Mork & Mindy sitcom fame into the stratosphere of big-screen blockbusters. Instead, the movie was directed by a filmmaker more comfortable with intense human drama than singing sailor men, saddled with a script that can only be described as wildly, maniacally uneven, and entrusted with a budget that was blown long before the end of production. Yet the young Itzkoff was enthralled.

“It was such an off-the-wall film, so weird and rough around the edges, but at the same time warm and tender,” recalls Itzkoff, who saw Popeye twice in the same day, thanks to his mother’s habit of arriving to the movies 10 to 15 minutes late, then convincing the usher to let her family sit through the next showing for free. “A comic-book or cartoon adaptation would never get made like that now, which is part of the pleasure of it. And Robin gives such a terrific performance – not just the acting, but the songs, too. The lullaby he sings to Swee’Pea ... even describing it now gives me a lump in my throat.”

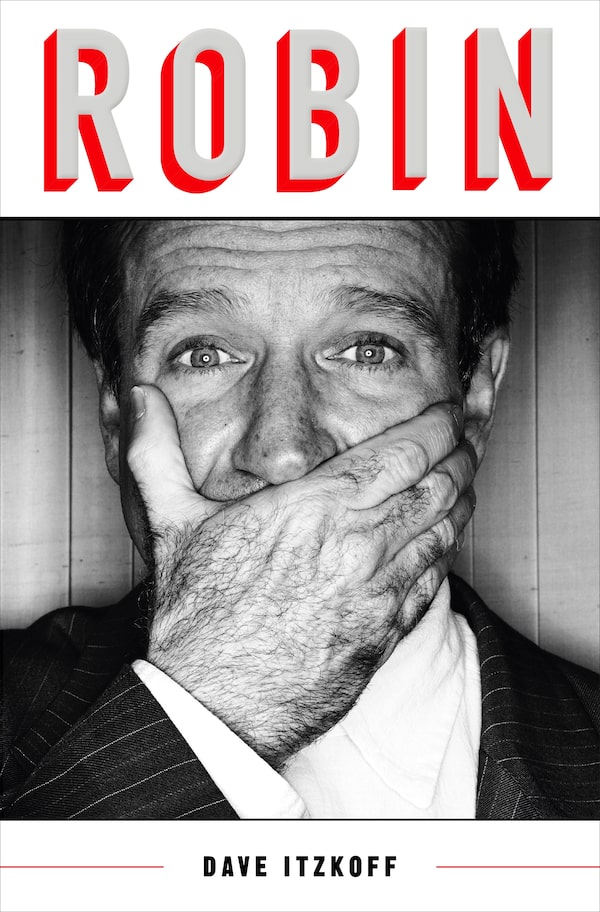

For anyone with a similarly cherished Williams memory, reading Itzkoff’s new biography, simply titled Robin, will produce more than a few throat-lumps. The massive (544 pages) and massively researched book is an intimate chronicle of one artist’s unimaginable highs and severe lows. With dozens of fresh interviews from the likes of Garry Marshall, Pam Dawber, Dana Carvey and practically anyone else who worked or lived alongside Williams during his 63 years – plus exhaustive reporting that looks into every corner of the performer’s life – Itzkoff has created the definitive portrait of the restless and wild human dynamo.

Robin Williams in "Awakenings".

It is also a book that Itzkoff was in a particularly unique position to write. As a seasoned arts journalist, the 42-year-old had interviewed and written about Williams a number of times over the years, including a 2009 Times feature focused on the performer’s return to the world of stand-up comedy after a rough patch involving alcohol, divorce and heart surgery; and a look at his friendship with comedian pal Billy Crystal in 2013. And then, in 2014, Itzkoff wrote Williams’s obituary.

“The only other person I’ve written a book about is Paddy Chayefsky, who I never spent any time with. So there were some instances when writing this when I asked myself, ‘Agh, why didn’t I ask Robin about this when I had the opportunity?’” says Itzkoff, who worked for Details, Maxim, and Spin before joining the Times. “But with a book, I didn’t have to worry about the main constraint I usually do, which is space and word count. Even a passage like in the first chapter, the flourish describing the mansion Robin grew up in and setting the scene, it was nice to have that luxury to be able to slowly and carefully give full descriptions.”

There was a personal connection, too – albeit one that he doesn’t touch upon in his book: Both Williams and Itzkoff’s father, Gerald, were cocaine addicts.

“I don’t want to say it was a one-to-one parallel, but I will say this: The experience I had writing about Robin in 2009, when I was travelling with him on his Weapons of Self-Destruction tour, I felt he had this fascinating candour about himself when it came to talking about experiences while abusing substances, and of going to rehab – it was something I saw and still see in my father,” says Itzkoff, who wrote about his relationship with his fur-merchant dad in the 2011 memoir Cocaine’s Son.

“I don’t know if it’s universal, but there seems to be a common denominator among recovering addicts, this confessional side to them. They want people to know that this is who they were, and that this is who they are now. I saw that in both cases, people who were open about putting themselves out there. They were ashamed of the thing they’d done, but in totality, they were not afraid to be known as, ‘This is who I am. This is on the table.’”

Robin Williams in The Dead Poets Society.

Certainly everything about Williams’s life is on the table in Itzkoff’s book, from his struggles with drugs and infidelity (first wife Valerie Velardi accepted the affairs as “an occupational hazard of stardom”) to the details of his final few hours.

“I was surprised with what people were willing to share,” says Itzkoff on revisiting the events surrounding Aug. 11, 2014, when Williams hanged himself at his Paradise Cay, Calif., home. “Some of that came with time. I would be talking with someone like Billy Crystal, and it was appreciated that he was willing to share his own memories of the last time he saw Robin, and I imagined that he would want to halt the conversation at some point. But he was open. I was asking people to share things that were sensitive, and still unsettled for them. Some people weren’t in a place that they could talk about those experiences, and they may never want to.”

Those include members of Williams’s family. When Itzkoff started the project in 2014, there was a legal battle being waged over the actor’s estate, with Williams’s wife Susan Schneider on one side and his three children (from previous marriages to Velardi and Marsha Garces) on the other. The dispute was eventually settled, and Itzkoff was able to talk extensively with Williams’s oldest son, Zak. Yet, even if he hadn’t received that level of family access, Itzkoff was prepared to forge ahead.

Comedian Robin Williams performing in Toronto on October 17, 1982.Tibor Kolley

“Mercifully, it was a thing I never had to confront. But I reached out to people before in a discreet and careful way when I started the project to say, ‘If this were to proceed, could you conceive of participating in this?’ And while no one was promising to do it, enough people said they’d consider it, to make it a worthwhile project,” Itzkoff says. “When I did get to spend some time with Zak, in the spring of 2016, it was very helpful, and I still had ample time to write.”

Not that writing was such an easy task. Itzkoff worked on the book at the same time he was doing his day job at the Times – profiling everyone from Pharrell Williams to Julia Louis-Dreyfus – and just after the birth of his first son with his wife, singer and actress Amy Justman.

“Having a child was actually helpful because, well he’s obviously a great kid, but it also forces you to use your time wisely – you only get finite amounts of it in any given day, and if you don’t use it, it’s gone. It’s a good bulwark against procrastination,” says Itzkoff with a laugh, who notes he worked on the book during evenings and weekends. “The work ebbed and flowed, too – I spent the first chunk of time focused on the reporting and putting these things together, then to see who was available to speak, and giving people time who might still need to consider the proposition. And there was Robin’s archives at Boston University, where I spent time and I didn’t feel the anxiety of, ‘Oh I should really be doing interviews right now.’”

And whenever he hit a wall, there was always the distraction of Twitter, where Itzkoff maintains a huge audience (about 220,000 followers, more than such high-profile Times columnists as Ross Douthat, David Brooks and Bret Stephens), who come for his of-the-second cultural analysis, liberally sprinkled with memes and Saturday Night Live screen-shots.

Comedian Robin Williams speaks during the HBO panel for "Robin Williams: Weapons of Self-Destruction" at the Television Critics Association summer press tour in Pasadena, Calif. on Thursday, July 30, 2009.Matt Sayles

Asked whether he considers his social-media presence a full-time job in and of itself, Itzkoff demurs, but adds, “My wife might disagree. ... Posting shouldn’t take more than a few seconds, but I understand how those transactions can add up over the course of a day or a week. I’ve been trying to not lean on it quite so much, but honestly, it takes no time at all to just read a headline and come up with a Simpsons quote that references it in some way, and fire it off into the world.”

Those rapid-fire Simpsons riffs are occasionally directed at Donald Trump and his GOP ilk – not an irregular quality on Twitter, but one that might have been expected to dissipate given the Times’ recent update of its social-media guidelines, which now asks its journalists to “not express partisan opinions, promote political views, endorse candidates, make offensive comments or do anything else that undercuts The Times’s journalistic reputation.” One of Itzkoff’s most popular tweets of the moment, however, draws a clear (and hilarious) line between Environmental Protection Agency chief Scott Pruitt and one of Homer Simpson’s more ill-conceived schemes involving used mattresses.

“I don’t want to speak for the company, but I understand why they articulated a more robust policy, as there wasn’t a lot of explaining as to how the people who work here are supposed to conduct themselves on social media,” Itzkoff says. “It’s not intended as a kind of telling people not to engage. It’s telling people to be conscientious on how you do it. I think a lot of people do it very well here, and thrive in all different ways.”

Plus, there are certain parts of a person that just cannot be changed.

“When I wasn’t thinking about Robin Williams,” he says, “I was watching The Simpsons around the clock. It’s in my DNA.”

Barry Hertz is The Globe and Mail’s Film Editor

Barry Hertz

Barry Hertz