Supplied

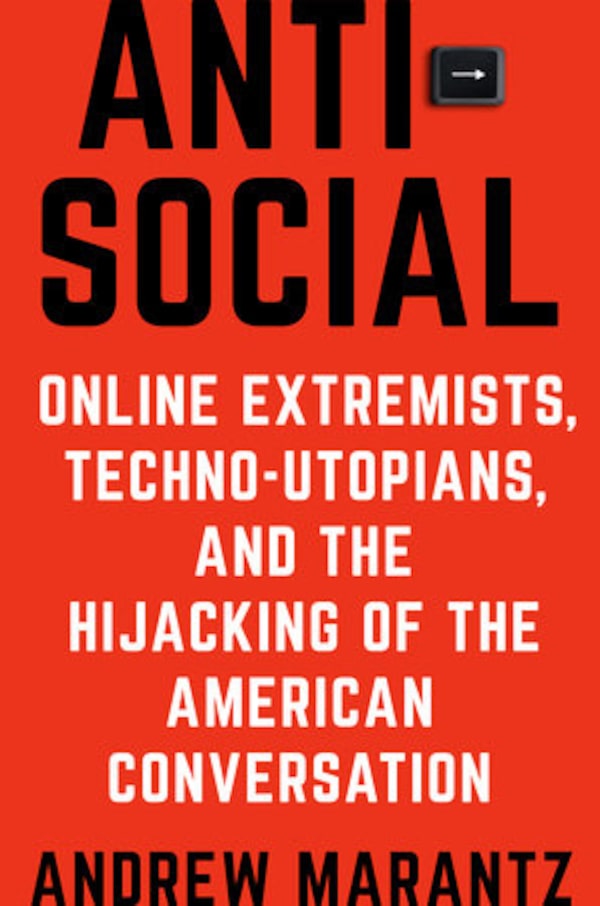

It all seemed so promising. When social-media services such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube launched more than a decade ago, billions bought into their promise of a techno-utopia: people brought together in a worldwide conversation, unleashing their creativity and potential, free to say anything to a global audience, unrestricted by media gatekeepers. But over the past few years, the online world has turned into a nightmare of abuse, incitement to violence and viral disinformation. New Yorker staff writer Andrew Marantz spent three years chronicling what he calls the Big Swinging Brains who created the online platforms, as well as the meme-makers, the Redditors, the disinformation artists and others who have exploited those platforms to sow chaos in the name of cynicism and profit. The Globe spoke with him by phone shortly before the Oct. 7 publication of his Anti-Social: Online Extremists, Techno-Utopians, and the Hijacking of the American Conversation.

You note in your book – and a recent TED Talk – that one of the problems with social-media platforms is their algorithms are built to optimize for what are known as “high-arousal emotions,” which is why content that makes people angry or anxious or fearful is engaged with more often, shared more widely, than nuanced content that, say, makes people think deeply. What should they be built for?

Broadly, I think what you want is some system that values things like truth and civic virtue, and the constructive aspect of community rather than the destructive aspect, and the pursuit of knowledge rather than a corrosive descent into animosity and polarization. I’m not saying it’s easy. I’m just saying it’s necessary if we want our democracies to survive.

No offence, but that doesn’t sound very cool. Of course, you write in the book about your own struggle to accept that, while it’s cool to be a rebel and anti-establishment, there are important reasons for old-fashioned virtues, such as the journalistic standards to which The New Yorker adheres – which sometimes prevent its content from going viral.

There are some things that are just definitionally uncool, and reaffirming and reinscribing the basic norms of your society is always going to be one of those things. So, when I’m hanging around a bunch of goons and crypto-white-nationalists and thugs and weirdos, when I have this feeling that they are being really disruptive and uncivil and racist, and when my impulse is to push back by saying, “Hey, guys, don’t you realize that it’s nice for everyone to get along?” I just automatically sound like Mr. Rogers. It’s very hard for me to be the edgy or cool one in that situation, even though I’m right.

And even though you’re from Brooklyn and, therefore, automatically cool.

Exactly! But the thing is, a lot of these other people are from Brooklyn, too. [Proud Boys founder and Rebel Media contributor] Gavin McInnes invented hipsterdom, and he has way cooler facial hair than I ever will. It just so happens that his ideas are atrocious. I can’t really claim to beat him in the cool race. I just have to kind of try to hope that my ideas can out-compete his in the marketplace of ideas. But one of the main problems that the book tackles is that the marketplace of ideas is broken. And arguably always has been. So you can’t just rely on the better ideas automatically winning.

There’s a central tension at the heart of your project. The trolls such as Gavin McInnes – and some of his colleagues at Canada’s Rebel Media, as well as other highly partisan sites, some of which are bad faith actors peddling unfounded conspiracy theories – literally profit off of attention. But one of the tenets of free speech and journalism is that if you expose noxious ideas to attention and rigorous analysis, they collapse: As the saying goes, sunlight is the best disinfectant. But what do you do when you realize sunlight also helps viruses grow?

Exactly. Yeah, I think “Sunlight is the best disinfectant” is exactly the kind of platitude that if you take it as dogma, it leads you astray.

Yet if we don’t study this stuff, we’re not prepared to fight it. But your overwhelming point is that to give them attention gives them oxygen and capital and life.

Yeah, absolutely.

How do you square that?

I don't think it’s really squareable. I think you have to be rigorous about knowing what you're talking about. But it's also the case that you can write an article that's composed entirely of true facts, that is still missing the larger point. Or it could be the case that you're writing an article, when the better thing to do is not to write an article at all.

That same tension plays out every single day – certainly every single hour that your president tweets.

Or whenever any troll tweets. And there are a lot of people who make their livelihood doing this. [Trump] makes his livelihood through, you know, crime. But they make their livelihood through trolling and there’s just a basic tension where, to rebuke the trolls, to correct them, to respond to them in any way is to let them win. To ignore them is kind of like ceding the point to them, which means they also win. So I don’t see a great way out. Twitter itself could help solve some of these problems. Because [the company is] creating the incentives: financial and attentional and psychological. They are creating the conditions that make people behave this way. It’s not just happening at random.

It calls to mind that famous line from the movie Wargames, where the computer plays a million simulations of nuclear war in preparation to launch a real attack, and then stops suddenly and says: “A strange game. The only winning move is not to play.”

Well, yes. Except that by co-inhabiting their informational ecosystem and just sort of ignoring [the trolls] or watching them silently – you’re still playing their game. You're just allowing them to run the board. I just think we need to build a system that's based on better premises, that is a different kind of game.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Simon Houpt

Simon Houpt