Handout

Another month, another young-adult fiction controversy: Kosoko Jackson pulled his debut YA novel, A Place for Wolves, which was to have published later this month, due to criticism on social media about using the Kosovo War as his backdrop with two American non-Muslims as his main characters.

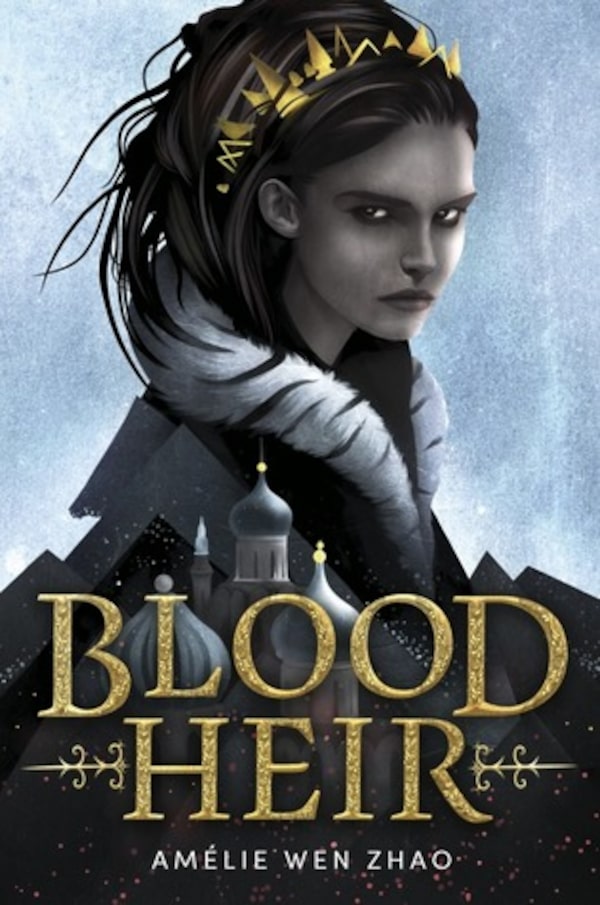

Earlier this year, a fantasy novel by first-time author Amélie Wen Zhao, Blood Heir, was subjected to a wave of social-media criticism before it appeared, mostly by people who had not read the book but who had heard that it contained racist narrative tropes.

This was a complicated accusation, because the book is a fantasy set in a kind of medieval Russia and written by a French-born person of Chinese ethnicity, but it described a fictional slave auction in this fictional world, which offended some American readers who somehow saw it as a reference to U.S. conditions. This triggered a long-running debate among social justice people as to whether Asians can be considered “persons of colour.” The censure was so great that the novelist herself announced that she was withdrawing the book from publication. Zhao has a prominent Twitter presence and like many YA writers has been a vocal supporter of diversity in publishing; she also identifies as a person of colour.

She apologized profusely for her insensitivity. “The issues … in the story represent a specific critique of the epidemic of indentured labour and human trafficking prevalent in many industries across Asia, including in my own home country,” she wrote. “The narrative and history of slavery in the United States is not something I can, would, or intended to write, but I recognize that I am not writing in merely my own cultural context.”

Handout

Mainstream commentators have largely called this a case of internet mobbing, in which the angriest voices were the most powerful but not the most rational.

The repercussions of such an unpublishing are drastic: Zhao had been given a rare six-figure advance for the book, after a publishers’ bidding war. Early reviews were all ecstatic. Such U.S. dramas affect the Canadian industry too, of course, as the Canadian branch of Random House was set to distribute it here and are now sitting on a pile of advance review copies we are not going to see.

This is but one of a series of similar waves of anger over young adult novels that have been accused of some kind of racial insensitivity by Twitter users. Titles such as The Black Witch, American Heart, or The Continent come to mind. (A detailed and revelatory article about controversy over The Black Witch, “The Toxic Drama of YA Twitter,” was published in Vulture by Kat Rosenfield, an industry expert.)

That Kosoko Jackson is now added to this list is particularly poignant. He is gay and black and has been a “sensitivity reader" for YA publishers (i.e. he reads manuscripts to determine if there is anything micro-offensive in them). He was, in fact, himself involved, on Twitter, in the controversy surrounding Emilie Zhao, and not on her side. Now he has written his own abject apology for the “hurt” that he has caused by writing his own book.

Why is this such a common occurrence in this particular sub-genre – dystopian fantasy or sci-fi aimed at teenage readers – and why are the emotions so high in this particular arena? Remember that YA is a very recent category. In the 20th century children read children’s books and then moved to adult books in adolescence. (The Lord of The Rings was not written explicitly for a younger audience.) YA is not a new style of writing or subject matter but a marketing label created by publishing companies. In theory, it is writing for teenagers but in practice we know that it is widely read by adults, and particularly by progressives. It is a left-wing genre.

Because it is so popular and lucrative for publishing companies, it has rocketed to prominence in media coverage of literature. A recent Canadian example – Cherie Di Maline’s The Marrow Thieves – was selected for Canada Reads, a competition usually reserved for adult books.

But despite being taken seriously by adult readers it is still evaluated by educational standards. Literature for children has always been expected to have an edifying component. Talk of freedom of speech and the value of provocation is just called off when it comes to children’s entertainment. We keep a much closer moral eye on entertainment for the young, and we are not averse to blocking it if it seems to impart dangerous lessons. We wouldn’t accept books or movies that encourage our children to take drugs, for example, and it would be hard to make a hero of anyone who tried in the name of art.

YA could perhaps be renamed as moral fiction. Most stories promote the acceptance of the nonconforming, and revolve around this simple device: a marginalized people must fight against an authoritarian power. (The Marrow Thieves is an example of this, as is Blood Heir.)

This genre is far more susceptible, then, to outraged calls for its suppression than adult fiction is, for two reasons (1) all art that claims to be politically progressive is far more liable to be found unprogressive because it asks to be judged by ideological standards (we have seen this in multiple appropriation-of-voice controversies in all art forms in the past few years) (2) literature aimed at the young is always examined for its edifying impact above other considerations.

Much has been said about the ugliness of Twitter-led book-trashing, as if the audience is to blame. But it’s the obsessions of the literature itself that create this environment. YA invites this. We are talking about a genre that is didactic to the point of piety, and generally paints a world of victims and oppressors.

In these simple dichotomies it is often not as progressive as it wants to be. For example, it has been pointed out that governments in such dystopian worlds are almost always oppressive. Governments never provide valuable social services that attempt to balance income inequity, or provide universal health care or protect minority rights. Actual progressive activists are usually quite keen on strong regulatory governments. The pervasive view of government in fantasy YA is curiously aligned with the views of the American extreme right, which sees all government as an intrusion on personal liberty. The repeated message of YA is that all state authority is tyrannical. That, if you want to talk about positive or educational messages, is perhaps not helpful for a fledgling progressive.

But I’m not keen on judging fiction by these standards anyway. Novels that have very confusing messages about public policy – or no message at all – are fine by me too. Perhaps we could introduce teenagers to some of those as well.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.