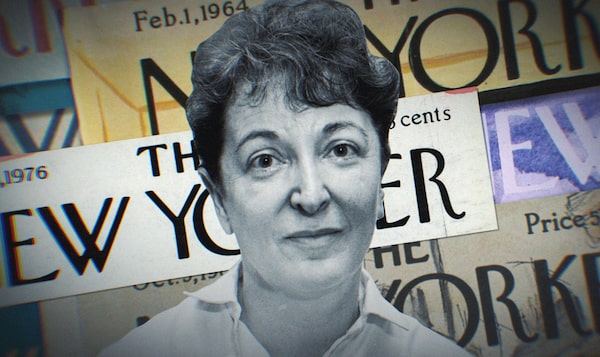

What She Said: The Art of Pauline Kael reviews the life and career of a trailblazing and controversial critic.Films We Like

- What She Said: The Art of Pauline Kael

- Directed by Rob Garver

- Classification PG; 98 minutes

While watching What She Said: The Art of Pauline Kael, I couldn’t help but wonder how The New Yorker’s legendary film critic might have reviewed a new tepid and largely impersonal documentary about her life. (I also couldn’t help but wonder why Sarah Jessica Parker was cast to read segments from Kael’s most incendiary reviews in such cloying voice-over narration.)

This is a woman whose pan of The Sound of Music was so provocative she was swiftly fired from McCall’s magazine early in her career as a critic, and who once decried the nine-hour Holocaust documentary Shoah by claiming the director “could probably find anti-Semitism anywhere.”

Kael’s insensitivity definitely would’ve got her cancelled several times over in 2020, but when she was good, she was very good indeed. For instance, she rescued the critically maligned Bonnie and Clyde with a 7,000-word essay that legitimized the movie’s shocking use of violence as a need for American audiences to confront their relationship with death. Thanks to Kael, Bonnie and Clyde was rereleased in theatres and went on to win two Academy Awards from 10 nominations.

In my perfect universe, Kael’s contribution to film criticism, one that begat a million hot takes and helped solidify the idea that a good critic could come from anywhere, doesn’t get What She Said director Rob Garver’s lukewarm talking-head archival treatment.

What if the late culture writer Nora Ephron had instead penned the story of this boisterous middle-aged woman – born on a chicken farm in Petaluma, Calif., no less! – who would set the film industry ablaze with her pungent, estrogen-laced writing while also being tasked with raising her daughter, Gina, as a single mother on a freelance film critic’s salary?

A movie about Kael is invaluable. She faced systemic misogyny only to accelerate culture with her rapacious desire for movies. No one took her seriously, and then, suddenly, her word became God. After decades of scraping by (she wrote free for decades; an editor at The New Republic continually rewrote her copy without her permission), she reached the pinnacle of her career in her late 40s. Unfortunately, even at The New Yorker, Kael was forced to share her column with writer Penelope Gilliatt as they traded off writing the Current Cinema section of the magazine every six months.

Kael's contribution to film culture deserves more than the talking-head treatment of Rob Garver's new documentary, writes Chandler Levack.Films We Like

In romance, Pauline also never got to meet her equal, preferring to surround herself with a coterie of young intellectuals – as long as they shared her taste. Her daughter took dictation and became her shadow. (I also want a movie about Gina, who fascinates me.)

Kael, who clearly longed for sex and love, found it in the cinema, hence the salacious titles of her writing anthologies I Lost It At The Movies, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang and When the Lights Go Down.

It simply isn’t fair to see director Quentin Tarantino here, blathering about how an errant line in a Kael review inspired Reservoir Dogs. We never hear from the editors she fought to the death, the filmmaker’s careers she silenced with her words and the frenemies she made along the way.

I long for a movie where Kael could also speak for herself about what must’ve been a hard, long and lonely life, offset by the sensuous pleasures of writing about film.

Garver’s documentary, which cuts between archival footage and random movie clips to construct a false cinephilic delirium that is mostly just incoherent, plus interviews with cultural figureheads such as Alec Baldwin (stop), Camille Paglia and Paul Schrader, also merely hints at the misogyny and death threats Kael faced on a daily basis (and this was long before Twitter).

To Hollywood and the critics who despised her, Kael’s personal approach to film criticism could be irrational and dangerous. It also reminds me of how Tina Fey once described the definition of crazy in show business as “a woman who keeps talking after no one wants to [expletive] her anymore.”

Kael continued to make friends and influence people until her death in 2001. Warren Beatty got her a job in Hollywood, producing and co-writing James Toback’s 1981 project Love & Money before she absconded because, ew, who wants to emotionally support James Toback. She made the careers of Brian De Palma and Martin Scorsese, whose early directorial works she championed. She famously set a new standard for what a film review could be – as entertaining as the movie itself, tearing down the institutional walls set by her nemesis, “saphead” Bosley Crowther – a columnist for The New York Times who dared to dislike Bonnie and Clyde, leading to a turf war for the future of cinematic art.

Later, movie nerds formed teams with a polarity as intense as Twilight’s Team Edward and Team Jacob.

If you thought writing about the seventh art should be strictly analytical, you were a devotee of Andrew Sarris (the inventor of auteur theory) and a so-called “Sarrisite.” If you thought film criticism could come with a ton of jokes and sexual innuendo, you were a “Paulette” and a proud champion of trash, as I became immediately, within the first sentence of reading her 1969 essay Trash, Art and the Movies.

Kael once wrote that the power of cinema lies “in the adolescent dream of meeting others who feel as you do about what you’ve seen. … The movie doesn’t have to be great; it can be stupid and empty and you can still have the joy of a good performance, or the joy in just a good line.”

The state of modern criticism has never been so splintered. We create harsher and harsher binaries in our online response to cinema every day, so reading Kael can make you go, “Hey, remember pleasure?” While Garver’s documentary isn’t worthy of its subject’s fascinating artistic legacy, I anxiously await the one that is.

What She Said: The Art of Pauline Kael plays Jan. 17 until Feb. 12 at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema