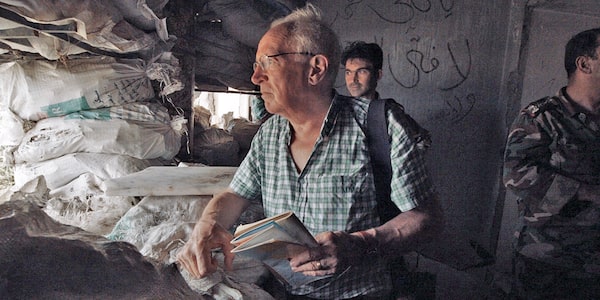

British-born foreign correspondent Robert Fisk is seen here in documentary This Is Not a Movie, by Yung Chang.Courtesy of TIFF

For more than 40 years, the British-born foreign correspondent Robert Fisk has brought the grim, complex reality of the Middle East to Western readers, first for the Times of London and, since 1989, for The Independent. The new National Film Board of Canada documentary This Is Not a Movie, directed by Yung Chang (Up the Yangtze), plays like something of a "Fisk’s Greatest Hits,” following him from the front lines of Syria to the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila in West Beirut, Israel and the Palestinian territories, and Serbia and Bosnia. The Globe and Mail spoke with him this week from his home in Beirut.

TIFF 2019: Updated – The Globe’s latest ratings and reviews of movies screening at the festival

What was it like to have a film crew traipsing after you?

I should tell you, when I was at school, I wanted to be a film critic. I tried to join the start of a local weekly in Kent, in England, so that I could review films, and I used to go up as a schoolboy to watch New Wave films. I’m fascinated by film, because it seems to have an unstoppable power to convince.

What do you think of the result?

I’ve only seen it once, and only very recently, so I haven’t had much time to think about it. This is awful, my first reaction was, “God, what an irritating guy Bob Fisk is, he just waffles on and on and on.” I didn’t yawn at any point, but I felt the need to, occasionally. That’s just me being me.

There’s some nice archival footage of you in Northern Ireland, which you covered in the early 1970s.

When I was sent there as a reporter and I became the Middle East – sorry, Freudian slip, I became the Northern Ireland correspondent, living in Beirut – sorry, in Belfast, there you go again – I was astonished to see that I was reporting a war. I always refer to Northern Ireland as a war and not the Troubles.

Fisk has brought the grim, complex reality of the Middle East to Western readers, first for the Times of London and, since 1989, for The Independent.Courtesy of TIFF

How did covering Northern Ireland influence your subsequent reporting?

At one point, I ran a story and I got a telex from the British Army saying I would no longer be tolerated at British Army headquarters. So I said, “Fine, that’s good.” And an amazing thing happened – and this taught me a lot about the Middle East. I would be walking down a street in Belfast, and a British Army Jeep would pull up next to me, and a young officer would jump out and hand me an envelope and say, “You might be interested in this.” And these were obviously young guys who did not believe the British Army was doing what it was meant to be doing in Northern Ireland, and they would be, of course, official government documents. I realized then that my refusal to go back to the system of press conferences actually stood me in good stead.

At one point in the film, you say dismissively: “I’m not reporting what somebody said on YouTube. If you don’t go to the scene, you cannot get to the truth.” What do you make of the growth of “reporting what someone said on YouTube”?

The problem I think that has come up with technology is that a lot of people who would like to be a journalist think it sufficient to read up on the internet. Sometimes, I get rung up by journalists in the States, who clearly haven’t ever been to the Middle East, and it’s very difficult to explain to them what I think is happening, because what they think is happening bears no relation to the place I live in. They’ve read so much material – from the State Department, from various experts in various places, what I call the Institute of Preposterous Affairs, usually with an address in Washington.

The film doesn’t touch on your current personal life, except to mention that you’re married to a journalist. Was that the director’s choice or did you put that off limits?

It was my decision from the start, as I’ve done with all journalism and all films, is that I will never talk about my private life. Because it’s private.

It strikes me that it might have been good to get a sense of the personal cost of the work that you do, the life that you’ve chosen.

I’m not being nasty to you, by saying no. I’m just saying I never talk about my private life. It’s a rule I kept from when I was in Northern Ireland and before.

Fisk was a correspondent in Northern Ireland during the early 1970s.Courtesy of TIFF

In the film, when you go to the front in the Syrian War, you’re chaperoned by the Syrian Army –

My car, by the way. Not theirs.

Fair enough. Still, do you feel compromised? Especially given that you can’t safely cover the other side of the conflict?

I’ve always said I think this is the worst-reported war in the Middle East, ever, by anybody. Because we can’t get a reporter on the other side. But – compromised? No. My view is every army in the Middle East – and I mean every army – commits war crimes and is brutal. But we’ve got to talk to them, that’s our job. We mustn’t compromise ourselves in doing so, but we must talk to them.

I met Osama bin Laden three times. I didn’t see him after 9/11. I tried to, but I didn’t manage it, but obviously his supporters were attacking Western targets. Should I have gone to talk to him? Yes, of course I should.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Live your best. We have a daily Life & Arts newsletter, providing you with our latest stories on health, travel, food and culture. Sign up today.

Simon Houpt

Simon Houpt