There is a continuing effort to build Toronto’s reputation as a “music city,” but a new book makes a convincing case that Toronto has always been that. The Flyer Vault: 150 Years of Toronto Concert History, published by Dundurn, is a labour of love and dogged research by York University ethnomusicologist Rob Bowman and Toronto music-poster collector Daniel Tate. Divided in chapters by music genres and scenes, the book offers over 170 images of posters, flyers and advertisements, with lively text that sheds light on the city’s relationship with popular music.

The book’s first chapter is given over to minstrel troupes and vaudeville stars, with a history that includes “wild west” shows, concert recitals and the ugly phenomenon of white performers in blackface. The chapters that follow are dedicated to spiritual music, jazz, blues, country, folk, fifties rock and roll, classic rock, musical festivals, soul and R&B, reggae, punk, metal, the Queen Street scene, hip hop and contemporary R&B. “The appetite for live music in Toronto, even before it was incorporated, is phenomenal,” says Bowman, a six-time Grammy nominee for his liner notes. “It’s incredible how quickly Torontotonians were interested in and latched onto and were willing to put their money down for every new form of music as it came along.”

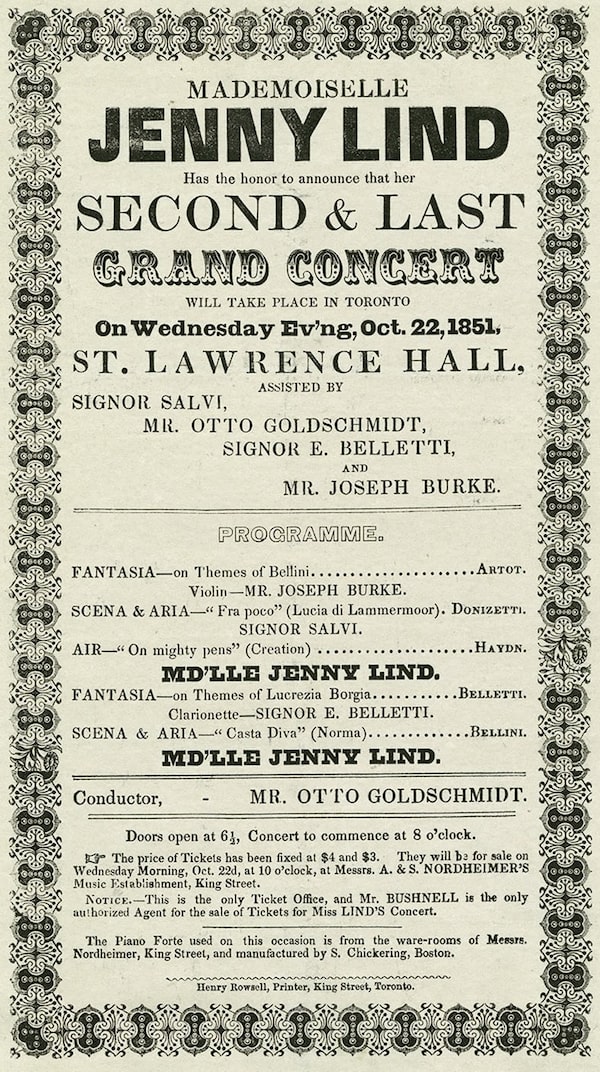

Jenny Lind

How long ago was the Swedish soprano Jenny Lind’s announced second and final appearance in Toronto? She likely arrived to town by stage coach. In October, 1851, the singer gave three concerts at St. Lawrence Hall. Dubbed the “Swedish Nightingale,” her arrival was accompanied by great hype: Her name appeared in the pages of The Globe 91 times in 1850 alone.

“They called it Lindmania,” Bowman says. “She played three nights and for the third night they auctioned off tickets.” This might be the first documented case of surge-pricing in Canada. The face-value tickets for the first two concerts were $3 (which equals approximately $125 today), in an age when seats rarely went for more than a dollar. As the auctioned tickets went for prices that would have represented several months wages for the average worker, the third concert was likely only attended by the very rich. “People went crazy,” Bowman says. Although it was a town of about 30,000 residents at the time, the event was talked about for years after.

Jazz

Handout

Massey Hall gets all the glory, but Shea’s Hippodrome, a few blocks away, was a destination in its own right. Built for vaudeville productions in 1914 by brothers Jerry and Michael Shea, the theatre, with a capacity for 3,200 people, was actually bigger than Massey. “This was one of the places to go in Toronto,” Bowman says of the building set on the southeast corner of Bay Street at Queen Street West, directly across from what is now known as Old City Hall. “It’s tragic it’s not still there.”

Flyers reveal Cab Calloway and his Cotton Club Orchestra made their first Canadian appearance at Shea’s for a six-day stand in 1934 that included five shows on the Saturday alone. On June 27, 1936, Louis Armstrong and his orchestra gave a concert in the “comfortably cooled” venue, with prices ranging from 23 cents to 45 cents a seat.

Bowman believes the first black American jazz musician to play the city was probably Eubie Blake, who, along with Noble Sissle, was responsible for the Broadway show Shuffle Along that settled into the Royal Alexandra Theatre for a week in late September, 1923. “Think about it,” Bowman says. “The first black jazz recording was only made in 1922.”

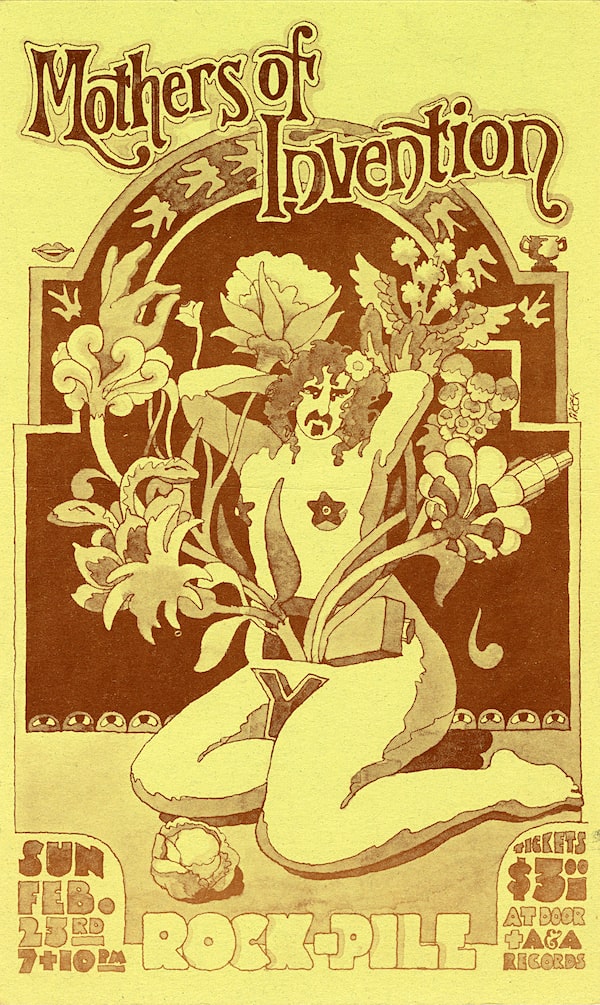

Classic Rock

The Rock Pile rock music venue at the Masonic Temple building at the corner of Yonge Street and Davenport Avenue famously played host to such acts as The Who, Led Zeppelin, the original Fleetwood Mac, Jeff Beck, Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention and, on New Year’s Eve in 1969, Alice Cooper. The posters for The Who and the Mothers of Invention at the Rock Pile were artful and representative of a particularly groovy era.

The Rock Pile was modelled after promoter Bill Graham’s Fillmore venues in New York and San Francisco. The most infamous concert at the venue involved Zeppelin’s second appearance there, on Aug. 18, 1969. The story goes that the band’s manager, the behemoth former wrestler Peter Grant, strong-armed the venue’s managers into a higher fee for his band, saying Zeppelin would leave unless his new price was met. Someone from the Rock Pile went to the parking lot and disabled the band’s equipment van, preventing the band from leaving. Eventually, Zeppelin’s price was met, “nearly bankrupting the place,” according to Bowman.

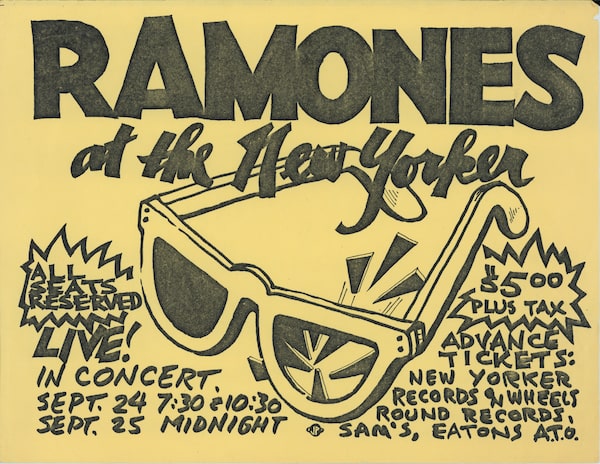

Punk

The book’s chapter on punk, hardcore and grunge deservedly lavishes attention on local promoters The Garys, who were Gary Topp and Gary Cormie, key instigating figures in the development of Toronto’s punk and new-wave scenes. “They transformed the culture of this city,” Bowman says. In particular, a Garys-promoted visit by the Ramones for three concerts at the New Yorker theatre in 1976 was a landmark happening. “Punks started hanging out on Yonge Street and Queen Street," Bowman says. "And people at those shows later formed bands such as the Viletones, the Diodes and many others.”

Bowman recalls an overcapacity Garys show by the Stranglers he attended at the Horseshoe Tavern in 1978. “The Stranglers were spitting at the audience, and the audience was spitting at the Stranglers,” says Bowman, who hung out of bodily-fluid range at the back of the room. “It was mass craziness, but it was celebratory mass craziness. The spitting was a bonding exercise, and I was fascinated by all of it.”

Hip Hop

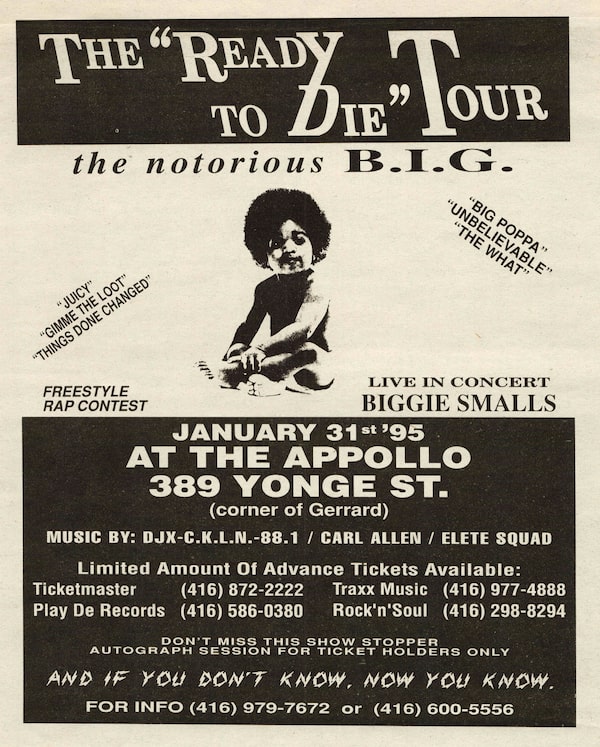

Last year, co-author Daniel Tate posted online a flyer for a 1995 concert by Christopher George Latore Wallace, the American rapper known professionally as the Notorious B.I.G., Biggie Smalls or Biggie. It was held in an obscure basement venue called the Appollo, at 389 Yonge St., at the corner of Gerrard. Not a lot about the show was known, but Tate’s found flyer stirred up social media interest that exploded when a video of the concert was later posted online. The footage went viral, and the notice taken of Tate’s vast, meticulous collection of music promotional items helped lead to the publication of The Flyer Vault book.

“It was the only time Biggie ever played Toronto, and a lot of people had no clue he ever played here,” Bowman says of the rapper who was murdered in 1997, two years after his Ready to Die tour brought him to the city on Jan. 31, 1995. “It was also the only show I’ve heard of at that venue.”

Bowman was going to a lot of shows back then, but he didn’t even hear about the Biggie concert. And yet the now legendary show was packed. How did people know about it? Must have been the flyers.

Live your best. We have a daily Life & Arts newsletter, providing you with our latest stories on health, travel, food and culture. Sign up today.

Brad Wheeler

Brad Wheeler