Douglas Grindstaff, an Emmy Award-winning sound editor who was pivotal in the creation of the indelible whistles, beeps and hums in the original “Star Trek” television series, died July 23 in Peoria, Arizona. He was 87.

His family confirmed his death.

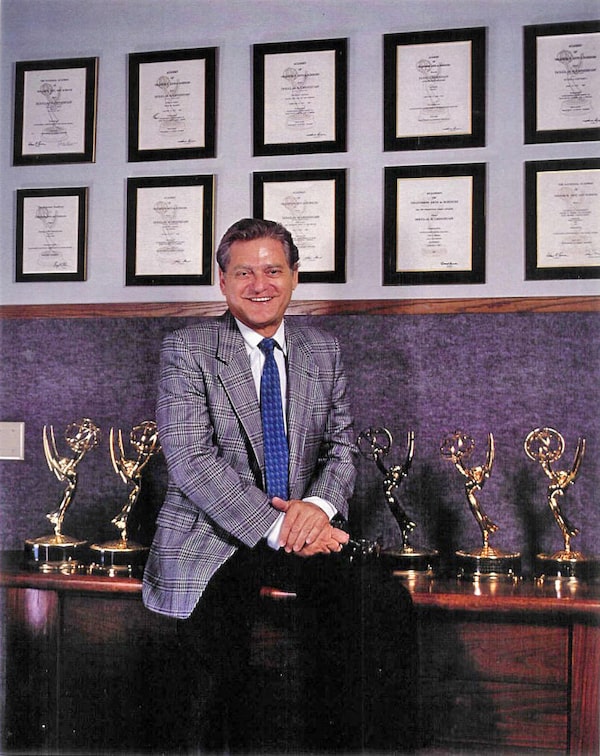

Douglas Grindstaff sits in front of his Emmy awards.PACIFIC SOUND/Pacific Sound via The New York Times

Mr. Grindstaff had numerous sound credits to his name, including the Mission: Impossible television series, Max Headroom and Dallas. But it was his work in helping to bring the Starship Enterprise to life that had the most lasting impact, on decades of science-fiction films and TV shows and generations of Trekkies.

There was the whoosh of the automatic doors opening on the spaceship’s bridge, the gentle coos of furry Tribbles in one of the show’s most famous episodes, and the unsettling wail of sirens when it was time to shift to red alert — not to mention the growl of the cartoonish reptilian alien Gorn (pieced together using, in part, the sound of vomiting) and the high-pitched tinkling of a transporter beam.

The control panel bleeps and bloops provided a familiar ambience for Star Trek while the stars of the show – William Shatner (Capt. James T. Kirk), Leonard Nimoy (Mr. Spock) and DeForest Kelley (Dr. Leonard McCoy) – provided its heart and soul.

Mr. Grindstaff had been working as an audio editor at the Samuel Goldwyn Studio in Hollywood in 1965 when Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, sought his help.

“I had no idea what I was getting into,” Mr. Grindstaff said in 2012. “I had no idea what Star Trek would turn out to be.”

He went to work with other sound editors, including Joseph Sorokin and Jack Finlay.

For Mr. Roddenberry, how the show sounded was essential. Mr. Grindstaff recalled that on arriving for work one morning “the secretary gave me 11 pages of notes that he had dictated to her on one episode.”

Mr. Roddenberry wanted a sense of realism, which meant a distinct sound for each section of the Enterprise. The engineering section, for example, had a murmur different from that of the bridge. There were specific clicks and plinks attached to certain flashing lights. When Sulu, the helmsman, sent the Enterprise into warp speed, the ship flew off with its own unmistakable whoosh. The sound of the ship’s engines was created partly from that of a noisy air-conditioner.

“Each place that you went into on the ship had a different tonality and sound to make it clear to the audience where you were, and that hadn’t been done in science fiction,” Ben Burtt, the sound designer behind many celebrated movies, including the Star Wars and Indiana Jones franchises, said in a telephone interview.

The robot R2-D2’s beeps in Star Wars are the offspring of the console sounds on the Enterprise, he said, and he consulted with Mr. Grindstaff after being hired to work on the 2009 Star Trek reboot directed by J.J. Abrams.

“The key to it – and Grindstaff must have had a good ear for this – the sounds were very musical,” Mr. Burtt said. “When you pressed a button to activate something on Spock’s workstation, it played a little melody. It wasn’t just a single beep or electronic noise.”

In fact, some of the sounds were developed using musical instruments.

“We didn’t have synthesizers in those days,” Mr. Grindstaff said in a 2012 podcast. “I brought in one person, Jack Cookerly, and he had an organ that was rigged up to do electronic sound effects. I had him for one day. That’s all the studio would pay for. He made me a bunch of bleeps.”

Jeff Bond, the author of The Music of Star Trek (1999), said in an phone interview, “Anything that you would think of as an electronic effect on the show was often produced with a Hammond electric organ.”

Mr. Grindstaff said the most difficult sound effect to create was that of the Tribbles, the multiplying nuisances from the Trouble With Tribbles.

“The Tribbles, they would rear up and be mad at you,” he said, “so I’d use a screech owl for that” as well as the sound of a squeaking balloon. In scenes where they were calm, he used the murmuring sound of doves.

For other sounds, innovation required getting his hands dirty, literally. To create one sound effect, he told Cinefantastique magazine in 1996, “I just had a 2.5-ton truck dump a bunch of dirt on a stage.”

“The head of the department just about came unglued,” he said.

Mr. Grindstaff was nominated for an Emmy in 1967 for his work on Star Trek, the first of his 14 career nominations.

But as it happened with the original Star Trek, most of his critical acclaim came later. (Star Trek was cancelled after three seasons because of poor ratings, only to win legions of fans after it began appearing in re-runs and spawning a film franchise.) He went on to win five Emmys.

Douglas Howard Grindstaff was born on April 6, 1931, and grew up in Los Angeles, the youngest of five sons of Forrest and Edna (Hill) Grindstaff. His father was a printer and his mother a switchboard operator.

After serving in combat as an Army sergeant during the Korean War, he found work as a film editor’s apprentice through his brother Charles, who was an associate of Howard Hughes, then an owner of RKO Studios. He worked his way up in the industry until landing a job at the Goldwyn studios – the launching pad for his stint with Star Trek.

After finishing his work with the series, he earned a degree from the California Institute of the Arts in 1975.

He is survived by his wife, Marcia; his children Marla, Charles and Daniel; his stepchildren, Dean Slawson, Eli Slawson and Felicia Grady-Allen; 16 grandchildren; and 13 great-grandchildren.

Mr. Grindstaff became a vice president at Lorimar-Telepictures, the production and distribution company responsible for shows like Dallas and Knots Landing, and headed sound departments at several major studios, including Paramount and Pacific Sound. He was also president of the Motion Picture Sound Editors guild.

If he had a regret, he said, it was that he did not anticipate how wildly popular Star Trek would become after the show had ended.

“If I had only known, I would have kept stuff like you wouldn’t believe,” Mr. Grindstaff said to Audible in 2016. “But I didn’t realize it. No one did.”