Country musician Dolly Parton signs an acoustic guitar for documentary filmmakers Ken Burns, right, and Dayton Duncan in a scene from Country Music.PBS

It was a fella named Harlan Howard who defined country music as “Three chords and the truth” back in the 1950s. For all its catchiness, the pithy label doesn’t explain everything. Far from it. Country music has been among the most daring, imaginative and political cultural currents of the modern United States.

In fact, if you’re looking for America, you will find it in Country Music (Sunday, PBS 8 p.m.), Ken Burns’s epic, eight-part, 16-hour history of the genre. It’s there in all its messiness – the contrarian artists, the hucksters, the racists, the corporate-greed thieves, the broken-hearted and the triumphant people who anchored their artistry in their roots in rural America. The tensions between urban and rural are there, too, and the battling sensibilities of the East and West coasts.

It’s a grand undertaking by Burns and his team, and it is required viewing. It ain’t perfect, though. What Burns does – I’ve seen all 16 hours – amounts to more his-story than her-story, and it’s a bit unduly obsessed with outlaws and rebels, most of them male. Burns has said that, unlike his approach in his previous epic series Jazz and Baseball, he entered the world of country music as an outsider. Like many sophisticates, he probably underestimated and oversimplified the complex social and political meaning of it.

The series (Sunday through Wednesday and the following Sunday through Wednesday) is viscerally rich in music, obviously, and with acres of enchantingly rare archival footage, covers the period from the 1920s to 1996. It ends there because that’s when Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass, died, and Garth Brooks, the last major figure covered, took country in yet another new direction.

It’s a fair decision to map it all out in that timeline. It was in the 1920s that both recording technology and radio took country music out of Appalachia and into the wide world beyond. Before that, of course, waves of Irish and Scottish immigrants to the area had brought Celtic folk music with them, and it eventually fused with elements of black spiritual music to become that unique form of creating, playing and arranging a working people’s kind of music. But that’s anthropology and not the focus of the series.

What is the focus in the superb opening hours is how “hillbilly music,” as it was called for so long, hollered and hymned its way out of a region and, once heard on the new-fangled phonograph, struck a deep chord with people beyond its usual reach. The Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers are at the centre of the story.

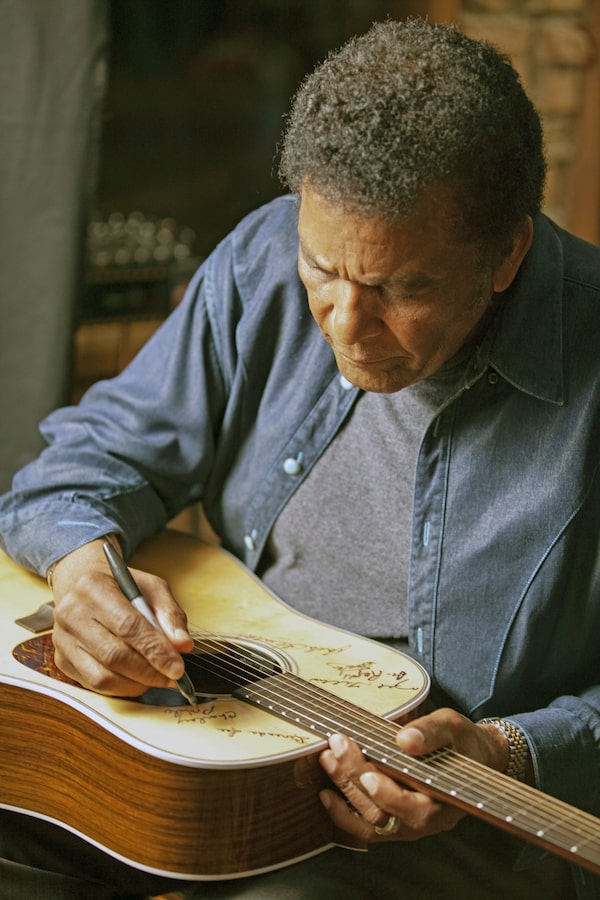

With, of course, a lot of music and acres of archival footage, the eight-part, 16-hour series covers the period from the 1920s to 1996 and features scores of artists, including Charley Pride.Craig Mellish/PBS

It makes sense to start with the Carter Family because as the 16 hours roll out, its influence on a vast array of musicians, in multiple genres, becomes clear. From its church-influenced harmonies to Maybelle Carter’s unique style of guitar strumming, the clan would have an impact for half a century. By an odd coincidence, the day after the Carter Family made its first recording in Bristol, Tenn., in 1927, Jimmie Rodgers came into the studio and recorded. Rodgers had worked as a brakeman on the railway and performed in travelling shows. He was known for his rhythmic yodelling and the style of the songs he recorded in his short life – he died of tuberculosis at the age of 36 – would be copied by countless singers after him.

The second segment in the series, Hard Times, takes us through the evolution of country music in the Great Depression. That’s when radio stations with a huge reach made the hillbilly sound the soundtrack for a despairing people, and the music’s power as a force of protest and lament became obvious. While record sales collapsed, radio was the venue for live performances, and from that came the phenomenon that was the Grand Ole Opry, a weekly radio show from Nashville.

How the Opry made Nashville the centre of country music is part of the spine of the story told. But the series – the main writer and producer is Burns collaborator Dayton Duncan – shrewdly uses an artistic-inspiration distinction to trace the evolution. That distinction is between “Saturday night music” and “Sunday morning music,” with the latter being the music inspired by what was sung in church pews on Sunday, and the former being the music of drinking and celebrating on a Saturday night.

At the core of the series are some central figures: Hank Williams, Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson, although others, including Dwight Yoakam, seen here, appear for some poignant moments.Jared Ames/PBS

In a way, as the series points out, a division that has never quite evaporated. What was once the influence of church became a kind of conservatism in country music, literally conservative and patriotic, and orthodox in its sound. But, always, out there, were outlaws figures whose swaggering version of country would fill vast stadiums, not church halls.

At the core of the series are some central figures: Hank Williams, Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson. Williams is called “The Hillbilly Shakespeare” for his wonderful lyricism and the wit and cleverness of his songs. Still, it doesn’t feel like enough, the time that’s devoted to him. He’s painted as a self-destructive figure rather than the man in constant pain from spina bifida, which he was.

Cash is a figure that connects many dots in the story, his ceaseless curiosity about music and willingness to push back boundaries being a sort of blanket statement about all of country music. And, of course, in marrying June Carter, Cash became inextricably linked to the founding family of the entire genre.

Nelson appears often and maybe too often. One can understand his significance as a pivotal figure. He wrote Crazy, the defining song in Patsy Cline’s short career. And his rebellion against Nashville orthodoxies made him an iconic representative of duelling conventions in the genre.

Key female figures are covered, especially Cline, Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris. But there are times when the treatment feels grudging, as though it were a vexatious pause before moving on to yet another anguished male rebel figure.

At the same time, a male-centric world is what country music is, or certainly has been. And the series reflects that, perhaps just a bit too obviously. And that impulse toward male-centred mythologizing is part of the history of the United States itself. That’s one of the truths that comes with three chords. It’s one of those faults fully on display in what is, in Country Music, an enthralling and vital reflection on America’s heartland and its most significant music.

Loretta Lynn signs a guitar for Dayton Duncan. Burns's most recent examination of a prized American institution features never-before-seen footage and photographs, plus interviews with more than 80 country music artists.PBS

Also airing thus weekend

Preparing for Armageddon (Saturday, CBC NN 10 p.m.) is an odd BBC doc from 2018, profiling people in the United States called “preppers,” who are prepared to survive a global disaster. It’s not just eccentrics, it’s entire communities. Presenter Stacey Dooley starts off skeptical and then she asks, “Should we all be following their lead and making plans for a global catastrophe?”

Live your best. We have a daily Life & Arts newsletter, providing you with our latest stories on health, travel, food and culture. Sign up today.