Paul Taylor and members of his dance company during a rehearsal in New York, Nov. 27, 1972.JACK MANNING/The New York Times News Service

Paul Taylor, who brought a lyrical musicality, capacity for joy and wide poetic imagination to modern dance over six decades as one of its greatest choreographers, died Aug. 29, 2018, in a New York hospital. He was 88.

The cause was renal failure, said Lisa Labrado, a spokeswoman for the Paul Taylor Dance Company.

Mr. Taylor, whose highly diverse style was born in radical experimentalism in the 1950s, created poignant and exuberant works that entered the repertory of numerous dance companies. His own company, eloquent and athletic, has been one of the world’s superlative troupes.

As a strikingly gifted dancer in his 20s, Mr. Taylor created roles for the master choreographers Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham and George Balanchine. He had piercing blue eyes, the power and musculature of a skilled athlete and an incisive, outgoing – but also elusive – personality.

Throughout the fifties, he also made dances of his own – 18 of them with Robert Rauschenberg as his designer, two with music commissioned from John Cage. In 1960, he began to collaborate with painter Alex Katz; although they worked together only from time to time, they continued to do so until 2014, and made two of Mr. Taylor’s most exceptional works, the highly dissimilar Sunset (1983) and Last Look (1985).

With the premieres of Aureole (1962, to music of Handel) and Orbs (1966, to Beethoven), Mr. Taylor broke through to new levels of popularity as other companies started presenting many of his creations. At his own company, Rudolf Nureyev was often a guest star, as well as dancing Aureole around the world.

Mr. Taylor’s company included many illustrious performers, including Pina Bausch and Twyla Tharp, who themselves subsequently became world-class choreographers.

Members of Paul Taylor American Modern Dance perform in "Esplanade" at the David H. Koch Theater in New York, March 8, 2018.ANDREA MOHIN/The New York Times News Service

Mr. Taylor’s Esplanade (1975) was recognized immediately as a masterpiece, and many of the other dances he made between 1975 and 1985 also became classics. Several later works, too, up to at least 2008 (Beloved Renegade, for example), showed the Taylor imagination in full power.

Paul Belville Taylor Jr. was born July 29, 1930, in Wilkinsburg, Pa., and grew up in the Washington area. His father, a physicist, was of French Huguenot descent; his mother, Elizabeth Rust Pendleton, came from a genteel Virginia family. She was a widow with three children when she met and married Paul Taylor Sr., who was rooming in her home.

His parents separated before he turned 4.

“It became clear that my father had become overly attracted to her elder son,” Mr. Taylor wrote in his autobiography, Private Domain, published in 1987.

At Syracuse University, he joined the swimming team on a scholarship. Athleticism became something he was later to champion in dance: Many of his male dancers had powerful musculature, while many of his female dancers displayed lissomeness, force and boldness.

He pursued dance studies in the summer of 1952 at the American Dance Festival at Connecticut College, where Martha Graham became an oracular presence in his life. He followed this by studying at the Juilliard School in New York in the 1952-53 academic year.

In 1953, he became a founding member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company at Black Mountain College; he created a role in Mr. Cunningham’s Septet, a dance still performed today. In 1954, at the Stable Gallery, he met Mr. Cunningham’s long-time designer, Mr. Rauschenberg, who would make costumes or sets for 18 dances created by Mr. Taylor.

On Oct. 20, 1957, Taylor presented the most radical offering of his early career, Seven New Dances. Two of the seven, Resemblance and Duet, set to Cage’s music, had choreography akin to the composer’s 1950s departures from conventional music — using radical stillness and ordinary pedestrian movement. Taylor later recalled audience members walking out. Louis Horst, his former Juilliard teacher, wrote a review of the work in the magazine Dance Observer with a single blank space in lieu of words.

These choreographic experiments nonetheless developed Taylor’s interest in ordinary gesture and nonvirtuoso motion. Henceforth, however, he grew more interested in keeping audiences in their seats.

Mr. Taylor joined the Martha Graham Dance Company in 1955 and remained there for seven years. Clytemnestra (1958) was the most famous dance Ms. Graham created during his time with her troupe; it was also the blockbuster of the long period in which she revisited Greek myth by way of psychology and feminist affirmation. She played the title role; Mr. Taylor was Aegisthus, her evil lover and second husband.

Paul Taylor and Martha Graham perform in Graham's "Clytemnestra" at the 54th Street Theater in New York, May 5, 1960.SAM FALK/The New York Times News Service

Mr. Taylor was already gathering some remarkable dancers around him, including Ms. Bausch (a company member from 1960 to 1962) and Ms. Tharp (1963-65). The tall, long-limbed, dramatic Bettie de Jong joined in 1962, later becoming the company’s main rehearsal director.

In 1961, Mr. Taylor had made dances to Bach (Junction) and Schoenberg (Fibers). But his use of Handel in Aureole displayed a quality of powerfully rhythmic melody and charming blitheness that were departures from the largely tough-grained ethos of modern dance. It caught the Camelot moment of happiness and hope in John F. Kennedy’s United States.

Some of Mr. Taylor’s old artistic colleagues, however, felt that he was courting popularity and compromising his former standards. Mr. Cage, Mr. Cunningham and Mr. Rauschenberg never worked with him again; neither did costume designer Jasper Johns.

Mr. Taylor himself emerged as a skilled writer. Many consider Private Domain their favourite dance book. It is rich in acute intelligence about dance, pungent observations and memorable narrations of the serious and absurd moments of Mr. Taylor’s life.

The memoir reaches its most despairing moment with the injury that curtailed Mr. Taylor’s career, in 1974. This makes a curious end to the Taylor autobiography, for it implies that he – as with many modern-dance creators – was bound up with making dance vehicles for himself. Yet by the time he published Private Domain in 1987, Mr. Taylor had proved the opposite. In the 11 years that followed his withdrawal from the stage (1975-85), he created an exceptional number of enduring classics.

It is often hard to believe that Esplanade, Mr. Taylor’s most widely beloved dance, contains no formal dance step. Its dancers walk, stop, run, skip, sit, jump, fall, embrace and gesture. Everything is very precisely choreographed; patterns predominate. Yet the impetus underlying it is powerful; its moods combine joy and grief, heartbreak and exuberance, memory and impulsiveness; and its spontaneity is often astounding.

With such masterworks, the annual Taylor season became one of the highlights of the New York dance year. Few, if any, companies devoted to the work of one sole choreographer ever matched that of his.

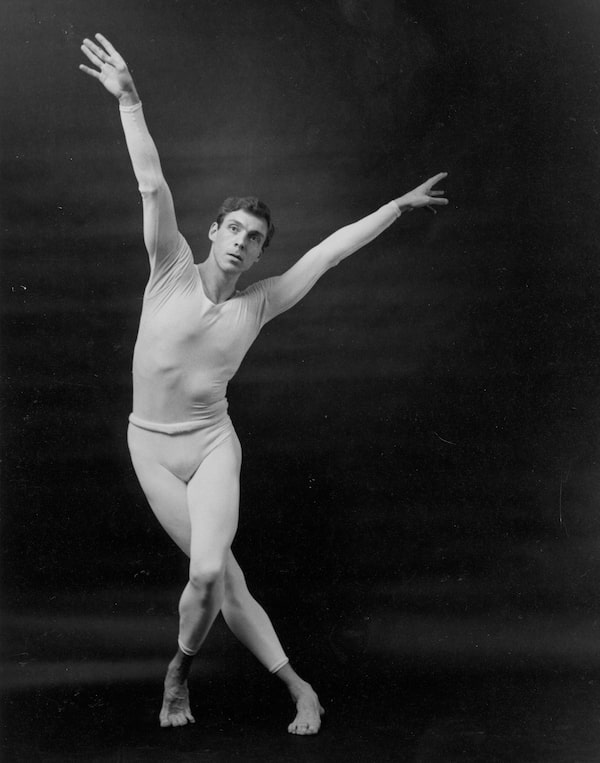

This undated photo courtesy of the Paul Taylor Dance Foundation Archives, shows choreographer and dancer Paul Taylor.HO/AFP/Getty Images

The Taylor company of the eighties was dominated by the lovably heroic Christopher Gillis, who joined in 1976, and by such female paragons as Susan McGuire, Cathy McCann and, especially, Kate Johnson. Guest dancers included Mikhail Baryshnikov, Suzanne Farrell and Peter Martins; other guests were Gwen Verdon, Adolph Green, Betty Comden and Hermione Gingold.

Composer and conductor Donald York became part of the Taylor operation in 1976: He composed new scores, arranged others and conducted entire seasons. The master designer Santo Loquasto first worked with Mr. Taylor in 1987.

After 1986, there were diminutions and depletions. Mr. Gillis died of AIDS in 1993. Mr. Taylor began to use taped music for most seasons between 1991 and 2013. His success rate grew more intermittent, and a few works looked at best half-baked. Later, he sold four works by Mr. Rauschenberg that he had long owned so he could afford to bring live music back.

But many later Taylor dances became beloved, too: Company B (1992), Eventide and Piazzolla Caldera (1997), Promethean Fire (2002) and the aforementioned Beloved Renegade (2008) were among the classics made by Mr. Taylor after he turned 60.

Mr. Taylor leaves no survivors.