Dalbert B Lorino/Globe and Mail

According to Google, I am the only person in the world with the combination of my first and last name—a blessing and a curse in the age of the Internet. And as I build a public profile, I’m grateful for that easy recognition. I’m one in eight billion! But in the past, when it comes to submitting job applications, I’ve sometimes worried my name holds me back. Because my lovely, rhythmical Arabic first name does two things: It identifies me as a woman, and it identifies me as not white.

When I was applying to jobs at two consulting firms a couple of years ago, I submitted applications through their websites and used my initials: H.J. Roderique. I didn't want to take a chance that my resumé would be screened out because of who I am. I made it past the resumé screen and ultimately received offers from both firms.

It’s widely known that job candidates are screened out based on their names, yet few companies have actually changed their hiring processes to address the problem. Sure, there’s lots of talk about bringing in diverse talent, but all too often, it isn’t backed by concrete actions. Changing the way resumés are screened can be a simple way to ensure your company gets access to the best talent and remains competitive. If you haven’t changed screening practices at your company, ask yourself why.

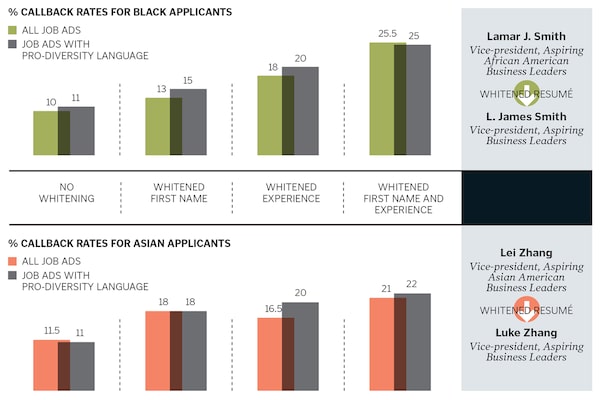

There’s no shortage of research on this subject. Several studies have found evidence of racial discrimination in resumé screening by comparing the callback rates for racialized and white names on fictional resumés. A 2015 study by Michael Gaddis shows that white candidates were 1.5 times more likely to get a response than Black candidates, who also tended to receive responses for jobs with lower salaries and rank. A 2016 study by the University of Toronto’s Sonia Kang and her colleagues found that whitening one’s name got Asian applicants 1.6 times as many callbacks, and Black candidates with whitened names and experience got 2.5 times the number of callbacks when compared with resumés of those who didn’t.

When Jamal becomes James: A study by Rotman School of Management’s Sonia Kang found that resumés with “whitened” names and experience received much higher callback rates

Do I think people are intentionally being sexist or racist when they’re screening resumés? In most cases, no. I ascribe to the statistical model of discrimination, whereby employers use cues—such as gender, parenthood and race—to infer other skills and attributes, like language proficiency, level of education and productivity. That “gut feeling” about someone’s suitability for a particular role or workplace. Because that’s the thing about the “isms” and the phobias around us. They are social, they are structural, and they lead to these inferences, to ascribing meaning, to gut feelings. They lead us to miss the talent that’s out there. Orchestras discovered that the lack of female talent they bemoaned was actually right in front of them once they put up a screen during auditions and evaluated people based on what mattered: the music. Companies can do the same.

It's actually not hard to create anonymized resumés. You can hire a few people at minimum wage to sit in a room for a day and strike out applicants' names with Sharpies. Or with a few simple lines of code, you can tweak your online application system so reviewers don't see the names attached to each resumé. There are artificial intelligence services that offer screening services, but you want to be careful with those—Amazon had to abandon a computer model for resumé screening when it realized the system had taught itself, based on a review of older, mostly male applicants, that male candidates were preferable and penalized resumés that included the word “women's.”

The legal industry, from which I hail, uses a process that is heavily reliant on resumés. In Toronto, candidates submit CVs to get on-campus interviews with large firms. Last year, the firm Lenczner Slaght became the first Bay Street firm that I know of to use an anonymized screening process. Shara Roy, a partner at the firm and cochair of the firm's Student Committee, told me that reviewers found looking at the anonymized resumés “quite jarring” and that it made people more aware of why they were connecting to certain applicants.

If your company is nervous about diving right into this kind of process, try an experiment. Dig up all the resumés that were submitted for a position that has since been filled, put together a new review panel and have them review resumés without gender, racial or other cues. Then compare those candidates to the one who was actually was selected. If you find a discrepancy, you need to address it, be it via anonymized screening or another method.

Of course, changing how you screen candidates is just a baby step in addressing hiring inequity. Hiring managers need to look at who gets judged on potential versus what they’ve accomplished, over-reliance on certain credentials, how requirements are applied or waived, and generalizations about candidates. And that’s just hiring; more problems abound in performance evaluations, assignment of work, compensation and meetings, to name a few. But changing the screening process is a good first step in a series of transformations a company needs to take if it really is interested in drawing top talent. Roy concurs: “It has to be part of a broader commitment and a broader change.”

From a numbers perspective, the ratios we see at the top of our elite organizations can’t be reflective of the reality of our talent. If they were, and bias weren’t a factor, we would see this reflected further down—university classes and dean’s lists composed of mostly white men. But we don’t. In Canada, 56% of university graduates and 51% of people with a master’s are women. Looking at my own field, law, we see that women have comprised half of the law graduates for the past 20 years in the U.S., yet are only 22% of partners at major law firms.

In this increasingly knowledge-based world, Canadian companies need to attract the best people possible if they want to stake their claim here at home and around the world. Relying on only a portion of the available talent pool isn’t going to cut it. And as the battle for the best brains gets tougher and tougher, Canadian companies’ future survival—and our society’s ability to thrive—depends on it.