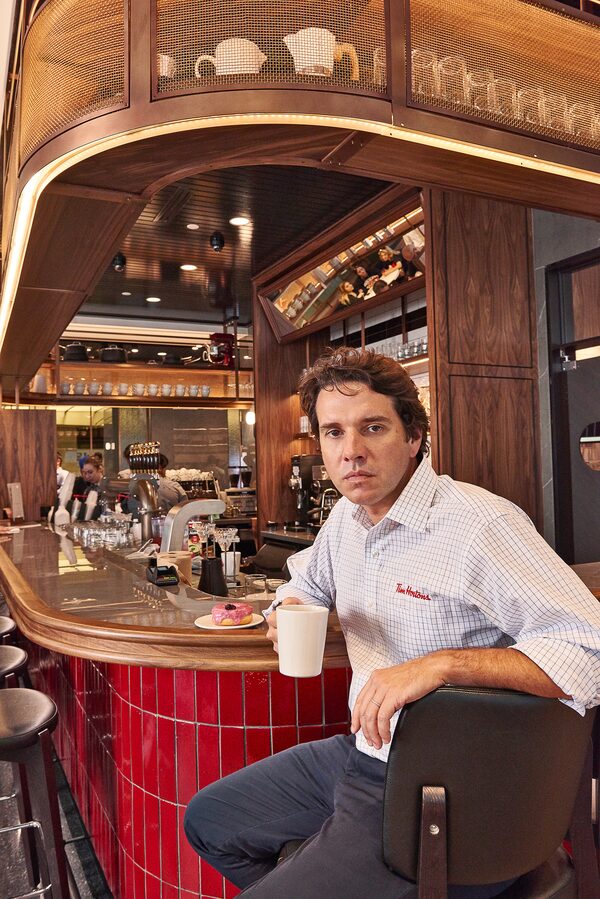

Alexandre Macedo sits in the new Tim Hortons Innovation Café in downtown Toronto.Dermot Cleary/The Globe and Mail

Few people who roll up the rim have any idea that, for the past five years, Canada’s favourite coffee and doughnut brand has been the property of a Brazilian private equity firm called 3G. When 3G bought Tim Hortons in 2014, it paired it with its other fast-food acquisition, Burger King, and made them two arms of a company called Restaurant Brands International. (RBI has since added fried chicken brand Popeyes to the fold.) It’s clear by now that the 3G-RBI team runs the same playbook with each acquisition: Clear out the old guard, clamp down on costs and install energetic young executives willing to do what’s necessary to hit their numbers. And now you know why a Brazilian-born 42-year-old, Alexandre Macedo, prowls around the vast open-concept head office of Tim Hortons like he runs the place. Not quite two years ago, fresh from helping turn around Burger King North America, the marketing hot shot with an Insead MBA was parachuted in to fix what RBI’s first three years of Tim’s ownership had wrought—a franchise system in turmoil and a once-sterling brand reputation heavily tarnished. Today, Macedo still has work to do. But he has used his decisive charm to calm the franchisee waters, and the expansion is picking up speed. Now the president has another task—this interview—to tick off his list, and he attacks it with the same smiling confidence.

You were the head of Burger King. Why did you take this job?

I don’t see myself as a Burger King or a Tim’s person. I work for RBI. I think some of the challenges we were having here at Tim’s were not too different from some of the challenges we had at Burger King when we bought the brand. And I felt that I could help solve this—despite not being too familiar with the brand at the time. I have a very big marketing and operations background, and I learned how to work well with franchisees. It wasn’t easy. I became the president of Burger King when I was 35. It wasn’t easy for them to accept me. I had no experience. It was tough, and I learned how to do that. So the challenge here wouldn’t be too different.

Does RBI get its corporate culture from 3G?

No. People have this thing about 3G. 3G is a group of, I don't know, six or seven people. I don't think I've ever been to the 3G office in New York. We have our own culture. It's an RBI culture.

How would you define it?

We are people who have very big aspirations for our brands, and we don't shy away from working really, really hard to achieve those big aspirations.

Since 2014, when RBI bought Tim’s, it’s been a rocky ride. Would you agree?

It's been a rocky ride. Yes.

What’s been the hardest part?

It’s been loud in the press. But believe it or not, the business has grown significantly since we acquired it. System sales are much bigger than they used to be. We’ve built 450 restaurants or more in Canada alone. We got into seven new countries. (1) Franchise profitability in Canada is much higher than it was in 2014. Our restaurants in Canada are some of the most profitable restaurants in the world.

So, it really should be a good-news story for Tim Hortons, and yet it hasn’t been.

We had a tough time, the first team that was here, in working together with our franchisees. Some of my colleagues weren’t experienced with Tim’s, and that led to a lot of unrest with the franchisees. The relationship is at its best when you have good results and a good plan that franchisees understand they are a part of. I’ve focused 95% of my time in the past year trying to make sure we were on that page.

Last year you said, “We have decided to communicate better.” Why was that decision necessary?

At Burger King, I learned you have to create a common language. If you don’t explain to the franchisees how you look at the business, what things are going well and what things aren’t, it’s very difficult to communicate. It’s very dark. When people feel they don’t have information, they get very anxious. If you build a common language, people understand what’s going on.

That wasn’t happening before you arrived?

We didn’t have a cadence. We didn’t listen to the franchisees in a structured way. So, I’ll give you a few examples of what we did. Last week, the team came back from travelling all over the country. I’ve travelled all over the country three or four times. These are structured visits in hotels, with content, with microphones, with a program. We ask franchisees about their confidence in the team and in the plan before these meetings, and then we ask them again at the end of the meeting. We have a biweekly webcast. We share our results, what’s working and what’s not, what’s coming, what has to be adjusted. We meet with our advisory board every quarter, and we have calls with our subcommittees every month. If you think about it, we have about 1,500 families that manage our restaurants in Canada. On average, these families have been managing restaurants for over 10 years. That’s 15,000 years of experience. Not tapping into that is foolish and arrogant.

Former Canadian Tire executive Duncan Fulton was brought in last year to help repair relations with the franchisees. What was he able to do that you weren’t?

I think Duncan has 20-plus years of experience in the landscape in Canada. He allowed me to understand a little bit more about how decisions are made and how to communicate with the franchisees on some of the tougher issues. Not so much on the business side. His experience isn’t in franchising, and it isn’t in what we do in restaurants. But in managing some of the tougher issues we had with the franchisees, he was absolutely critical for us to learn.

You recently settled two franchisee class-action lawsuits. (2)

They weren’t settled, because we didn’t admit to guilt. I mean, they were settled, but it wasn’t like an admission of guilt. I see it as something we had to put behind us.

Is there something about the RBI approach that leads to conflict with its franchisees?

If you look at RBI, when we took over at Burger King, we never had an issue. We bought Popeyes. Nothing. Internationally, it doesn’t happen. We had an issue here in Canada. I would attribute it to perhaps a lack of knowledge here. This brand is such an amazing, beautiful, relevant, big brand that it’s different from some of the other brands we are used to working with. And maybe the leadership style of some of the team members here didn’t resonate very well. But I don’t think it’s an RBI thing.

That leadership was brought in by RBI.

Yes, yes, yes, yes.

The Innovation Café will allow Tims to test products aimed at a younger, more urban customer base.Dermot Cleary/The Globe and Mail

When RBI bought Tim Hortons, a lot of managers and executives were let go. Was anything lost in that process?

We tried to keep some of the most relevant contributors. The president for Canada was David Clanachan. He remained. The president for the U.S., David Blackmore, remained. We kept all of our field team. Most of the people who exited had common back-of-the-house functions with Burger King. So there was a lot of noise, but we preserved most of the business-function people.

Yet you had trouble with the brand.

I think we had trouble with the franchisees more than the brand. Because as I mentioned to you, the business results, particularly in the first two years, were very, very good.

Léger Marketing reported that Tim Hortons’ brand reputation dropped from fourth to 50th last year. What explains that?

A small group of franchisees decided to bring to the public issues that, in general, are kept not in the public eye. The nature of franchising is friction. Just enough friction between franchisor and franchisee is really good. But it’s not good for the brand to bring those disagreements to everyone. (3) That created another big wave of negative press. It was my first week here, in fact. That was a tough one for us.

You landed—

I landed in the trough, yes.

What did you do?

I met with those franchisees who were a little bit unhappy. We put together a plan that the vast majority of the franchisees were behind. And the plan yielded good results. Is it exactly where I want to be? No. But we started to show that the brand was strong and alive again.

Sales growth for Tim Hortons is weak compared to Burger King and Popeyes over the first half of this year. Why?

So our focus is, we are going to be here for a long time. Tim Hortons is by far our strongest brand. We think the potential to make it even better in Canada is big. We can do wonders in the U.S. I am a believer. And we are just starting to tap the potential for all over the world. There are no short-term tricks for a brand this big.

But what’s behind the struggle this year with sales growth?

Well, it’s not a struggle. I think we have to upgrade a lot of the areas of our business so we can start growing a lot. We are doing things that should have been done a long time ago. I will give you an example: our coffee lids. We have had issues with our coffee lids for 20 years. They spill; they pop off. We changed the coffee lids. We are now changing our brewing equipment in every single restaurant in Canada. (4) It’s probably the biggest initiative on product quality the brand has ever undertaken.

I’ll ask one more time if you will acknowledge that sales growth this year has been weak so far?

I would've hoped to do a better job in driving sales. Yeah.

You mentioned the U.S. You haven’t been happy with how the expansion into the U.S. is going. (5)

I have not been happy. I think the U.S. is challenged. Over the years, I think Tim Hortons treated the U.S. as an extension of Canada. Our brand is so unique in Canada, so powerful and so present in everyday life that I think the U.S. should be treated as a different market. As an international market. We need to adjust the business model so we can grow in the U.S. Because in the U.S., we don’t have the penetration, and we don’t have the brand awareness.

You’ve opened 16 stores in China, on your way to 1,500. What have you learned so far?

That our beverages are extremely well accepted in China. And that the combination of being a café with freshly prepared food is unique to us.

Why is it unique?

Perhaps our main coffee competitor in the world—we don’t use names—they don’t have freshly prepared food. So having the freshly prepared food for breakfast and lunch actually is a big deal in China. The biggest success in China—I think we are winning on design. The restaurants are beautiful. We did something even more contemporary and more modern than we did in our renovation here in Canada. And that’s going to be our image for most of the markets outside Canada.

RBI is a very data-driven company. What does the data say about the typical Tim Hortons customer?

We serve eight out of 10 cups of coffee in Canada. We are so big that we are across the board. That said, we have an opportunity to increase our penetration in a more urban and younger consumer profile. We can do a better job of serving more of the millennial guests and more in urban situations. That’s why we have the Innovation Café. (6) It allows us to stretch the limit of the brand a lot and to be very playful without putting the franchise business at risk. We have to continue to innovate beyond our doughnut platform. You can’t change very drastically in Canada, because people have a deep emotional affection for the brand. So you have to be careful. We don’t have to blow anything up. We just have to remain contemporary.

Whose idea was the hockey focus of the Innovation Café design?

Our design team said, “Alex, considering we are Tim Hortons, I think we lack references to hockey in our restaurants.” I said, “Yeah, but just make sure we're not cheesy about it.” My favourite is opening the door with a hockey stick. That, for me, is genius. We are actually going to put the hockey stick in every restaurant in Canada.

Footnotes

- Tim Hortons can be found in the Philippines, the U.K., Mexico, Spain, China and five coutnries in the Middle East. It plans to open stores in Thailand early in 2000.

- The lawsuits, led by the Great White North Franchisee Association, alleged that RBI misused money from a national advertising fund and interfered with franchisees’ right to assicate. The settlement was valued by a judge at $37.4-million, including non-monetary amounts, although Tim Hortons insists it paid only $12-million in cash.

- In late 2017, in the wake of Ontario’s minimum-wage hike, two franchisees disregarded head-office directives and made cutbacks to employee benefits and scheduled breaks to offset increased salary costs, prompting a widespread boycott.

- The iconic glass carafes are being phased out in favour of stainless steel “FreshBrewers” to ensure consistency.

- There are approximately 700 Tim’s stores in the United States. The most successful are in Detroit and Buffalo. A representative for franchisees in Minnesota said in May that “all locations are bleeding money.”

- This corporate-owned café in Toronto’s financial district will allow Tim’s to test products aimed at younger, more urban customers. The company plans to put more of these cafés at downtown locations in other Canadian cities next year.

Trevor Cole is the award-winning author of five books, including The Whisky King, a non-fiction account of Canada’s most infamous mobster bootlegger.