The sun is already setting as we head out on a quad toward the mouth of Sundance Creek, rumbling down a rocky path. Billy Beardy leads the way, a hunting rifle resting next to his rubber boot in case of trouble with wolves, black bears or, on the off chance, a polar bear.

When we reach a steep pitch, he stops and calls out to his wife, Tamara, who is driving the quad behind.

“Make sure you hold your brake,” he tells her before pushing the throttle back up.

We travel nearly four kilometres, branches smacking our faces as the trail narrows to the Nelson River. Along the way are boundless stands of tamarack, black spruce, jack pine and poplar, packed tightly together into an nearly impenetrable fortress of trees.

This is where B.C. murder suspects Kam McLeod and Bryer Schmegelsky hid.

“So now you know how hard it is to see somebody from here,” Mr. Beardy says on a cool September evening, his light green eyes fixed on the wilderness ahead.

A month has passed since the Cree trapper was with the Manitoba RCMP on the hunt for Canada’s most-wanted fugitives. He was there that Wednesday morning when their lifeless bodies were found lying in thick brush near the Nelson River. His sharp eye and intimate knowledge of the land helped the Mounties end one of the most intense manhunts in Canadian history and bring relief to terrified residents of Fox Lake Cree Nation and Gillam.

The extraordinary discovery came in the nick of time.

That very day, after more than two weeks of searching, the Manitoba RCMP were preparing to wind down the manhunt. They believed Mr. McLeod and Mr. Schmegelsky were dead, but unsure if they would ever find them.

Until a raven appeared.

0

200

0

12

KM

KM

MAN.

MANITOBA

Detail

280

290

ONT.

Gillam

Winnipeg

U.S.

0

200

Provincial Rd 290

m

Suspects’ burned-

out vehicle found

Sundance

Creek

ATV trail

Nelson

River

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: GOOGLE EARTH

0

200

0

12

KM

KM

MAN.

MANITOBA

Detail

280

290

ONT.

Gillam

Winnipeg

U.S.

0

200

m

Provincial Rd 290

Suspects’ burned-

out vehicle found

Sundance

Creek

ATV trail

Nelson River

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: GOOGLE EARTH

0

200

0

12

KM

KM

MANITOBA

MAN.

Detail

280

290

Stephens

Lake

ONT.

Gillam

Winnipeg

U.S.

0

200

Suspects’ burned-

out vehicle found

m

Provincial Rd 290

Sundance

Creek

ATV trail

Nelson River

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: GOOGLE EARTH

The Beardys’ home hums with the frenetic energy of four children, three cats and four dogs, who bark at the arrival of visitors.

The family lives in a grey siding-clad house in Bird, a Fox Lake Cree Nation community of about 200 people in the middle of the rugged northern boreal forest.

From Bird, it’s a long drive to anything except the woods. The reserve is some 55 km from the nearest grocery store and gas station in Gillam, a small blue-collar town of hydro workers. The isolated communities are connected by two main gravel roads, and both dead end at the bush. This isn’t an easy place to get to or an easy place to leave.

The first homes in Bird went up in the early 1970s and were little more than shacks. There was no running water or electricity. Residents chopped wood for heat and light and shared food from their fishing and hunt trips.

Despite the hardships, the new community was their haven from a rapidly expanding hydroelectric industry that had muscled into Fox Lake’s traditional territory in the sixties, bringing with it a more acute racism that made life in Gillam untenable for some Indigenous people.

Mr. Beardy was a year old when his family moved to Bird in 1971. While many Fox Lake band members now reside in bigger communities such as Thompson and Winnipeg, he has never wanted to live anywhere else. He is most at home out on the land, and that’s where he was when the B.C. murder suspects arrived on Bird’s doorstep.

Some of the Beardy children and their cousins play in the back of the Beardy family home in Bird, on Fox Lake Cree Nation, in mid-September.

The Beardys were on their way home from picking strawberries with their youngest daughter, Pesim, when the couple spotted black smoke billowing into the evening sky on July 22. They weren’t sure what was on fire and drove over to check whether anyone was in danger.

The couple found a vehicle engulfed in flames in a ditch next to Provincial Road 290, near Sundance Creek. Worried that someone was trapped inside, Mr. Beardy told his wife and daughter to stay in the truck as he checked, but the flames and smoke were too intense and he backed away. Mr. Beardy called the RCMP, and the family waited for about 45 minutes for emergency workers to arrive.

Drawn to the scene by the smoke, a group of nearby residents and power workers gathered to see what was going on. There were tire tracks and matches on the ground. To Mr. Beardy, it looked as if the vehicle had been pushed into the ditch and set alight. The couple wondered whether it had been torched as part of an insurance scheme.

Detail

0

12

KM

MANITOBA

280

290

Gillam

Suspects’ burned-

out vehicle found

290

Nelson

River

Limestone

River

Bird

Limestone Generating Station

0

1

KM

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: GOOGLE EARTH

Detail

MANITOBA

280

290

Gillam

0

12

KM

Suspects’ burned-

out vehicle found

290

Nelson

River

Limestone

River

Bird

Limestone Generating Station

0

1

KM

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: GOOGLE EARTH

Detail

MANITOBA

Suspects’ burned-

out vehicle found

280

290

Gillam

0

12

290

KM

Nelson

River

Limestone

River

Bird

Limestone Generating Station

0

1

KM

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: GOOGLE EARTH

The suspects' SUV, as photographed by Billy Beardy while it was still on fire, and the site as seen from the air a few weeks later.

It wasn’t until the next day that they realized the vehicle matched the grey 2011 Toyota RAV4 that police were seeking in connection with the disappearance of Mr. McLeod and Mr. Schmegelsky. Initially declared missing by the RCMP in British Columbia, the pair were now considered suspects in the deaths of three people killed over four days in Northern B.C.

On the run, they had last been spotted in Northern Saskatchewan, the RCMP said. In truth, they were already well past the province’s boundary by then. On July 24, the RCMP confirmed to the public what the Beardys already knew: the SUV found on fire near Bird had been driven by the murder suspects. Where they were now, no one knew. Mr. Beardy wonders how close he and his family were to encountering the alleged killers. “They could have been watching us,” he says, sitting next to his wife, Tamara.

“That’s what bothered me,” his wife adds, “knowing that anything could have happened to us while we were sitting there.”

Listen to Billy and Tamara Beardy recount their first 48 hours of the manhunt.

The challenge of finding the fugitives initially fell to Inspector Kevin Lewis, who at the time oversaw the operations of 22 detachments in the Manitoba North District. The affable commander comes from a family of police officers in Thunder Bay and had been with the RCMP for 17 years, policing in all three territories before joining the Thompson detachment in 2014.

He was used to pressure, but the manhunt for Mr. McLeod and Mr. Schmegelsky was like nothing he’d experienced before.

“There’s so much desolate land out there in Northern Manitoba that it’s so hard to search every inch of it,” he says, reflecting on the operation. “It’s a needle in a haystack.”

Manitoba RCMP Inspector Kevin Lewis was initially in charge of the manhunt.

With the discovery of the car, dozens of RCMP officers swooped into the region with assault rifles, sniffer dogs, drones and quads. A police plane equipped with an infrared camera flew over the area, but detected no heat signature of the suspects.

The dogs didn’t pick up a scent because too much time had passed between when the vehicle was found and when the manhunt began in earnest, two days later.

But even as they scoured the area, the Manitoba Mounties were theorizing that Mr. McLeod and Mr. Schmegelsky were long gone.

They could have followed the rail tracks and hopped on a train or hitched a ride with a passerby in an area where few think twice about helping a stranger on the road. They could have found a boat by the Nelson or trekked along one of the hydro corridors. They could be hiding in a trapper’s cabin or even made it as far north as Hudson Bay by now. With so many possibilities to consider, the RCMP’s search took in 11,000 square kilometres.

Mr. Beardy was feeling the pressure, too. While the police broadened out their focus, the local community was on high alert. Many residents in Bird were too afraid to leave their houses and struggled to sleep.

Despite their nearby sweeps with drones and planes, no RCMP officers were stationed in Bird. Instead, they based their operations in the larger community of Gillam. Realizing their community needed protection, Mr. Beardy and other Fox Lake band members began patrolling the many gravel roads and quad trails around Bird and kept watch over the community day and night.

A proficient trapper and construction supervisor, Mr. Beardy, 48, was seen as a leader in his community – the man many turned to when something needed to be fixed or found. He wasn’t a big talker, except if he was telling hunting and fishing stories. Few, if any, knew these northern lands and waterways better than he did.

“Anytime we’ve had any crisis, he’s come forward and demonstrated this leadership,” Fox Lake Chief Walter Spence says. “He’s quiet, strong. He does what he needs to do, without any hesitation, without any complaints.”

Mr. Beardy’s gut told him the men had not gone far. He kept driving around the abandoned Sundance work camp, checking to see if any trailers had been broken into. From his truck, he scanned the gravel trails, looking for anything that appeared different from the day before. A boot track. The ashes of a camp fire. Animal bones.

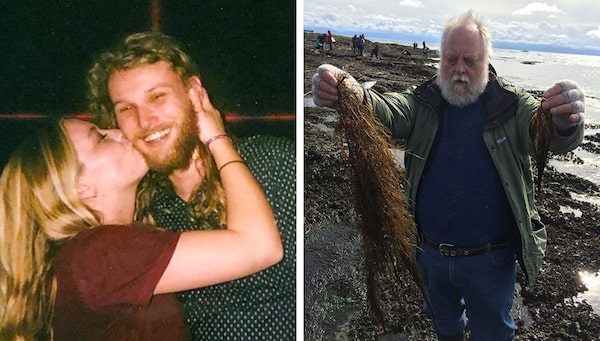

The fugitives were being pursued for the killings of Chynna Deese, Lucas Fowler and Leonard Dyck in Northern B.C., shown in a series of handout photos from social media and the University of British Columbia, where Mr. Dyck worked.

The eyes of the world were fixed on Northern Manitoba as the manhunt dragged on. The killings of tourists Lucas Fowler and Chynna Deese, and Vancouver resident Leonard Dyck had captured the attention of both Canadian and international media.

Mr. Fowler and Ms. Deese were a young couple in love. He was a spirited adventurer from Australia, the son of a chief inspector for the New South Wales Police Force. She was a generous soul who volunteered at a camp for special-needs families in her hometown of Charlotte, N.C.

They were shot to death on July 15 near the popular Liard Hot Springs in Northern B.C., multiple bullets tearing into their bodies. Four days later, the white-bearded Mr. Dyck was found dead near Dease Lake, about a 500-km drive southwest of the hot springs. The 64-year-old was a sessional lecturer at the University of British Columbia’s botany department out on one of his characteristic outdoor research trips. He, too, had been shot, but also battered and burned.

The B.C. RCMP did not release photos of Mr. McLeod, 19, and Mr. Schmegelsky, 18, until July 21 and took two more days to declare them prime suspects in the three killings. At a news conference in B.C. on Sept. 27, the Mounties said they first spoke with Mr. McLeod’s family on July 19 and Mr. Schmegelsky’s family the next day, and were told the young men were “good kids.” Based on those interviews and their lack of criminal records, the police didn’t suspect that they were the killers. In fact, they thought they could be further victims.

Kam McLeod and Bryer Schmegelsky, as seen in a a public alert issued by the B.C. RCMP on July 23.

But in their hometown of Port Alberni, B.C., a disconcerting picture soon emerged of Mr. McLeod and Mr. Schmegelsky.

They had an interest in Nazism, Soviet Russia and survivalist video games. Mr. Schmegelsky had a history of making disturbing and violent comments about killing people and then himself. Many who knew them had considered their behaviour odd and unsettling, but not dangerous.

When the teens left July 12 in a vintage Dodge Ram pickup truck with a Bigfoot camper top, they seemed to be headed to Yukon and Northwest Territories in search of work. At least, that’s what they told their parents.

Why they came to a road to nowhere in Northern Manitoba, in some of the harshest terrain in the country, remains a mystery.

“It doesn’t make sense to me,” Insp. Lewis says.

During the first week of the wide-ranging manhunt, there were about 40 police officers involved in the search and working flat-out, searching as far as Churchill. Two military aircraft joined the effort on July 27: a Canadian Air Force CC-130H Hercules, staffed with trained search-and-rescue spotters, and a CP-140 Aurora that had specialty surveillance capabilities, including infrared camera and imaging-radar systems. But they didn’t spot anything significant.

The Mounties were flooded with more than 1,500 tips from the public, but with no concrete leads or new sightings of the fugitives, Insp. Lewis and his team started evaluating their options. It was then that he received an unexpected call from a veteran officer with B.C.’s Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit.

Staff Sergeant Dan Holt is an expert in tracking and surveilling suspects in rugged and remote environments. He’s been with the B.C. anti-organized crime agency for nearly two decades and has also spent 44 years in the British and Canadian militaries. He was calling to offer his help.

He told Insp. Lewis that he could help track which way the suspects went after they torched their vehicle. Open to new ideas, the search commander accepted his offer and Staff Sgt. Holt packed his black Ford pickup for the long drive to Manitoba.

The sun sets over Provincial Road 290 at the ditch where the suspects' burned SUV was found.

When he arrived in Gillam, a week had passed since the Beardys found the burnt SUV, which had belonged to murder victim Mr. Dyck.

Before arriving near Bird, Mr. McLeod and Mr. Schmegelsky had been spotted numerous times as they travelled across the country, not yet declared homicide suspects. The SUV they were driving was stuck on a trail in Cold Lake, Alta., and a resident helped free them. They were caught on a video camera shopping in Meadow Lake, Sask., and spotted gassing up in Split Lake, Man., where they asked the cashier whether they could buy booze in the dry Indigenous community.

But their trail had seemingly gone cold near Bird. With no sign of the fugitives anywhere in the country, the Manitoba Mounties developed a new theory about their whereabouts. Maybe Mr. McLeod and Mr. Schmegelsky never left the area and instead plunged into the woods near Sundance Creek, not realizing the challenging terrain and weather they were about to encounter.

The woods here are unlike those of Southern Canada. Within moments of stepping in, you’re swallowed by trees, sand flies and mosquitoes. It’s hard to see much beyond a few steps. At times, the ground is boggy and there are scant defined trails. One misstep and you’ll be knee-deep in muskeg or clay near the river.

For the first few days, the B.C. fugitives would have enjoyed warm, dry weather. Then the temperature dropped from a high of 30 C in the day to the low teens with a biting rain. “Those woods are ferocious,” says Insp. Lewis, who was recently promoted to superintendent of Manitoba North. “It was going to be very tough for them to stay alive in those woods for any extreme length of time. Even a week would be very difficult.”

The decision early in the second week of the manhunt to refocus the search on the area surrounding the burnt SUV had been fruitful. On July 29, police discovered several items belonging to the suspects in the Sundance area, including hundreds of rounds of ammunition. They kept searching, but it took a few days before the next big find.

Meticulous and philosophical, Staff Sgt. Holt, or “Tracker Dan,” as he became known in the field, located key evidence on Aug. 1 in the bush near Sundance Creek, when a new search commander, Inspector Leon Fiedler, arrived to relieve Insp. Lewis, who was headed on a family vacation. The tracker found Mr. McLeod’s backpack, clothing and wallet with the teen’s identification inside. In the backpack, there was a full box of ammunition.

The police finally had items directly linked to the suspects, says Insp. Fiedler, a 27-year veteran of the RCMP and a critical incident commander in the Mounties’ Alberta division. “If it wasn’t for him, we wouldn’t have found that evidence,” he says of Staff Sgt. Holt, explaining how he scoured the woods for the tiniest of details, looking for signs of somebody passing through. He did so under the protection of tactical officers who trekked with him, assault rifles at the ready in case the fugitives were still alive and armed. He also had help from a B.C. emergency-response member who also had some tracking experience.

Police believe the murder suspects were unloading weight as they ran through the woods. As more evidence linked to the pair was discovered, including the licence plate of the SUV belonging to Mr. Dyck, a previously announced scale-back of the manhunt never really happened. About 30 officers were on the ground and the RCMP’s infrared-equipped helicopter was brought in from Alberta to help scan the shoreline and woods.

While the Mounties were making headway, news of their discoveries was kept under wraps until a wrecked rowboat was found on Aug. 2 in an eddy of the Nelson River, past the Lower Limestone Rapids. That day would prove to be a turning point, as a cascade of events led police to find evidence connected to the fugitives, as well as some items that likely weren’t.

It started with river guide Clint Sawchuk. He was cruising on the Nelson River, taking a group of tourists to the national historic site of York Factory, when he spotted a blue sleeping bag in the water, tangled up in some willows near Hudson Bay. He notified the RCMP, which sent its helicopter to have a look. While flying to the reported location, officers spotted other items closer to their targeted search area, along with the rowboat (police would eventually come to believe the suspects had never used it).

There are only two or three people who can navigate that treacherous stretch of the Nelson by boat: Billy Beardy is one of them. He was at work in Bird when he received a call in the afternoon, asking if he could take the RCMP on the Nelson River in a jet boat to recover the items spotted from the air.

The trip wouldn’t be easy. The items – another blue sleeping bag and a black backpack – were found below a high cliff and near the big rapids. The water moves fast there and Mr. Beardy had to devise a safety plan. “If your boat actually stops in that area, you’re pretty much a goner,” Mr. Beardy says. “You got maybe 8 to 10 foot swells there,” he adds. “It’s pretty dangerous if you don’t know what you are doing.”

The other potential danger was the murder suspects. Tactical officers offered firepower protection and a helicopter kept watch overhead.

An RCMP helicopter watches the banks of the Nelson River near where the dive team is searching.

In a provincial government jet boat, Mr. Beardy guided the police safely to the evidence. He didn’t see what was in the backpack, but he heard it contained toiletries, including a razor and shampoo. They and the sleeping bag had belonged to Mr. Dyck, police later disclosed. “I was glad that I was there because I knew [the suspects] were there” in the bush, he says.

As Mr. Beardy became more involved in the search – taking an RCMP dive team on the river two days later – his wife grew increasingly worried about his safety. What if the fugitives were still alive and looking for one last showdown with the police? “You have young kids to worry about,” she kept telling him, in tears one day. “You have a lot at stake, too. Not just them.”

The potential danger he was in and the risks he took only hit him afterward. “I was sitting out there like a sitting duck, no armour, with my work jacket on,” he says. “I could have been killed at any time.”

Upon reflection, Mr. Beardy wishes he had the same armoured protections the RCMP had. Listen to him speak about his concerns for his safety during the search.

The Globe and Mail

It had been 12 days since police began their manhunt around Sundance Creek, and despite finding evidence of the fugitives, Insp. Fiedler was considering winding down the search.

Manitoba RCMP officers believed the men could not have survived and there was a good chance their bodies would never be found. Predators such as bears and wolves may have gotten to them. Or they could have drowned in the Nelson River and been swept to Hudson Bay.

He had planned to remove most of his team on Aug. 7, and he was scheduled to return to Edmonton later that day. But before calling it quits, he had one last spot that required further searching. He sent a team to the area where the sleeping bag and backpack had been found five days earlier.

“We really did not want to leave there without giving some kind of sense of closure for the community,” he says. “That’s why we kept pushing as long as we did.”

That morning, the RCMP turned to Mr. Beardy again to take three officers and the tracker back on the Nelson River. They set off just after 9 a.m.

The officers weren’t sure exactly where the sleeping bag and backpack had been found, but Mr. Beardy remembered the spot. He powered down the jet boat as they approached the rapids, but they were still moving quickly in the fast-flowing water, giving them only split seconds to scan the shoreline.

That’s when Mr. Beardy noticed a raven jump up from the brush. “Did you see that?” he asked the officer behind him.

Mr. Beardy spun the boat around and headed toward where the raven had been. A lifelong hunter, he knew the bird could be scavenging on something.

“As soon as we got to the shore, sure enough, we saw them,” Mr. Beardy says.

At first, they could only see one of the fugitives in the sloped thick brush, Mr. McLeod. An RCMP officer scrambled out of the boat and raised his gun. Mr. McLeod was bearded, dressed in a camouflage top and black rain pants, Mr. Beardy recalls. Mr. Schmegelsky was found about 1 1/2 metres away, lower down on the slope. He was dressed in full camouflage. Their bodies, two SKS semi-automatic rifles and a video camera lay about 8 km from the torched SUV. The rifles had been used in the killings.

B.C. RCMP released these photos of the SKS rifles found with the fugitives' bodies.

Police believe Mr. McLeod shot his friend before shooting himself in a suicide pact. The pair talked about doing so in one of six videos recorded on Mr. Dyck’s digital camera. They also admitted to committing the three murders, showing no remorse. In their first recording, Mr. Schmegelsky spoke of an outlandish plan to march to Hudson Bay and hijack a boat to escape to Europe or Africa. In another, he warned they planned to kill more people and expected to be dead themselves in a week.

Police don’t know when exactly the videos were made or why the men killed Mr. Fowler, Ms. Deese and Mr. Dyck. Nor do they know how long the pair had been dead in the brush by the Nelson River, but believe they had been alive for at least a few days and had possibly become trapped, unable to cross the treacherous water and unable to climb back up the embankment.

Detail

MANITOBA

280

290

Gillam

0

12

KM

Suspects’ burned-

out vehicle found

Sleeping bag and

backpack found

near here

Suspected route

the fugitives hiked

Provincial Rd 290

Nelson River

Bodies found

ATV trail

0

2

KM

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

GOOGLE EARTH; MANITOBA RCMP

Detail

MANITOBA

280

290

Gillam

0

12

KM

Suspects’ burned-

out vehicle found

Sleeping bag and

backpack found

near here

Suspected route

the fugitives hiked

Provincial Rd 290

Nelson River

Bodies found

ATV trail

0

2

KM

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

GOOGLE EARTH; MANITOBA RCMP

MANITOBA

Detail

280

290

Gillam

0

12

KM

Suspects’ burned-

out vehicle found

Suspected route

the fugitives hiked

Provincial Rd 290

Nelson River

Sleeping bag

and backpack

found near here

Bodies found

ATV trail

0

2

KM

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: GOOGLE EARTH; MANITOBA RCMP

The wooded area where the bodies were found, with the raven's help.

A chilly mid-August air hovered over Fox Lake residents as they gathered for a cleansing ceremony at the spot where the B.C. fugitives had set their SUV on fire. Several men began by building a fire on the sooty gravel road and participants formed a circle around the flames to share how the manhunt had affected them and shattered their sense of security.

During the two-week search, many residents in Bird and Gillam had been too scared to stray far from their homes or let their children play alone outside. Some struggled to sleep at night and kept hunting rifles next to their beds in case the fugitives made a sudden bolt for their isolated communities.

For some Fox Lake band members, the flood of outsiders – including the police and media – triggered painful memories of historical traumas.

The discovery of the murder suspects’ bodies brought great relief to the residents of Fox Lake and Gillam, but a pall lingered, even over the Beardys.

The time had come to wipe away the negative forces that had descended on their land and to reclaim authorship of the story from the two B.C. fugitives who drove to a dead-end road and then seemingly vanished into the wilderness.

Until a raven appeared.

CREDITS • PHOTOGRAPHY AND VIDEO: MELISSA TAIT • GRAPHICS: MURAT YÜKSELIR • VIDEO EDITING: TIMOTHY MOORE • STORY EDITING: LISAN JUTRAS • DIGITAL DESIGN: EVAN ANNETT

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Renata D’Aliesio

Renata D’Aliesio