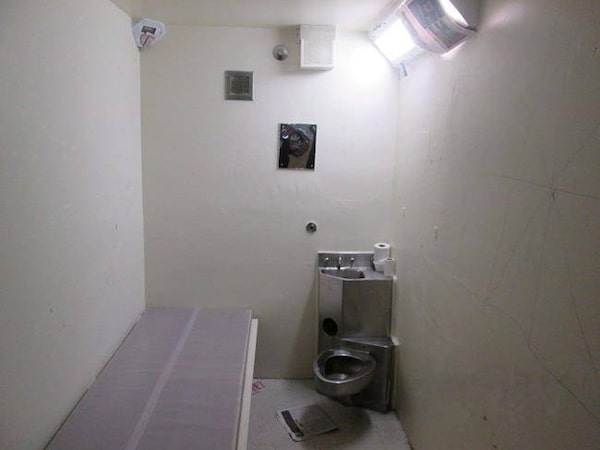

A solitary confinement cell is shown in a handout photo from the Office of the Correctional Investigator.The Canadian Press

Canada’s top court has agreed to hear arguments on the constitutionality of prolonged solitary confinement, setting up a final showdown in a years-long legal push to ban isolation practices in federal prisons.

On Thursday, the Supreme Court of Canada granted several applications to appeal and cross-appeal in two cases that have been winding through lower courts in British Columbia and Ontario. The Supreme Court will hear the cases in tandem. While no date has been set for a hearing, they generally take place seven to eight months after a leave to appeal has been granted.

Launched by the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association and the John Howard Society of Canada in B.C., and the Canadian Civil Liberties Association in Ontario, the cases used many similar arguments concerning the uses and abuses of solitary confinement, also known as administrative segregation.

“It is disappointing that the federal government continues to fight for the right to keep prisoners in prolonged solitary confinement,” said Michael Rosenberg, co-counsel for the CCLA. “The courts have held that this is cruel and unusual treatment. The CCLA hopes that the Supreme Court of Canada will strongly condemn the practices at issue and expand the holdings in the courts below to better protect inmates with mental illness.”

The United Nations has defined solitary confinement as isolation in a single cell for 22 or more hours a day without “meaningful human contact” and prolonged solitary confinement as a period of isolation exceeding 15 consecutive days.

The decision is the latest development in an effort to curtail solitary confinement that was prompted by the deaths of Ashley Smith, who spent more than 1,000 days in isolation, Edward Snowshoe, who killed himself after 162 in segregation, and other prisoners. The Globe and Mail has reported extensively on the prevalence and effects of solitary confinement, beginning with a 2014 investigation into the death of Mr. Snowshoe.

Since 2017, lower courts in both provinces have found various aspects of the current law governing administrative segregation to be unconstitutional. In October, 2018, the federal government tried to sidestep those rulings with a bill that proposed changing the name of administrative segregation to “structured living” and increasing the minimum time that prisoners could leave their cells to four hours from two.

Passed last year, Bill C-83 was widely panned in prison law circles. In a letter to Ottawa, more than 100 lawyers and academics argued that it authorized “solitary confinement under another name” and ignored lower court orders to adopt binding independent oversight and a 15-day limit on placements in isolation.

“The major concerns we stated in the letter have never been addressed,” said one of the signatories, Adelina Iftene, an associate professor with the Schulich School of Law at Dalhousie University in Halifax. “You can imagine a situation where someone could spend 15 years of their life on this unit rather than 15 days.”

Dr. Iftene said she hopes the Supreme Court’s eventual decision will also evaluate the new law’s constitutionality.

A spokeswoman for Public Safety Minister Bill Blair said Ottawa is appealing both rulings because of potential broader impacts.

“It is important to have clarity in the law, which is why Canada is appealing the CCLA and BCCLA decisions to the Supreme Court of Canada,” press secretary Mary-Liz Power said. The amendments made under C-83 put an emphasis on prisoner health and come with a commitment of $448-million toward new staff, infrastructure and mental-health care.

Correctional Service Canada has also appointed University of Toronto criminologist Anthony Doob to head a panel that will monitor implementation.

Last April, Ontario’s appeals court sided with the CCLA in a landmark ruling that placed a hard limit of 15 days on placements in solitary confinement. Anything more, the court declared, constituted cruel and unusual punishment, a violation of Section 12 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The ruling overturned a lower court finding that solitary confinement could cause serious psychological harm to inmates, but that those harms were mitigated by existing laws requiring the close monitoring of prisoner health.

The three-judge appeals panel disagreed, stating that legislative safeguards “are inadequate to avoid the risk of harm.”

Within days, the federal government applied for leave to appeal the decision before the Supreme Court.

The CCLA was less successful in seeking a prohibition on placing mentally ill inmates in segregation before the lower court. It subsequently filed a cross-appeal that will form part of the case before the Supreme Court.

In the BCCLA case, the lower court agreed that federal laws governing solitary violate the charter because they allow indefinite placements without any sort of independent review process. However, the court declined to impose a hard limit on the duration of a solitary placement.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Patrick White

Patrick White