Photo illustration by Katy Lemay

The vaults of the Bank of Canada contained about four times as much cash as usual.

Thirteen thousand troops were on standby.

Jean Chrétien’s most important cabinet ministers had been ordered to remain in Ottawa and were gathered at 24 Sussex Dr. to watch the clock.

As midnight approached in Toronto, key figures in Ontario’s provincial government huddled in a war room stocked with a week’s worth of supplies, and bankers commandeered boardrooms high above the city to monitor ATMs in Australia.

On Dec. 31, 1999, Canadian leaders were preparing for the possibility that civilization would break down. The fear that electricity, phone lines and the financial industry could freeze up at the stroke of midnight because of a simple coding glitch in the world’s computers had come to be known as Y2K.

Michael Guerriere, who ran one of Toronto’s most important hospitals, prepared like a doctor: He went to bed early.

The executive vice-president of the massive University Health Network had spent much of the previous two years working toward this moment. With a growing sense of astonishment and dread, he had been building an inventory of hospital equipment that was computerized and therefore potentially vulnerable to the millennium bug – tens of thousands of devices in total. “It just mushroomed,” he said.

On the 31st, Mr. Guerriere made final arrangements, scheduling extra nurses and doctors to work the overnight shift, before his head hit the pillow around 10 p.m. The next thing he remembers is his bed shaking. It felt, he said, like something had blown up. He jumped to his feet and called the hospital, wondering if the world’s worst fears had come to pass – power systems down, banks unable to dispense cash, phones dead, civil unrest.

Instead, he was given the all-clear. “It was: ‘Everything is fine. Night was uneventful.’ ”

What Mr. Guerriere had experienced, he later learned, were the distant tremors of a powerful earthquake that struck Quebec’s Lake Kipawa early on the morning of Jan. 1.

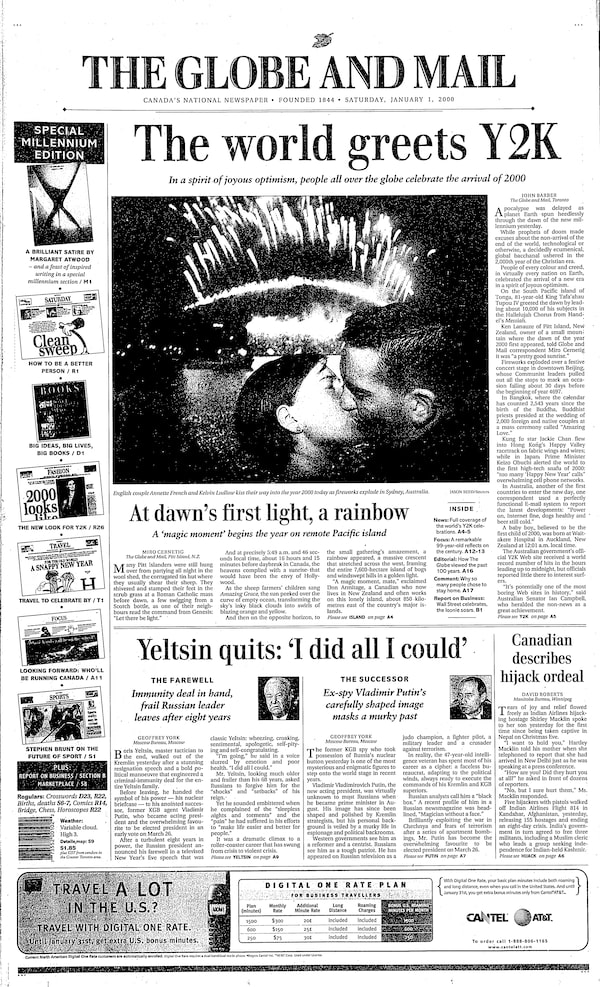

The Globe and Mail's front page from Jan. 1, 2000, notes that 'apocalypse was delayed as planet Earth spun heedlessly through the dawn of the new millennium' the night before.Globe and Mail archives

For those who felt it, the quake was the last jolt of fear and excitement before the setting in of a vast, global sense of anticlimax. As the year 2000 dawned from Wellington to Honolulu, and the planet’s digital infrastructure held more or less steady, hundreds of millions of people were left wondering what the scare had been about.

One credible estimate put the worldwide cost of addressing Y2K at US$600-billion – roughly what the U.S. spent fighting the war in Vietnam. Had it all been a scam? A collective delusion? A punchline?

Twenty years later, that time looks more like the beginning of something than the anticlimactic end. Interviews with dozens of people who were on the front lines of busting the bug and thousands of internal government documents make it clear that Y2K, while occasionally overblown, was more real and more dangerous than is commonly understood.

And today, fear of rogue computers doesn’t seem so paranoid after all. From the vantage point of 2019, in a world where algorithms have helped elect a frightening new kind of politician, the computers in our pockets have begun rewiring our neural networks and our lives online are more closely monitored by governments and corporations than ever before, the anxiety of those years can seem downright prescient.

On Jan. 1, 2000, the troops started standing down, the bureaucrats emerged from their war rooms, and the bankers breathed a sigh of relief. It seemed like nothing had happened.

But something had happened. We had come face to face with the fact that our civilization rests on a thin bed of silicon – and we didn’t like what we saw.

Peter de Jager of Brampton, Ont., was an IT consultant who mobilized the world to take the risks of Y2K seriously.Edward Regan/Edward Regan/The Globe and Mail

‘Tick tock … tick tock’

Peter de Jager wasn’t famous yet when, in 1993, he took the stage at a wonky systems-management conference in San Francisco to talk about the so-called PC productivity paradox – the odd-seeming fact that the widespread adoption of personal computers had not made the economy more productive.

Back then, he was still just a shaggy, bearded IT consultant from Brampton, Ont., with a preference for loud ties and an unplaceable accent.

But when an editor from Computerworld magazine approached him after his talk to ask if he would write an article about it, Mr. de Jager made a counteroffer that would change his life.

“I said, ‘Let me write about a real problem.’ ”

The resulting three-page spread in the influential weekly was titled, simply, “Doomsday 2000.” In prose that oscillated between the dryly technical and the apocalyptic, Mr. de Jager laid out a simple bug. Most of the world’s computer programs were coded to read years with two digits instead of four, so “93” instead of 1993. The shorthand was designed to save scarce memory space in the early days of computing, and it made sense at the time. But when the date ticked over to Jan. 1, 2000, a lot of software would become confused. It would think the year was 1900, or not know what to think. Some unknowable percentage of the world’s computers would malfunction, either by making errors or simply crashing.

“The crisis is very real,” he wrote.

A computer terminal at The Globe's newsroom shows the login page of its electronic publishing tool, then called InfoGlobe, in 1988.Jeff Wasserman/Jeff Wasserman/The Globe and Mail

He wasn’t the first to notice the problem. Programmers had long understood the compromise they were making, but had figured that their dashed-off code would be extinct by the new millennium. Instead, it became a renovated, tar-papered mess at the heart of computer systems that ran the world. This was a problem, and an expensive one: As far back as 1987, the New York Stock Exchange had spent US$29-million and enlisted a team of 100 coders to pre-empt Y2K problems.

Mainstream awareness was another matter, and when Mr. de Jager published “Doomsday 2000” it was virtually nil. With his “gift of the gab,” bequeathed by a part-Irish heritage, Mr. de Jager was well-suited to changing that. He could hold an audience with a deep, urgent voice and the ability to put things in the starkest possible terms – somewhat, colleagues would later observe, like a travelling preacher.

Such a skill set was particularly valuable given the bafflement and paranoia that computers tended to inspire at the time.

The idea that “code” could give instructions that would make machines calculate or type or even beat the world’s best chess player – as IBM’s Deep Blue had done in 1997 – was hard to accept for most people, even as it became the animating process behind much of the developed world’s infrastructure.

Nicholas Zvegintzov, a software consultant who would go on to spar with Mr. de Jager over the issue of Y2K, says the millennium bug resonated with people in part because they fundamentally felt that computers were “magic.”

"If you’re teaching civil engineering, you have to actually build bridges. But with software there’s nothing to latch onto,” he said.

Programmers at IBM's Japanese offices work in 1998 on Y2K preparedness at a centre dedicated to that purpose.Koji Sasahara/Koji Sasahara/The Associated Press

As popular awareness of Y2K expanded – an episode of 60 Minutes made a particular splash – Mr. de Jager embraced the role of millennium guru. His speaking fee at conferences and corporate retreats rose to US$10,000 a speech; his wife began to keep track of daily media interviews in an Excel spreadsheet. He slapped a Y2K vanity plate on his Ford Explorer and often wore a tie adorned with pictures of clocks, the better to send the message: Time is ticking.

But even with messengers as obsessive as Mr. de Jager, a sea change in attitudes came slowly. By the fall of 1997, just 9 per cent of Canadian businesses had a formal plan for tackling Y2K.

Maurice Baril, then Canada’s chief of defence staff, initially thought his technical staff were playing a prank. “I can remember the first time I heard of it, in a kind of classified report; it was just me and the deputy minister in a small room. I said, ‘When you’re finished joking, please tell me what your briefing is about.’ ”

Such briefings were no joke, however – and would increasingly come to dominate the work of government. It didn’t take long for David Robert Loblaw to learn that. A lean man with close-cropped hair, and a taste for black turtlenecks, Mr. Loblaw got a job in 1992 working on the computer systems of Human Resources Development Canada, the department that sent out unemployment-insurance cheques.

It was an exciting time for techies. Software was already big business but still shot through with a hacker subversiveness and traces of a California idealism that nourished the early industry. Mr. Loblaw was intoxicated by the growing potential of computer networks, especially the precursors of the internet. He remembers gazing at a five-inch screen with blue text and a flashing white icon, and gushing: “Look, I’m connected to a library in Finland!”

Not everyone shared his enthusiasm. PCs were still treated by many of his colleagues as an annoyance, if not a threat. Mr. Loblaw’s boss was so uneasy with e-mail that she printed out all of her digital correspondence and stored the messages in tall metal filing cabinets lining the walls of her office.

As the federal government began addressing Y2K in the late 1990s, Mr. Loblaw shifted his focus. His job had been a thrill, with top-of-the-line computer equipment at his fingertips and interesting programming challenges around every corner, he said. “And then it all stopped.”

Before long, Mr. Loblaw was allowed to work on one thing only: the bug.

Globe and Mail news stories from 1998 and 1999 report on the upcoming Y2K menace.Globe and Mail archives

‘An army of programmers’

By the mid-1990s, Y2K anxiety had gone global. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development issued stern reports about global preparedness, and mass-circulation outlets such as Newsweek started printing cover stories forecasting, “The day the world shuts down.”

Media coverage had a galvanizing effect on senior figures in the Canadian government, such as Peter Harder, then secretary of the Treasury Board. “I was reading a piece in The New York Times, and I thought: ”Holy shit,” he said.

Different countries prepared after their fashion. China ordered airline executives to fly on Jan. 1 as an incentive to get repairs done on time. The cautious Dutch central bank announced that future credit approvals would be tied to Y2K-readiness. U.S. President Bill Clinton summoned elderly computer programmers out of retirement, not unlike Churchill enlisting fishing boats for the evacuation of Dunkirk.

Big business also revved to life. In February, 1998, a Canadian task force of senior corporate executives, chaired by the president of BCE Inc., gave a blunt warning on the risks of Y2K. “The Year 2000 date code problem poses a real threat to the profitability of Canadian firms,” they wrote. “In some cases, it will even mean business failure.”

The bug was particularly terrifying for financial institutions. The five major Canadian banks publicly announced Y2K budgets of about $120-million each, as they envisioned a cascade of computer failures destroying consumer faith in their competence.

“It was existential in scale,” said Michael Foulkes, then TD Bank’s chief information officer. “At the time it was the single largest priority and the single largest project.”

University of Manitoba student Bryan Meyer demonstrates Y2K preparedness measures for small business to then-Industry Minister John Manley, left; CIBC president Holger Kluge, middle; and Winnipeg businessman Bill Scurfield.Canada News Wire/Canada News Wire

During those years, Mr. de Jager went on lucrative barnstorming tours around the world. In 1998 alone, he earned US$1.5-million. He testified before the U.S. Congress and Canadian Parliament, lectured a conclave of central bankers in Switzerland, and was invited to the World Economic Forum. The web domain www.year2000.com, which he co-owned, received a reported 600,000 visitors a month. “I was famous, there’s no doubt about that,” he said. “I couldn’t go anywhere in the world without someone recognizing me. There was one point that there were four TV crews sitting outside my house.”

Sometimes Mr. de Jager’s passion for the Y2K mission veered into hyperbole. “This is the biggest story in the history of mankind, barring world war,” he told the Financial Post Magazine.

But when the setting called for it, Mr. de Jager could also be chillingly sober and factual, laying out the scope of the problem, the deadline and the likely cost, before watching managers and bureaucrats turn white in their chairs.

In the late winter of 1998, Ottawa’s standing committee on industry invited Mr. de Jager to speak about the bug, and he came armed with bracing statistics. The federal government completed projects on schedule just 16 per cent of the time, he said. And while Ottawa had already earmarked $1-billion, companies routinely underestimated their Y2K costs by a factor of five.

Mr. de Jager’s presentation lit a fire under the Canadian bureaucracy, said Susan Wild, who worked on Y2K issues for Environment Canada. “There was this Cassandra going around saying the sky is falling and he freaked everyone out enough that they said, ‘Let’s take a closer look at this,’ ” she recalled. “He may have gone overboard, but that’s what people react to, right?”

The Treasury Board had recently assembled a crack team to investigate Y2K readiness in the federal government, recruiting the long-time IT managers Hy Braiter and Grant Westcott in the most solemn terms. “They appealed to my sense of loyalty to the country,” Mr. Braiter recalled.

Researching their report was an education in how wired government had become. Mr. Westcott was struck by the computer-dependency of military machinery such as tanks and fighter planes. Mr. Braiter was shocked to learn about computer chips embedded in the refrigeration system that kept dangerous bacteria frozen in government labs.

“At one meeting, someone swore me to secrecy or else they would have to shoot me. I visited Corrections and wondered if the prison cells would all open at once. Those were the kind of things we joked about. But we didn’t know,” Mr. Braiter said. “It came down to, ‘Is there going to be a real fiasco? Are planes going to fall out of the sky, are terrible viruses going to be let loose in the air? Could a nuclear reactor do something? … You start to wonder, is it going to be dark in New York City?”

As the men got down to work, Quebec was hit by a historically brutal ice storm. For a week at the height of winter, more than a million people in Southern Quebec and Eastern Ontario were without power after sheaths of ice brought down power lines and transmission towers. Thirty-five people died. The men wondered if they were watching a preview of things to come.

“In some respects,“ Mr. Westcott said, “we thought that was prescient.”

Downed power lines lie near St. Bruno, Que., after the great ice storm of 1998.Jacques Boissinot/The Canadian Press/The Canadian Press

By February, they had compiled some terrifying possible consequences for the Canadian government: failure to pay out the Canada Pension Plan and Employment Insurance; “inability to manage border crossings”; “inability to collect taxes”; “inability to forecast weather”; “health and safety risks from laboratory failures.” In essence, a total government collapse. “Eliminate all competing priorities” they warned. Y2K would have to be the “top” systems project until the year 2000.

After Mr. Braiter’s presentation to a room full of worried-looking cabinet ministers, Mr. Chrétien said, “‘You heard the man: make sure you do it.’” By summer, department heads were receiving letters from the prime minister informing them that “all other business is secondary.”

It was “almost like a wartime initiative,” Mr. Braiter remembered. “All hands to the deck.”

For the next 18 months, any new law or government program had to be assessed for how it might interfere with the Y2K effort. Not much passed muster. Some departments effectively went on auto-pilot. Mr. Westcott called them “the lost two years.”

If the rest of government geared down, its computer work entered overdrive. According to one final count, 11,000 people would ultimately toil on the federal government’s computer systems during the Y2K project.

The work was dull and often a little farcical. Many “legacy systems” were written in outdated coding languages that had become the equivalent of Aramaic. And because so much of the software had been programmed in-house, it wasn’t always possible to anticipate where problems would lurk without reading every line of code.

To Mr. Loblaw, it was the worst kind of drudgery.

“It was like, ‘Your job is taking the Encyclopedia Britannica and you have six months to circle all the Es,’ ” he said.

Disillusioned and increasingly convinced that Y2K was a waste of time and money, Mr. Loblaw created an anonymous website in his spare time. He called it the Year 2000 Computer Bug Hoax and bought the url www.justanumber.com.

Soon, he was receiving dozens of e-mails a day from both sides of the increasingly vicious debate about what to make of the date change. One skeptic wrote that he hoped to “hunt these fear-mongers down,” imprison them in tiny metal bunkers and “force them to actually put their worm-farming techniques to good use.“ A preacher from South Carolina who was saying that Y2K would usher in the Biblical millennium told Mr. Loblaw the blood of Christ would be on him and his family forever.

Meanwhile, in the trenches, minor glitches were already starting to crop up in systems around the world, as software projected ahead to the year 2000 and encountered those baffling numbers: 00.

The computers at soap and cosmetics manufacturer Amway rejected a batch of chemicals because they took it to be more than 100 years old, Mr. de Jager explained in yet another magazine article; and a Minnesota centenarian named Mary Bandar, born in 1888, received an automated invitation to enroll in kindergarten.

NORAD missile commanders confirm a launch warning over the phone during a practice drill at the Cheyenne Mountain complex in Colorado Springs, Colo., on Nov. 9, 1999. Some of the most far-fetched Y2K scenarios included malfunctions in NORAD's missile-tracking systems or even accidental missile launches.MARK LEFFINGWELL/AFP via Getty Images/AFP/Getty Images

‘Chuck is getting nervous’

Preparing for Y2K meant doing two things at the same time: trying to fix the date problems in your computer systems, and laying plans for what might happen if you failed.

By the summer of 1999, the focus in the halls of power had shifted from the first to the second – a change signalled, in true bureaucratic style, by the renaming of the relevant steering committee: it would now be focused on Year 2000 Contingency Planning.

One of the terrifying things about Y2K was that a single failure could sow chaos everywhere. Even insiders such as Richard Fadden, then assistant secretary to the Treasury Board, found that it made Canadian peace and prosperity feel suddenly tenuous. His briefings emphasized how computer-dependent the national transportation system was, for example. If a failure stalled trains, trucks, boats or planes, it could quickly start affecting fuel and food supplies.

“By the time we had come to grips with how utterly pervasive were computer systems, it was a shock,” he said. “You had varying views of how serious the calamity might be.”

A man in Seoul leaves a store on Dec. 27, 1999, with a Y2K kit including dried and canned food, candles, matches and butane gas containers. The kits cost US$75 each.Ahn Young-joon/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

Embedded computer chips were responsible for much of this uncertainty. The Gartner Group, a consulting firm, estimated that up to 40 billion such chips existed worldwide, in technologies ranging from nuclear power plants to sewage treatment facilities to microwaves to cars.

The idea that something as ethereal as computer code could cause something as material as a car to malfunction made people skittish, and encouraged stockpiling.

The Canadian Mint received a financial boost when demand for gold and silver coins shot up.

In preparation for a possible run on ATMs, the Bank of Canada increased its inventories of cash to $23-billion, about four times the usual amount. Even that mountain of paper didn’t placate everyone. In April, 1999, a staffer named Gerry Gaetz got a fretful e-mail from a colleague about a recent conversation with the bank’s deputy governor Charles Freedman. “We talked about the banknote order and whether the additional order would be enough,” it read. “Chuck is getting nervous.”

Even the supply of fuel did not always look like a sure thing. In 1998, the National Energy Board warned that the shutdown of computerized pipeline safety systems could cause a serious “loss of energy supply” to Canadians.

As the date change grew closer, the NEB made contingency plans for every kind of Y2K failure, from loss of electricity to a halt in postal service. These kinds of plans were becoming common. The federal government briefly contemplated handwriting all the millions of pension and welfare cheques it sent out electronically every month. The Communications Security Establishment, one of Canada’s spy agencies, considered the possible consequences for Stone Ghost, the classified intelligence sharing system. The CBC stationed two people at a remote Saskatchewan transmitter site equipped with a fallout shelter, where they could broadcast instructions for survival.

Across the country, governments projected an unreadable combination of calm and fear.

Industry Canada had an awareness campaign called “SOS 2000,” which released a TV ad warning that Y2K could “sink your business” over simulated footage of a boat approaching an iceberg. Government Computer magazine published a cover image of a meteor streaking across the sky with the headline, “One Year To Impact.” In December, 1999, Ontario Hydro announced that there wouldn’t be any problems – but suggested people stockpile food, water and cash.

Major Rod Matheson briefs his troops at the command centre of Operation Abacus, the military task force created to deal with Y2K, in Ottawa on Dec. 31, 1999.Dave Chan/The Globe and Mail/The Globe and Mail

‘This is Op Abacus’

If disaster struck, the army was ready. The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) was given a budget of more than $350-million to prepare for Y2K. In a clever nod to fears of technological collapse, they called the mission Operation Abacus.

Some in the CAF took a tongue-in-cheek approach, purchasing little wooden abacuses as keepsakes, but senior military brass threw themselves at the undertaking with deep earnestness.

Military planning was fuelled by memories of the Quebec ice storm. “Personally I was very afraid of a big community losing its power grid,” said Mr. Baril, chief of the defence staff at the time. “We were afraid of the survival of our people if the systems broke down.”

The forces spared no effort. According to internal documents and public testimony from senior officers, the CAF had assembled a daunting group to get the country back on its feet after the Year 2000: 1,500 headquarters staff in Ottawa, about 13,000 troops across the country, and fully 50 per cent of the country’s primary reservists if they were needed, along with helicopter squadrons and ships at sea.

Abacus troops were expected to be self-sufficient for 30 days after the millennium, so the military stockpiled critical supplies at depots in Montreal and Edmonton – water purification units, portable boilers and heaters, military vehicles, individual meal packs, winter clothing – and prepared to provide perimeter security at federal prisons if needed.

Mel Cappe, clerk of the Privy Council, was prepared for possible civil unrest if Y2K-related chaos arrived.Fred Chartrand/The Canadian Press

Mel Cappe, who as clerk of the Privy Council was the most senior bureaucrat in Ottawa, had riots on his mind as December approached. “What happens after the third week without power in the winter? People storm the Parliament buildings,” he said recently.

If the preparations sometimes sounded ominous, most close observers were feeling good about the world’s progress by late 1999.

Even Mr. de Jager believed the problem was basically in hand. The itinerant preacher of the millennium bug was starting to give the all-clear. In a post on his website titled “Doomsday Avoided,” he announced: “We’ve finally broken the back of the Y2K problem.”

It was just as well. Life on the road was wearing on him. That winter, Mr. de Jager almost broke his own back after slipping on some ice in Toronto, putting him in a wheelchair for his flight to Paris that day.

After hobbling up on stage, he faced a final indignity: Someone in the audience stood up in the middle of the presentation and cried, “This is all nonsense!”

Mr. de Jager barely had the energy to respond.

“I was bone tired,” he said. “We’d done our bit. The arrowhead had been released, and it was going to fall where it fell.”

Paul Scott, the Ontario government's Y2K preparedness chief, is shown in the media centre built to monitor for devastating developments. He and his colleagues were locked in the makeshift bunker with emergency supplies as the fateful night approached.Patti Gower/The Globe and Mail

‘Night Watch’

The day of the date rollover was shot through with angst and absurdity. On the afternoon of Dec. 31, Paul Scott, the bureaucrat responsible for the government of Ontario’s Y2K prep, installed himself in a makeshift bunker near Queen’s Park. It was “well stocked with food and all sorts of stuff,” he said. He and his colleagues were prepared to be in there for up to a week. As night approached the doors were locked.

The mint had enough diesel fuel to run generators for a week, extra security on hand and a close eye on the building’s elevators.

Midnight soon began ticking around the planet in little spasms of elation. At 24 Sussex Dr., where Mr. Chrétien had gathered his inner circle, the PM brought out some ancient and very good Scotch once “the sun had risen in New Zealand,” said John Manley, then Industry Minister. (“I think if it had been apocalyptic, we would have needed cheaper Scotch,” he added.) Mr. Cappe was ready to bring the rest of cabinet together if Paris crashed. “I remember watching the fireworks at the Eiffel Tower at midnight,” he said, “and breathing a sigh of relief.”

Canada’s East Coast was next over the parapet. That, too, was uneventful. David Jurkowski, Canadian Armed Forces chief of staff for joint operations, received reports of a reveller in the region firing off a celebratory shotgun blast in his backyard and knocking out power to his own house. “We had to have a good laugh about that,” he said. With the arrival of midnight in Ottawa, the rank-and-file were ready to classify Y2K as a non-event. Channel-surfing soldiers settled on a televised Celine Dion concert to pass the time. Operation Abacus was effectively over, and Mr. Jurkowski’s colleagues couldn’t resist a bit of snickering. “There were a lot of comments of: ‘Well, maybe something will happen on Y3K.’”

Alison Crawford, a CBC reporter in New Brunswick, had been assigned to monitor the Point Lepreau nuclear plant that night, in case it melted down. “When nothing happened, I called my editor,” she said. “And he sent me to a hotel to cover a conga line.”

Revellers in Toronto celebrate New Year's Eve, 1999-2000, on Queen's Quay.Tibor Kolley/The Globe and Mail

By Jan. 1, the rest of the country had joined that proverbial conga line. The scare had passed, and Canada was in the clear. Polling indicated that on the first day of the new year, exactly zero per cent of Canadians were “very concerned” about Y2K hurting them. Tech stocks were expected to have a “relief rally.” Meanwhile, the resilience of Y2K-skeptical countries such as Italy and Japan, which took few precautions and emerged unscathed, was starting to sow doubt about the whole enterprise. There was usually an explanation – many Japanese computers used an alternate imperial date system in which the year 1999 was rendered as Heisei 11, for example – but it was hard to overlook that no one, not even the laggards, was suffering from the bug.

Perhaps because expectations of disaster were so high, the public largely overlooked the myriad glitches that did occur. Some were more serious than others but they suggested, at the very least, that the computer problem was real. The U.S. lost touch with spy satellites for several hours. Britain’s National Health Service sent incorrect Down syndrome test results to more than 150 women, leading to at least two abortions of healthy fetuses. A Japanese nuclear plant lost its radiation alarm system.

If no one had acted in the previous few years, there almost certainly would have been more issues. In its Y2K postmortem, the federal government found that the following government functions would have “failed” without remediation: 22 food inspection systems, the computers that regulate day-to-day immigration approvals, Environment Canada’s ice forecasting software and 18 million lines of code that managed the production of pension and welfare cheques.

“It wasn’t totally a hoax, in that we found stuff!” said Gerry Gaetz of the Bank of Canada.

Said Paul Scott of the Ontario government: “The number of systems that were updated as a result of the project can’t be overestimated.”

Still, even those who lived and breathed the millennium bug continue to grapple with ambivalence about the significance of what happened in those years.

“It’s either the biggest scam that’s ever been pulled on mankind or it’s the most colossal disaster ever averted by mankind,” Mr. Cappe said. “I think it’s a bit of both.”

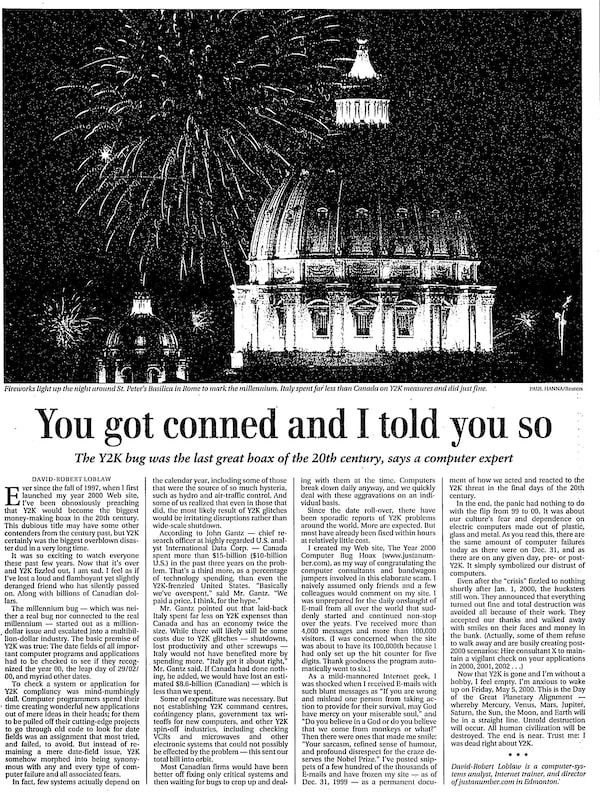

An opinion piece in The Globe from Jan. 6, 2000, mocks the Y2K emergency preparedness movement as a boondoggle.Globe and Mail archives

‘Y2000 degraded environment’

For doubters such as Mr. Loblaw, Jan. 1 felt like a vindication. When there is a chance to say “I told you so” on an international scale, it is hard to resist. He had pitched an article to The Globe and Mail, and in his op-ed published Jan. 6 he outed himself as the creator of the Year 2000 website and jeered Canadians who got “conned.”

“I thought, ‘Nothing happened, so there’s no harm – no fear – in saying my boss is a dumbass,’ ” he recalled.

Mr. Loblaw may have felt that he got Y2K right, but he was dead wrong about the effect of his op-ed. A few days after it was published, he had a weekly phone call with his managers in Ottawa.

“I heard all this murmuring in the background,” Mr. Loblaw said. “Suddenly I realized there were a lot of people in the room. They said they read my article … . My two feeds on my computers were actually terminated as I was speaking.”

His contract with the federal government would not be renewed. Today, he owns a chocolate shop in Regina with his wife, “as far away from computers and technology as I can get,” he said.

For Mr. de Jager, the bad dream began on Jan. 1. He had arranged to fly overnight from Chicago to London, to prove his confidence in the airline industry and air traffic system. The plane touched down at Heathrow without a hitch. But with the meltdown averted, the stock of all things Y2K, Mr. de Jager’s included, was about to plummet.

“Should we all be feeling a bit silly this morning?” a journalist asked him shortly after the date change.

“Why?” he replied, audibly annoyed. “Because we haven't seen problems? You know, I have been doing [interviews] now all day and I keep getting asked the same questions. And it's a rather silly approach.”

From Mr. de Jager’s perspective, he hadn’t gotten anything wrong. Businesses and governments had done what he told them to do. Their efforts were the reason sparks weren’t flying out of the global economy. It wasn’t evidence of a hoax, but mission accomplished.

Virtually no one was convinced.

“In January, we received death threats,” he said. “You know the best thing that could have happened to the Y2K story, the best thing, is for a nuclear power plant to melt down, because of Y2K. It was joked in the industry, over beer and pretzels, ‘We shoulda let one industry fail.’ ”

Mr. de Jager has tried to reinvent himself since that time, with mixed success. His website’s homepage, advertising a “provocative keynote speaker,” makes no mention of his earlier fame. “I stopped giving interviews,” he said. “I was tired of being the subject of articles saying I was a fraud.” (Now, to tell his version of the story, Mr. de Jager is starting a podcast, scheduled to launch in January.)

Peter de Jager in December, 2019: 'I was tired of being the subject of articles saying I was a fraud.'Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail

In the past two decades, the millennium bug has become a kind of byword for fraudulence and hysteria. Conservative politicians across the English-speaking world have invoked our apparent overreaction to Y2K as a way of minimizing concerns about climate change and a no-deal Brexit, both disasters widely predicted by experts.

But for all the pat jokes and cynical arguments, the race to the year 2000 also had a more substantial legacy, shaping both modern tech and how we feel about it.

Hundreds of thousands of coders entered the computer industry to bust the millennium bug. Canadian businesses needed fully 26,000 additional workers to battle Y2K, according to Statistics Canada. Silicon Valley executives successfully lobbied U.S. lawmakers to nearly double the number of skilled-worker visas, from 65,000 to 115,000 a year, to help with the date change problem. Outsourced Y2K work even helped expand India’s IT industry during that time, kickstarting a sector that now directly employs about four million people.

Computer manufacturers were also fuelled to new heights by the sheer bulk of tech purchased in those years to replace bug-bitten machinery. Lou Marcoccio of the Gartner Group (now Gartner Inc.), a U.S. consultancy that helped businesses get ready for Y2K, says that the development of everything from cellphones and laptops to the blockchain technology underlying cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin was accelerated by the Y2K money spigot.

“Year 2000 forced a lot of investment in computing systems in general,” he said. “That whole industry changed considerably, and it had to do with some of the investments they were making.”

That may be the great irony of Y2K. A period of real fear about the power of computers only deepened our dependence on them. Now, two decades later, we are living through another moment of reckoning with that dependence – wondering if it’s healthy, or safe, or sustainable, to vest this much power over our lives in tangles of code that are poorly understood by anyone but their authors.

The usual ambient anxiety about corporate surveillance, shattered attention spans and social isolation – our daily diet in this digital age – has been supplemented with something stronger.

The recent Boeing 737 Max crashes in Indonesia and Ethiopia were found to have been partly caused by a software error that made the planes nosedive shortly after takeoff. U.S. congressional hearings this fall have drawn attention to the misinformation spread on digital platforms such as Facebook that has destabilized democracies around the world. In Nunavut last month a cyberattack froze income-support payments for days, forcing territorial authorities to fax makeshift food vouchers to remote communities where hunger loomed.

Planes falling from the sky; civil unrest; the loss of essential infrastructure – all caused by bugs or otherwise vulnerable code. It sounds a little like Y2K, only 20 years behind schedule.

Illustration by Katy Lemay

Eric Andrew-Gee

Eric Andrew-Gee