Four meatless burger alternatives stacked on a bun are from the bottom: Yves, Lightlife, Unbelievable and Beyond Meat.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Forget those homemade lentil pucks your vegetarian cousin used to bring to family barbecues. From fast-food restaurants to investing strategy sessions, a new wave of high-tech veggie burgers has suddenly become the entrée of choice for both foodies and money managers.

The fake-meat revolution is most evident on Wall Street, where shares of Beyond Meat Inc., purveyor of pea-protein patties, have shot up sixfold since going public in early May. The company’s rise to a multibillion-dollar valuation has burst past all expectations for veggie burgers and similar products. If enthusiasts are right, the still tiny California-based company, with only US$87.9-million in sales last year, could be just the first of several startups to cash in on the growing appetite for artificial beef and similar fare.

“Beyond Meat has completely changed the narrative around plant-based proteins,” says Sylvain Charlebois, a professor at Dalhousie University in Halifax who specializes in food policy. “Bay Street and Wall Street used to regard the agri-food sector as this boring, stuffy business. Then Beyond Meat’s shares exploded in price and suddenly attitudes have turned inside out.”

The biggest reason for that attitude shift is the dawning recognition that a vast new industry could be up for grabs. Unlike earlier veggie burgers, the new brands of fake meats aren’t aimed primarily at vegetarians or health faddists. They are faux flesh intended to appeal to a much wider audience of mainstream consumers – people who enjoy eating beef, pork and chicken, but are trying to cut down on their consumption of animal protein, for health or environmental reasons.

Those occasional vegetarians – flexitarians or reducitarians, in marketing jargon – constitute a sizeable and growing market. Depending on your definition, sales of meatless meats amounted to just over US$1-billion in 2018, says Aswath Damodaran, a professor of finance at New York University and a widely followed authority on stock valuation. That is minuscule compared with an overall meat market worth US$250-billion in the United States alone, and close to a trillion dollars globally, in 2018.

If new varieties of fake meats can carve out a bigger slice of the wider meat market, fortunes are up for grabs. While estimates vary widely, most analysts expect fake meat sales to swell to somewhere between US$5-billion and $8-billion by 2023. For his part, Dr. Damodaran sees the meatless-meat market swelling to US$12-billion over the next decade.

Which companies are best positioned to take a slice of that market? That depends in large part on who wins the race in the lab. Despite the tofu-and-incense vibe around veggie burgers, the emerging stars of the plant-based scene are technology companies that use advanced engineering to mimic real meat.

Their immediate goal is to achieve the holy grail of the fake-meat industry: an artificial burger that can fool even the bloodiest-minded carnivore. Some contenders are getting close. In Canada, A&W outlets have been serving up Beyond Meat burgers for the past year to generally positive response. In the United States, Burger King is rolling out Whoppers that use a rival meat substitute from Impossible Foods Inc. It, too, appears to be receiving a thumbs-up from customers.

Globe and Mail journalists take the meatless taste-testing challenge

Beyond Meat top choice for Wall Street after bullish results

Canada well-positioned to benefit from non-meat alternatives, says Beyond Meat’s Ethan Brown

Established food giants are shouldering their way into the contest. Canada’s own Maple Leaf Foods Inc. has invested US$600-million in acquiring a couple of established vegetarian brands and launching a subsidiary, Greenleaf Foods, devoted to plant-based protein products. It is in the process of constructing a factory in Indiana devoted to turning out veggie burgers, sausages and other delights. Meanwhile, Nestlé SA is introducing its own veggie burger and meat-industry colossus Tyson Foods Inc. is launching a burger that is half pea protein and half Angus beef.

More competition is coming. Dr. Charlebois says plant-based proteins were all the buzz at the food-technology industry’s big convention in New Orleans, La., earlier this month. He figures he tasted at least 25 meatless meatballs, many of them from smaller companies with products that have yet to hit the mass market. Several of those new entries put their big-name competitors in the shade. “By the standards of what I was tasting, I would position Beyond Meat’s product as maybe average,” the food expert says.

The rush of ingenuity into the sector holds the promise of creating a new industry. But it also raises questions about whether the investing frenzy around fake meat is getting ahead of itself. Will a significant portion of the population take to meat engineered in a lab? How much will they pay for the privilege? And, perhaps most important, will the crush of competition in the fake-meat sector erase any potential for profits?

Lightlife burger.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Creating fake meat – at least, fake meat that can fool a discriminating carnivore – isn’t as simple as stirring together bean mash and red dye. Instead, it depends on a complex, highly engineered process. The great paradox of fake meat is that it is an earth-friendly product with absolutely nothing natural about it.

Food scientists are aware of the irony. “A piece of meat is minimally processed,” says Alejandro Marangoni, a professor of food science at the University of Guelph. “You have a cow, you kill the cow, you cut it up into pieces, you’re good to go. But a plant-based process? That involves raising the plants, extracting the protein, drying the protein, mixing it with other ingredients in just the right quantities. It’s a lot of work, a lot of steps.”

The ingredients list for Beyond Meat burgers demonstrates this complexity: It spans more than 20 items including pea, rice and mung-bean proteins, beet juice extract and dollops of canola and coconut oils. And that’s just the start of what is involved in creating a convincing faux burger. “We use a proprietary system that applies heating, cooling and pressure to align plant-based proteins in the same fibrous structures that you’d find in animal proteins,” the company’s website says.

Beyond Meat continues to tweak its product. Its newest burger, which hit grocery shelves this week, claims to be even “meatier” than the original version by mimicking the marbling, or pockets of fat, that help to give real meat its flavour. It also uses apple extract to provide a more meat-like colour experience, in which the patty starts out red and turns brown.

For sheer scientific wizardry, though, Impossible Foods takes the crown. The privately owned California-based company says the key ingredient in meat’s flavour is heme, a naturally occurring iron-rich molecule that helps transport oxygen in plants and animals. What we’re really craving when we want a piece of meat is that heme, according to the folks at Impossible.

To create a vegetarian source of heme, the company uses the heme-containing protein from the roots of soy plants. It takes the DNA from soy plants and inserts it in genetically engineered yeast, which then multiply and produce large amounts of heme. Unless you have a PhD in biochemistry, you don’t want to try this at home.

Even more technological advances are on the way. At the moment, most plant-based meat producers are focused on producing burgers. In part, that is because a hunk of raw hamburger is a soft, pliable mass. The next and more difficult hurdle is creating a vegetarian steak, with the denser, firmer mouth feel of a nice sirloin.

“The more you look at things, the more you realize, boy, a piece of meat is really complicated,” Dr. Marangoni says. Animal flesh is a complicated mix of different tissues that provide not only taste but also structure. Muscle fibres, for instance, help to provide the texture that make a steak so appealing.

His team at the University of Guelph is working on ways to mimic that structure by extruding plant material at high pressure to stretch it and create a texture similar to that of meat. They have already succeeded in producing small amounts of vegetarian meat in the lab that resemble thin, fast-fry steaks. “You fry it up in a bit of oil and people go crazy about it,” Dr. Marangoni says. The next step, he says, will be to prove the process can be scaled up to commercial volumes.

Unbelievable burger.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

The biggest short-term problem for the fake-meat industry is that all that research, technology and processing chews up large amounts of money. Product prices reflect the amount of investment required. At supermarkets in downtown Toronto, a two-pack of plant-based burgers from Greenleaf’s Lightlife line or Beyond Meat sells for $7.99. That is a couple of bucks more than the real meat equivalents.

Despite the lofty prices, plant-based burgers are not yet churning out riches for the people who make them. Beyond Meat lost US$6.6-million in the first quarter of the year on sales of US$40.2-million. Since its start in 2009, it has never made a penny of profit.

Yet, that hasn’t stopped investors from piling in. Since Beyond Meat’s initial public offering (IPO) on May 1, the company’s shares have rocketed from US$25 to US$151.48, making it by far the best-performing Wall Street IPO of the year. The business’s current market capitalization – the total market value of all its shares – stands at a whopping US$9-billion.

To put that another way, the market is saying that Beyond Meat is more valuable than News Corp., the Gap or TripAdvisor. This seems rather debatable. A stock is usually regarded as exuberantly priced if it sells for more than 30 times forecast earnings. Beyond Meat makes a mockery of that metric – it is selling for more than 40 times forecast sales.

Many observers see the valuation on Beyond Meat as beyond reason. Analysts at both J.P. Morgan and Sanford C. Bernstein downgraded the stock to “hold” this week, citing concerns about how far the share price had soared. Dr. Damodaran, the valuation expert, is even more downbeat: He puts fair value for Beyond Meat at only US$47 a share – nearly double its IPO price but only a third of its current market value. It’s impossible at this early point to predict the company’s long-term ability to generate profits, he notes.

But even skeptics who scoff at Beyond Meat’s valuation acknowledge the company appears poised for rapid expansion. Its revenue more than tripled in the first quarter from a year earlier and the company expects to hit US$221-million in sales during 2019. The galloping growth suggests it is tapping into an underserved market for convincing mock meats.

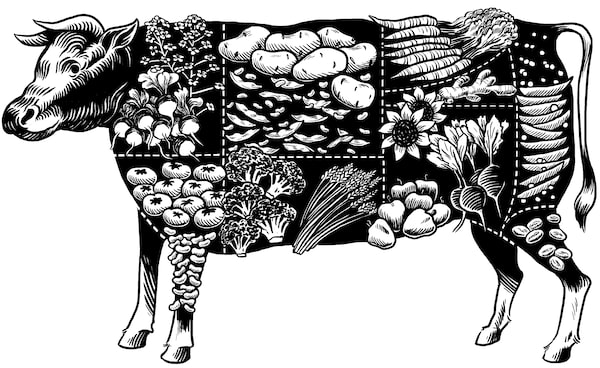

Illustration by Jonathan Dyck/Jonathan Dyck

Consumers’ desire to change how they eat has been apparent for a while, Dr. Charlebois says. A 2018 survey of 1,027 people conducted by researchers at Dalhousie and the University of Guelph found nearly a third of Canadians were thinking of reducing their meat consumption over the next six months. However, nearly half reported they were currently eating meat daily while another 40 per cent consumed it once or twice a week.

The gap between the apparent desire to cut back on meat and actual eating habits may have reflected the lacklustre state of vegetarian alternatives. What has changed over the past year, Dr. Charlebois says, is the ability of companies such as Beyond Meat to “create a bridge between the bloody stuff and the plant-based stuff” with fake meat that offers many of the same satisfactions as the real thing.

“[For] five years there was a demand for a product like this, but there wasn’t a suitable product,” he says. “Now, there is.”

One of the biggest driving forces behind the new interest in plant-based eating is growing evidence that cutting back on meat can improve health. The Canadian Cancer Society urges people to limit red meat and avoid processed meat. A report earlier this year from the Lancet, a peer-reviewed British medical journal, and the Eat Foundation of Sweden recommends a dramatic reduction in global consumption of “unhealthy foods, such as red meat” by at least 50 per cent.

The environmental burden from meat production is also impossible to ignore, especially as the global population grows. The Eat-Lancet commission found agriculture occupies about 40 per cent of land around the world and is responsible for up to 30 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions. The Good Food Institute, a U.S.-based non-profit organization, argues current agricultural methods simply can’t sustain a world population that is expected to swell from 7.6 billion people now to nearly 10 billion by 2050.

Add in concerns about animal welfare – from chickens being raised in confined conditions to cattle dosed with high levels of antibiotics and hormones – and it’s small wonder many consumers are looking to reduce their meat intake.

“People are looking for options when it comes to how they get protein,” says Dan Curtin, president of Greenleaf Foods, the plant-based subsidiary of Maple Leaf Foods. “It’s not that they’re going to stop eating animal meat, but that they want more choice.”

Beyond Meat burger.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

How fast can the fake-meat industry grow? Early reports suggest widespread interest at fast-food chains, especially in Canada. Greenleaf recently struck a deal to offer its Lightlife burger at Kelseys restaurants, while Tim Hortons announced this week that it will be adding a Beyond Meat version of its breakfast sandwich to its menu.

Still, it’s possible the trend will plateau, or even fizzle, once the initial buzz dies down. Many reviewers, at publications ranging from Barron’s to Food & Wine, praise Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods for providing the most convincing fake meats yet, but the consensus is they still fall far short of the savoury experience of real meat. In Barron’s taste test, people had no trouble identifying real meat from the fake alternatives.

Future iterations of meatless meat are likely to further narrow the taste gap, but it’s not clear whether they will prove to be significantly healthier than their real-meat counterparts. As things now stand, many of the faux-beef burgers contain substantial levels of sodium. For weight watchers, there is not much difference between the 270 calories in a Beyond Meat patty and the 290 calories in a similarly sized beef patty with 80 per cent lean meat.

Beef producers are confident their product will retain its appeal. “Consumers love the taste and texture of beef,” says Jill Harvie, manager of public and stakeholder engagement at the Canadian Cattlemen’s Association. Meat is a rich source of vitamins and iron, she says. Furthermore, cattle ranching helps to maintain Canada’s grassland, which recycles greenhouse gases and serves as a habitat for wildlife.

Price is likely to be a key factor in determining how many consumers make the shift to fake meat and how frequently they do so. Many shoppers already regard beef as a luxury product, Dr. Charlebois says, and the thought of paying even more for an artificial version could scare off many people who would otherwise like to eat more plant-based proteins.

The price issue could ease with time, however. As plant-based companies scale up their production, fake meat should become cheaper. “You are always going to have to face the fact that a plant-based product will involve more processing steps,” Dr. Marangoni says. “On the other hand, growing a pea is lot cheaper than growing a cow.”

It’s still not clear, though, when profits will emerge for fake-meat producers. The sheer number of competitors is likely to put pressure on margins.

For all the excitement over Beyond Meat and its plant-based ilk, the biggest challenge may come from rivals working on cell-based meat – the sci-fi frontier of food production. These companies, which include Memphis Meats, Cubiq Foods and Mosa Meat, are attempting to grow real animal cells in labs. Their approach would produce genuine meat, but from vats rather than from animals raised on farms for slaughter. By doing so, the environmental impact of meat production would be slashed.

It’s still anyone’s guess whether this technology will prove to be practical, but it has attracted attention from major backers. U.S. food giant Cargill, meat giant Tyson Foods and drug maker Merck have all invested in cell-based startups. If things go according to plan, the Good Food Institute expects cell-based meat to start hitting the market in 2021.

If nothing else, the clash of rival approaches and companies suggests fake meat, broadly defined, is going to be a growing presence on grocery shelves. “An influx of new products is coming,” Dr. Charlebois says. “What people should remember is that this is a very immature market. The products we’re seeing now are just the beginning.”

Yves burger.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

A nutritional comparison, meatless vs. meat:

Beyond Burger

For each 113-gram burger:

Calories: 270

Cholesterol: Zero

Sodium: 390 milligrams

Protein: 20 g

Real beef burger (Irresistibles Naturalia brand from Metro)

For each 128 g burger:

Calories: 310

Cholesterol: 70 mg

Sodium: 320 mg

Protein: 19 g

Ian McGugan

Ian McGugan