Many investors seem worried about the devastating consequences of a global trade war. But before surrendering to pessimism and selling everything in your portfolio, you may want to consider the surprisingly matter-of-fact conclusions from economists who have pondered such a potential conflict.

If nothing else, the forecasters can help quell fears that we’re teetering on the brink of another Great Depression. Many people have drawn comparisons between the current surge in protectionism and the similar wave of nationalism in the 1930s. However, even an all-out trade war would probably result in a downturn more like the 1973 oil crisis or the early 1980s recession than the Dirty Thirties or the financial crisis, according to a Capital Economics report published on Monday.

Granted, the pain from a trade war would be felt unequally. Among the hardest hit victims would be Ontario factory workers. They have already endured a miserable decade and, in a worst case, they could be smacked yet again by the imposition of tariffs on Canadian-made cars. But even accounting for that pain, the overall impact of auto tariffs on the Canadian economy would be modest, according to a recent Toronto-Dominion Bank analysis.

The key message here is that investors should not do anything rash. Trying to dip in and out of markets to stay one step ahead of possible trade clashes is a mug’s game. To see why, consider some key numbers:

25 per cent: It’s important to put the current risks in perspective. Royal Bank of Canada economists place a 25-per-cent probability on an outright termination of the North American free-trade agreement. They see another 15-per-cent chance of an outcome in which the United States wins in some decisive way.

However, the RBC analysts still tilt toward optimism. They believe there is a 60-per-cent chance of an outcome in which Canada, the United States and Mexico compromise on a mutually agreeable new deal or the existing NAFTA agreement simply gets renewed with no significant changes.

The market seems to be even more optimistic. The S&P/TSX Composite Index is trading at nearly exactly the same level at which it began the year. It doesn’t appear ruffled by all the fire and fury over the NAFTA talks.

Whether you prefer the RBC probabilities or the even deeper state of calm implied by the market, the conclusion is that we’re still a long way from an emergency scenario.

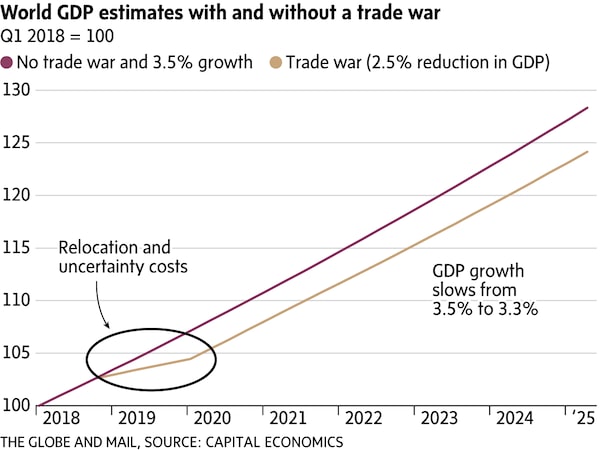

2 per cent to 3 per cent: But what happens if the worst case comes to pass, NAFTA gets shredded and the world collapses into an all-out trade war where every government around the world imposes blanket tariffs of 25 per cent on all imports? In that ugly scenario, world output would fall 2 per cent to 3 per cent, according to Capital Economics.

Such a decline would be painful, but it would be more like the early 1980s recession than the Great Depression. “Once the world has adjusted to the higher tariff levels, it should return to a trend growth rate,” Capital Economics says.

To be sure, there would be some inevitable losses in efficiency because of tariff barriers, which could drag the trend growth rate down to 3.3 per cent a year instead of 3.5 per cent. But the overall impact would be limited. By 2025, world GDP in the trade-war scenario would be around 3 per cent shy of where it would stand in a world that sidesteps conflict, Capital Economics says. This loss of potential output would be sad and frustrating, but hardly catastrophic.

No. 1: Of course, a global trade war wouldn’t hit everyone the same. By Capital Economics’ math, Canada is the No. 1 potential casualty simply because so many of our exports are tied to the U.S. market.

So how big a hit would Canada suffer? In an analysis published last month, Brian DePratto of the Toronto-Dominion Bank considered possible outcomes in the unlikely event that the United States decided to go full protectionist and levy tariffs of 10 per cent on auto parts and 25 per cent on vehicles. In that case, Canada would suffer a modest pullback, in which economic growth in 2019 would fall by half a percentage point and the economy would stagnate for two quarters, he estimated.

Mind you, the national figures hide the extent of the pain that Ontario would feel. One in five factory workers in the province could lose their jobs. “Such a shock would be enough to erase all of the gains (across all industries) in employment that Ontario experienced over the past two years,” Mr. DePratto writes. On top of that, the loonie could depreciate by 8 per cent to 15 per cent, raising the price of imports for all Canadians. And spillover effects from layoffs could hit housing markets and retail sales, particularly in the Golden Horseshoe area, where much of the country’s auto industry is clustered.

Still, the country would not be devastated. If Washington imposed auto tariffs, Canada’s gross domestic product would likely shrink 1.3 per cent and unemployment would rise 0.8 percentage points, but most of the lost ground would be made up within two years, leaving the level of output only 0.2 percentage points below the business-as-usual scenario, TD estimates.

10 per cent: Investors should remember that the Canadian stock market is not the same as the Canadian economy. While the auto sector could be hit hard by potential tariffs, the big automakers aren’t listed on the Toronto exchange. In fact, industrial stocks make up only 10 per cent of the S&P/TSX Composite. They’re far less significant than the financial and energy sectors.

This isn’t to say that the market would simply ignore a trade war – no doubt banks and oil companies would also feel the effects. But it’s likely that conflict would not be as catastrophic as many investors think. And, of course, the balance of probabilities still argues we won’t have a trade war at all.

So take a deep breath and calm down. At least for now, this is not a time for panic.

Ian McGugan

Ian McGugan