In the 1966 documentary Ladies and Gentlemen, Leonard Cohen, the prodigal poet, returns to perform for a hometown audience in Montreal. As he leads the filmmakers around his local haunts, Cohen appears to be wearing the Famous Blue Raincoat he later immortalized in verse. "I had a blue raincoat. It was a Burberry," Cohen told an interviewer of the garment. "And it had lots of buckles and various fixtures on it. It was a very impressive raincoat. I'd never seen one like it. And it always resided in my memory as some glamorous possibility that I never quite realized." The artist, who could articulate the depths of the human heart with unmatched precision, also, it seems, had an intuitive understanding of the relationship between clothing and identity.

A year after his death at the age of 82 in November 2016, the city of Montreal is preparing to host a series of large-scale events dedicated to that persona, including a multi-disciplinary exhibition at the Musée d'art contemporain that invites more than 40 contemporary artists to interpret Cohen's work. Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything, opening Nov. 9, will include virtual reality, music, interactive installations and photography. Yet Cohen's relationship to fashion goes unexplored, despite the fact that it's a frequent motif in the poems, novels and music that have inspired so many.

Consider how many Leonard Cohen profiles over the years have spent paragraphs describing his soigné wardrobe. For a 1988 article, one Rolling Stone journalist observed that Cohen's chalk-striped, double-breasted sartorial splendor remained intact despite a July heat wave, in part because Cohen slipped off his trousers partway through the interview and carefully draped them over a chair to prevent them from wrinkling.

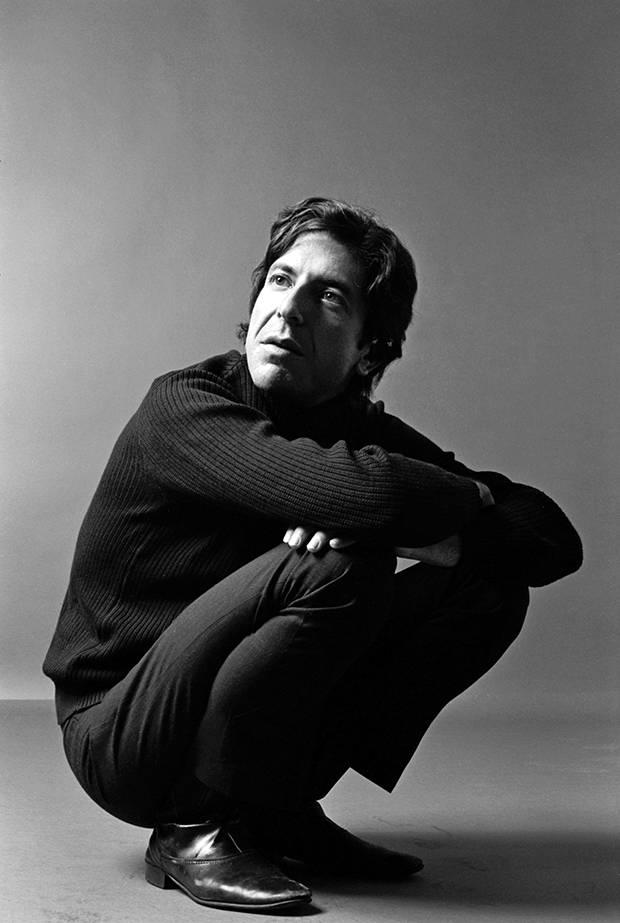

Photographed in Amsterdam in 1972, Leonard Cohen sported a more bohemian look than the melancholy style that became his signature.

GIJSBERT HANEKROOT/REDFERNS/GETTY IMAGES

"When you take a look today, his style is very reminiscent of Margiela meets Dries Van Noten," says Olie Arnold, style director for Mr. Porter, who also notes that the godfather of gloom's sombre outfits mirror the themes of Cohen's songwriting and poetry. "There was this sartorial elegance to him, and it always felt effortless and thrown together. He was proper cool, rocking a trilby with beads on his wrist." Today, a music industry marketing executive would call that synergistic style "on brand," but Cohen came about his interest in fashion much more authentically.

To a man raised in a well-to-do Jewish family dedicated to the garment business, style mattered from an early age. Cohen's grandfather, Lyon, took over Montreal's Freedman Company, which made suits and coats for retailers across Canada, in 1906. Biographer Ira Nadel writes that the Cohen household, "reflected his father's formality rather than his mother's earthy personality." Nathan Cohen, Nadel says, always dressed in a suit, and his son was expected to wear one to dinner (in his book Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, Harvey Kubernik suggests Nathan ruled with such formalism and propriety that he even wore vested three-piece suits and spats on family vacations to Florida).

In the late 1950s, after a stint at Columbia University in New York, Cohen returned to his hometown and worked at the family firm. In his own work as an aspiring writer though, suits figured as symbols of conformity. His look at the time was that of the rebel intellectual by way of Greenwich Village. "Hanging out with Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, you can see how his style was of the moment," Arnold points out. "I think things like caps and rollnecks worn by the Beat generation set the tone for his style."

"I can't find any clothes that represent me. And clothes are magical, a magical procedure," Cohen told interviewer Michael Harris in 1969. "They really change the way you are in a day… until I can discover in some clearer way what I am to myself, I'll just keep on wearing my old clothes."

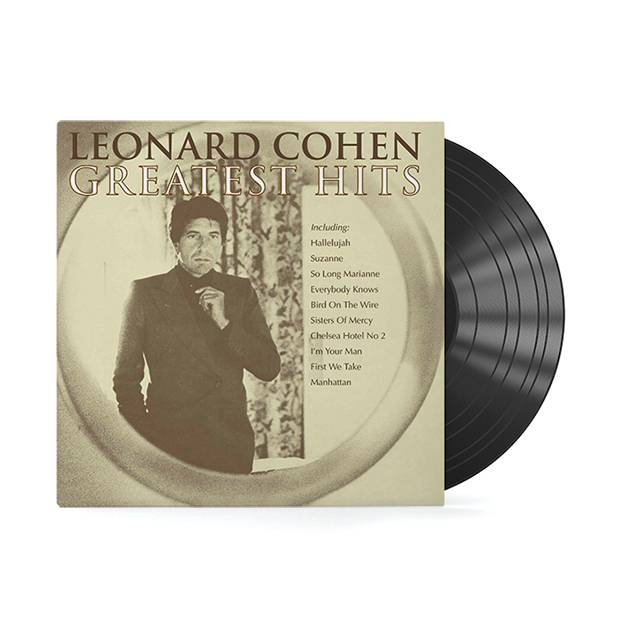

The more sober uniform that became his signature begins to emerge in 1975, on the cover of the Leonard Cohen Greatest Hits album: a sepia photo captures his suited reflection in a Milan hotel room mirror as he's adjusting his tie. By the time of The Future, Cohen's first real commercial success in 1992, he had mastered this wardrobe persona. Dark, double-breasted pinstripes with wide peak lapels (usually Armani), a bolo or tightly knotted necktie and, occasionally, a tie bar. Ordained a Buddhist monk in 1996, Cohen sometimes wore Armani suits while he meditated, and imbued his everyday look with such monastic intention the blazers and trousers may as well have been liturgical vestments.

It's that sullen wardrobe aesthetic that most often makes its way onto designer mood boards, but it is, in fact, Cohen's music and lyrics that have the biggest impact on fashion collections. The strains of Last Year's Man accompanied deconstructed Margiela men's wear during the Spring 2017 shows, for example. As it happens, Giorgio Armani has said his favourite song is Suzanne.

Over the years, lyric fragments have worked their way onto the runway. In the spring of 2009, Raf Simons offered a stark black beach towel bearing the oft-quoted Anthem verse: "There is a crack in everything/that's how the light gets in." The knits of Eckhaus Latta's Fall 2017 collection are emblazoned with the lyrics of Cohen's 1974 song Is This What You Wanted. And New York designer Thaddeus O'Neil found inspiration for his Spring 2018 men's-wear line in the pages of Beautiful Losers, Cohen's mystical and psychosexual novel from 1966. Lest you think Cohen would grimace at all these sartorial homages, shortly after his world tour ended in 2011, he collaborated with Comme des Garçons on a capsule T-shirt collection featuring his words and drawings.

Cohen also enjoyed at long friendship with former Vogue Paris editor Joan Juliet Buck and, in the 1980s, dated fashion photographer Dominique Issermann, who directed the videos for Dance Me to the End of Love and First We Take Manhattan. The latter's black-and-white montage of meaningful glances and abandoned suitcases resembles an early Calvin Klein perfume commercial. Despite the lyric, "I don't like your fashion business mister," its stark style – and the noir anti-hero figure of Cohen wandering a windswept beach in a dark overcoat – reverberates through the industry to this day.

Visit tgam.ca/newsletters to sign up for the Globe Style e-newsletter, your weekly digital guide to the players and trends influencing fashion, design and entertaining, plus shopping tips and inspiration for living well. And follow Globe Style on Instagram @globestyle.