In her multimedia installation, Piece Work, Canadian artist Sara Angelucci turned men's suiting inside out, literally and figuratively. The under-the-radar Art Gallery of Hamilton exhibition, which ran until mid-May, included sonic elements, moving images and still photography that revisited her late mother Nina's personal history in the city's garment trade. It also highlighted her mother's employer, Coppley Apparel Group, where she began her career in 1957 in the "fancy pants" department. Today, Coppley is one of just a few remaining manufacturers of tailored men's clothing in Canada. With a workforce of 250 employees from 36 different countries, it continues to be as influential on the vitality of downtown Hamilton as it has been on the history of Canadian men's wear.

It was at the turn of the last century that Hamilton earned its Steeltown nickname. The city's foundries originally flourished in its North End following the arrival of the railroad in 1854 and made everything from stoves and office fixtures to boilers and cash registers. But the shine of steel often obscures the city's important early life as a manufacturer of textiles and garments – once major contributors to its industrial economy. Admittedly, Needletown doesn't have quite the same ring to it, but yarn, textile and knitting mills and garment factories like Coppley contributed as much as metal to the fabric of the city.

Today, Coppley is the oldest surviving garment manufacturer in Hamilton, where relative newcomers include specialty purveyors such as Niko Apparel Systems and Bombardieri uniforms. Coppley can trace its lineage all the way back to 1883, when it was known as John Calder & Company. (Its sandstone renaissance revival-style headquarters and factory at the corner of York Blvd. and MacNab St. North, designed by architect Frederick Rastrick, dates back even further, to 1856.) When Calder died in 1900, three former employees took the business over and renamed it Coppley Noyes & Randall Ltd.

"From 1900 through to about 1952, men's wear in Canada was driven by the war years, drifting back and forth from civilian to military wear," explains Warwick Jones, the executive chairman and unofficial Coppley historian who has been with the firm for 48 years. When Max Enkin bought the company in 1950, production was down and there were fewer than 60 employees, so he decided to focus on fashionable civilian wear and, with sales manager George Ryan, began criss-crossing Canada on sales calls.

Executive chairman Warwick Jones.

RODRIGO DAGUERRE

Enkin built up Coppley's suit business across the country, Jones says, through generous sales terms to the many emerging independent specialty men's-wear retailers of the era – names like O'Connors, Harry Rosen and Henry Singer.

"If Max liked the look of a business, he went out on a limb and offered him extended credit," Jones recalls. "Our basic business philosophy was always about relationship selling."

The Piece Work show's main series showcased twenty-four pairs of workers' hands, each performing one of the many intricate steps involved in crafting a suit – from tacking and sewing welts, to serge assembly and jump basting. A suit can have as many as 123 parts, Coppley president George Lindsay says, only half joking when he adds that even an introductory tour of the factory takes two hours and is nicknamed Coppley College.

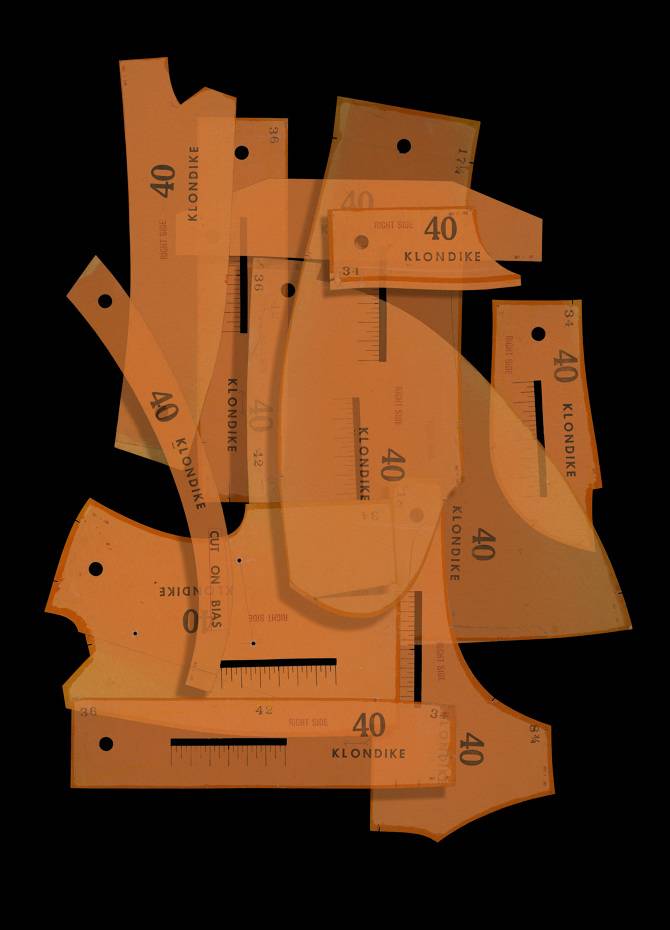

The exhibition also included lightbox images of paper patterns for ubiquitous Coppley styles like the Klondike from 1956 and the wildly popular Dude from 1967. Jones laughs ruefully as he remembers another particularly daring 1970s bell-bottom suit with two-inch cuffs made with a high-end double knit sourced from France; it sold strongly for many years. In the early 1980s, a top seller was cut from shiny Italian mohair and wool fabric meant for evening suits and tuxedos that "made sharkskin from the 1960s look conservative!"

When the company expanded sales to the United States in the 1990s, "one of the reasons we were so successful, is that we were viewed as very European, as compared to what they could buy domestically," Jones says. That's because, even as the company modernized aspects of production with computer-assisted cutting and state-of-the-art efficiencies to become known for its seven-day turnaround, it retained a distinctive old-world touch and a preference for fine imported cloth from Italian mills including Reda and Barbieri.

The sharp, continental-style tailoring responsible for Coppley's success dates back to its earliest "civilian" suits and trousers. The look was the result of a timely confluence of factors. When he purchased the company, Enkin also happened to be a key player in the Tailor Project, a Canadian postwar community integration plan that resettled more than 2,200 skilled tailors from the displaced persons camps of Europe (this refugee humanitarian work continued through subsequent waves of immigration and Enkin received both an OBE and the Order of Canada for his efforts), while alleviating Canada's skilled-labour shortages. Along with the influx of immigrant workers like the ones featured by Angelucci, ten such old-world-trained tailors were placed at Coppley.

These men, and their subsequent apprentices, set the tone for decades. One of the early arrivals, Danny Mascio, took a young errand runner named Santo Gallo and trained him to be his talented understudy. Gallo worked at Coppley for more than 50 years, spending the last 35 of his career as its chief in-house tailor.

Since 2012, the company has been owned by New York-based IAG and has focused much of its manufacturing capacity and technological innovation on the custom-suit market. "Little did we know how important made-to-measure was going to become," Jones says. The factory crafts a robust average of 1,000 suits a week for dozens of upscale clients such as Rubinstein's, Woodbury and Butch Blum in the United States, and Henry Singer, Dugger's and Harry Rosen in Canada. Coppley also collaborated with Toronto-based Garrison Bespoke on a style called the Blazer Suit that's meant to help a younger customer transition between formal and casual occasions. Needless to say, respecting its history isn't holding Coppley back from charting its future in Hamilton and beyond.

Visit tgam.ca/newsletters to sign up for the Globe Style e-newsletter, your weekly digital guide to the players and trends influencing fashion, design and entertaining, plus shopping tips and inspiration for living well. And follow Globe Style on Instagram @globestyle.