When it was announced last summer that Toronto Fashion Week, backed by international events company IMG, was dead in the water, the news was met with both disappointment and relief. Though it was the end, the news signalled the potential for a new beginning – or four. In 2017, Re\Set Fashion (featured on Pages 6-7), FashionCan, Toronto Women's Fashion Week and Toronto Fashion Week (under the ownership of Freed Developments) will all compete for the attention of a relatively small audience. Ask industry insiders if that makes any sense, and the most candid answer you'll receive is a hesitant shrug, though not from Susan Langdon, the executive director of the Toronto Fashion Incubator (TFI). "It's great to see the community and industry wanting to do something," says Langdon. "I think if there's enthusiasm, why curb it?"

A consummate optimist is just what the city's fashion community needs, and Langdon has been one since the beginning of her tenure at TFI in 1994. It has become a tradition for the incubator to shine a light on the next generation of hopeful Canadian talent with its annual New Labels competition, a designer showdown and runway presentation that, this year, will kick off Toronto Women's Fashion Week during the TFI's 30th anniversary gala on March 9. Over the past three decades, the TFI has played an important role in boosting emerging names – notable alumni include the labels Smythe, Greta Constantine, David Dixon and Line Knitwear, the UK-based designer Todd Lynn, and Pina Ferlisi, a former designer for Marc Jacobs and McQ turned creative director for Henri Bendel. But with government funding for the fashion industry scarce, can the TFI take Canadian fashion to the next level?

When the TFI was born in 1987, Langdon had a burgeoning design career of her own. "I worked my way up to securing a financial backer – two, actually," she says. "When the recession hit in '93 – the really bad one – I was developing an evening-wear line. People stop buying evening wear in a recession." After her backers pulled out and she couldn't afford to buy the company, Langdon was offered three opportunities: a full-time tenured position at Ryerson University's School of Fashion, a grant to launch a new label or the chance to helm the Toronto Fashion Incubator.

Executive director Susan Langdon has been with the organization since 1994.

Shalan&Paul

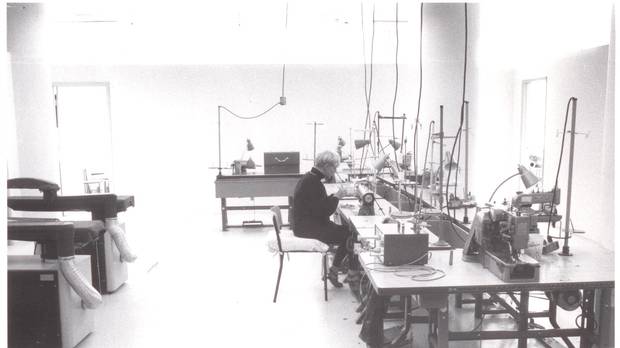

The TFI was originally launched by the City of Toronto as a centre to help new fashion designers create and maintain successful businesses. At the time, the fashion industry was one of the largest employers in Toronto, responsible for 20,000 jobs. As production began to move offshore, TFI's mandate to keep creatives creating by providing business knowledge became even more important to the local economy and spawned international copycats in cities such as New York, Chicago and Sydney. Today, TFI maintains its original format, only on a larger scale. Its headquarters, a heritage building on the Exhibition grounds, is home to 10 low-cost studios, communal production and social spaces and Langdon's office, where designers huddle for mentorship meetings about everything from balancing budgets to import and export strategies.

The communal aspect of TFI is one of its biggest strengths according to current resident Sid Neigum, who says he's bolstered by the creative energy in the space. "It's just like having roommates," he says. On a more practical note, the fledgling designer, who shows his collections in London, can keep overhead costs low while growing his business. Each resident has 24/7 access to the studio, its machines and its resource centre, which includes the use of pricey trend-forecasting services such as the Worth Global Style Network and Peclers Paris. New to the space is Spencer Badu who just relocated from Calgary to build his line, S.P. Badu. "I think the mentorship and the environment is the biggest [help]. I have [access to] people that were in my shoes before that can give me advice," he says. "Plus, having a studio and all the machinery at my disposal is amazing." TFI also operates an 800-member strong outreach program for designers working independently.

TFI has received municipal funding for the last three decades. In 1987, the city grant covered 83 per cent of its operating costs. Today, only 28 per cent is covered by city funding. "Everybody understood that this business model was never meant to be self-sustainable," says Langdon. Since 1994, TFI's membership fees have stayed relatively flat (in 1988, a studio cost $400 per month; today it costs $575) and the non-profit has always targeted new graduates, newcomers to Canada and small businesses.

At times, TFI also received federal and provincial funding, though Langdon declines to confirm the exact amounts or percentages. In recent years, securing higher-level funding has been challenging. "If you compare us to other consumer products or services, such as television and film, these are highly commodifiable products that are transportable and rooted in intellectual property law, yet they have access to funding," says Ashlee Froese, a partner at the law firm Fogler, Rubinoff LLP and a branding and fashion lawyer who acts as a mentor at TFI. In 2015, Froese unsuccessfully petitioned the Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport for a piece of its $800-million investment in cultural industries that year. Her proposal was to create an agency similar to the British Fashion Council (BFC) that would be dedicated to delegating fashion industry funds, some of which (it was hoped) would go to the TFI. "The fact that TFI has been around for three decades shows that people need it and that it has a position in the industry," she says. "As with many incubators, increased funding impacts overall effectiveness."

TFI resident Sig Neigum.

Mark Binks

The BFC is largely held up as the gold standard in the industry. A fully synchronized system, complete with municipal and federal funding and strong retailer support from the likes of online giant Net-a-Porter, has allowed young London talent to become some of the biggest industry names. "When I went to London last February to see Sid's first show, I met with the British Fashion Council," says Langdon.

"I asked them, 'How does this model work?… Where does this money come from? It comes down to the government and all the constituents understanding and accepting that fashion is a viable industry that needs to be recognized as a huge economic driver. We don't have that recognition in Canada." Currently, the provincial and federal grants that TFI receives focus on youth initiatives.

"Ultimately what we're looking to support is the creation of jobs and businesses in that sector," says Chris Rickett, the manager of entrepreneurship services at the City of Toronto. Rickett, who works on the City's Business Incubation Program, which also covers the food and business sectors, says the city is committed to fashion. "As long as our budget gets approved, our goal is to continue to be involved with the Fashion Incubator."

The city's data shows the fashion industry still generates $1.4-billion every year and TFI claims to have created 18,000 jobs over its lifetime. For its residents to keep their spots recognition from the industry and media, as well as growth potential, are taken into account, but certain financial expectations must also be met, including achieving approximately $100,000 in sales after about five years in business. "We're a very sector-specific incubator. We haven't adopted this thing called mandate creep," says Langdon, referring to the strategy of expanding the scope of an organization to generate additional revenue. "Our board has been very true to what our goal was and that's to service fashion entrepreneurs, especially in the startup stages. As tempting as it may be to chase after this group and that group, we would lose our focus."

While success in fashion in Canada is often measured by fame, Langdon's view is more pragmatic: "If you can survive five to eight years in this business, run a viable business, continue to make an innovative product that people want and desire and you've started to carve out a brand name for yourself… that, to me, is success."