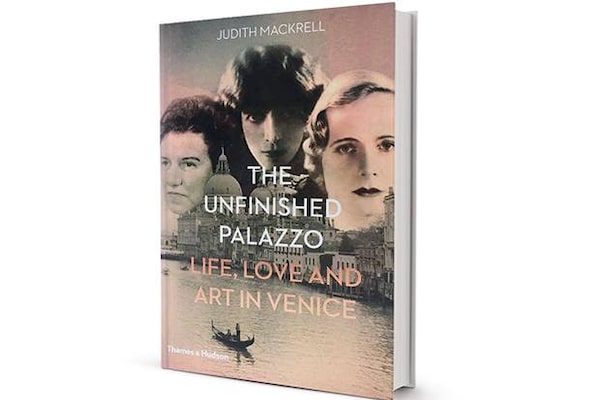

The palazzo dei Leioni, the party palace on the banks of Venice’s Grand Canal that remained unfinished because its original builders ran out of cash after the first storey, is the subject of Judith Mackrell’s book The Unfinished Palazzo.

On the cover of Domino's autumn quarterly, Maggie Gyllenhaal perches on an opulent floral settee. Inside the magazine, we learn that it isn't her home being featured but Café Sabarsky at New York's Neue Galerie, where the banquettes are covered in Otto Wanger's 1912 floral. It's an interesting cover concept since we often enjoy the voyeuristic aspect of shelter magazines because of the connection they make between who had a hand in creating a space and how it looks. Appreciating the design of a house is inevitably a way of getting to know the women who live there. Exploring the stories of their chatelaines through the rooms they inhabit, decor allows us to examine an individual's attitude towards living. As Gloria Vanderbilt liked to say, "Decorating is autobiography."

I thought about this while touring the Sotheby's sale of Bunny Mellon's "Jewels and Objects of Vertu" estate sale a few years ago – how her vast possessions were not merely on shelves but staged throughout the building. The auction house re-created entire rooms from several of her residences, including the use of whimsical vegetable-shaped ceramics from her Virginia farm.

The palazzo dei Leioni, the party palace on the banks of Venice's Grand Canal that remained unfinished because its original builders ran out of cash after the first storey, is the subject of Judith Mackrell's book The Unfinished Palazzo. The single-storey 18th-century villa is now the Guggenheim Collection museum, and in her book, Mackrell goes in search of its inhabitants, Luisa the Marchesa Casati, Doris Castlerosse and Peggy Guggenheim, three unusual and colourful women, each eccentric in her own way and each inhabiting the house with the hope of redifininign her identity.

The flamboyant Casati was already ahead of her time aesthetically in 1908, decorating her flat in Rome in the stark black and white scheme that only became fashionable in the mainstream after the First World War. In Venice, the self-invention and artifice of her daily life as a woman who once hiked the Grand Canyon in leopard-skin trousers and a lace veil resulted in an all-gold main salon, with gilded lace curtains, gold-plated staircases and many mirrors to reflect herself (plus a menagerie of exotic animals in gilded cages for amusement). Next, Castlerosse (the great-aunt of model-actress Cara Delevingne) used the palazzo to relaunch her social career and assert social standing in the mid 1930s. She remodelled it into a summer salon, with mosaic floors inlaid so that the glinting sheen of mother-of-pearl would suggest opulence underfoot. When she purchased the building in 1949, Guggenheim used it to solidify her influence on the modern art world by exhibiting the collection of surrealist, cubist and abstract expressionist works she collected during during the Second World War.

Mary Lovell looks at similar terrain in The Riviera Set, about the 1930s Modernist villa near Cannes formerly known as le Château de l'Horizon. On the rocky shoreline, with a swimming pool chute that went directly to the sea, it was designed by Barry Dierks for retired American stage actress Maxine Elliott and later owned by Aly Khan, who vacationed with wife Rita Hayworth (for their wedding, he purportedly filled the pool with cologne). Elliott, who dressed in white and allowed her hair to go grey to match her surroundings, was a consummate hostess to Edward VIII, Noël Coward and Winston Churchill, when the Mediterranean coast was not quite the playground of the Euro-jet set that it is today. Elliott favoured luxurious pampering – each room was designed with its own terrace. She entertained 30 or 40 at lunch every day and insisted on full evening dress for dinner every night. When cloudy nights obscured the moon, a custom-designed electric false moon hung above the dining table to simulate the magical illumination.

The style world continues to discover such unique spaces. A few years ago, Chanel purchased Gabrielle Chanel's 1929 villa La Pausa, the only one of her several homes designed and decorated to her specifications. After careful restoration, the estate was unveiled again this summer and is now part of the company's heritage identity – "to radiate the culture and values of Chanel," as a statement from the Wertheimer brothers, Chanel's owners, puts it. The all-cream interiors – even the piano was beige! – serve as an extension of Chanel the woman's taste for Art Deco purity. Knowing that the inspiration for the austere design came not from an expectedly grand source but the 12th-century Aubazine abbey orphanage where she spent some of her childhood adds layers to its meaning.

Chanel's powerful personality traded in deceptive simplicity – even in decor. As understated as it may have seemed, Lovell reports that much of the La Paula building's 6-million franc price tag was spent on the expansive slabs of Carrara marble used to construct the villa itself.

Visit tgam.ca/newsletters to sign up for the Globe Style e-newsletter, your weekly digital guide to the players and trends influencing fashion, design and entertaining, plus shopping tips and inspiration for living well. And follow Globe Style on Instagram @globestyle.

Nathalie Atkinson

Nathalie Atkinson