Wenting Li

First Person is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

My family and I will be celebrating Canada’s 151st birthday in Sackville, N.B. Every year, there is a lively community party in the park near the bandstand. There are games, balloons, musicians, speeches, the flag is raised and everyone sings O Canada.

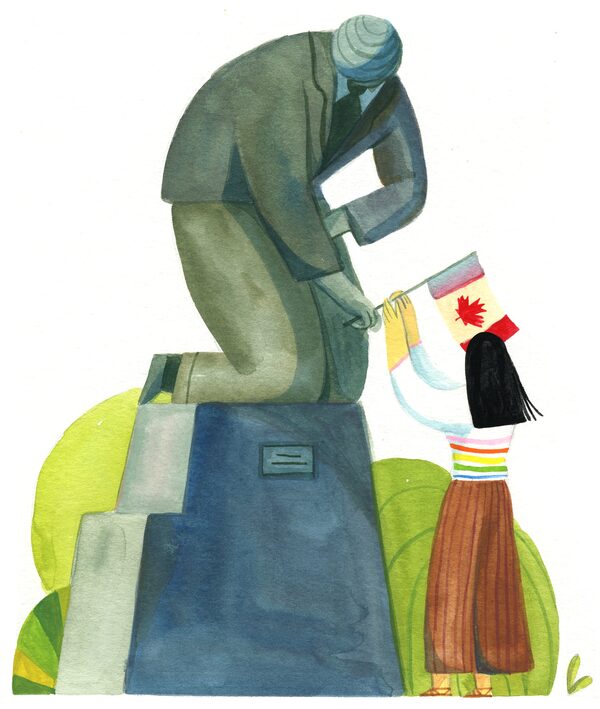

This year’s party will have a special feature. The town will dedicate a bronze statue by Christian Toth to honour Dr. George Stanley, the designer of the Canadian flag, who spent much of his life in Sackville and is buried there. The new statue is a Canada 150 legacy project in the town.

For me, it will be a day of nostalgia. I will be reflecting on the big Canada Day celebrations of my past. I was 13 when Canada celebrated the Centennial of Canadian Confederation in 1967.

Even after 50 years, that landmark remains vibrant and jubilant in my mind’s eye – Expo 67, the Centennial Train and Caravan, the omnipresent Centennial logo, the lighting of the Centennial flame on Parliament Hill (which was intended to be temporary but became a beloved permanent fixture), endless maple leaf cakes, Alex Colville’s Centennial coin designs, the Canadian Armed Forces Tattoo 1967, Bobby Gimby’s Canada Centennial song, and on it went throughout that glorious year.

Canada was coming of age and so was I. It was a proud, confident and exuberant era of seemingly limitless possibilities. The economy was booming, modernization was accelerating at a frenzied pace, and higher education was opening up to everyone of ability.

In 2017, for the sesquicentennial, Canada was a very different place – more mature, diverse and sophisticated, but also more discordant. There have been many bumps and hard lessons for Canadians during the past half century. The mood was much less euphoric for this national milestone. We were beginning to confront our historical myths and demons, particularly the long, painful journey of reconciliation between colonial and Indigenous peoples. Liberal democracy was under siege around the world. The future of the human race seemed unnervingly precarious.

Last summer, my family was invited to a 150 Great Canadian Barbecue hosted by a young couple in their early 30s. They are passionate about all things Canadian and spent weeks planning their homage to Canada’s special birthday. He is of Scottish-Acadian-English-Irish descent and grew up in New Brunswick’s Miramichi; she is of Lebanese and Québécois ancestry and was raised in British Columbia.

Provincial and territorial flags lined the driveway. The national and Canada 150 flags festooned the front veranda. Inside, there was an astonishing buffet – a veritable tableau of Canadian history. It quickly became apparent that our hosts could give master classes to Martha Stewart. Every province had two culinary representations – each identified on a card with the relevant provincial flag. The Canadian delicacies included bison burgers, moose sausages, peameal bacon, Montreal smoked meat, poutine, donair shish kebabs, smoked salmon and fiddlehead tarts. A separate dessert table, draped with a Hudson’s Bay point blanket, held such enticements as bread pudding, Nanaimo bars, Timbits, maple leaf shortbreads and a large raspberry mousse, moulded in the shape of Queen Elizabeth’s head.

This panoply of Canuck gastronomy was set among a canoe paddle, a deer antler, a sheaf of wheat, a tree trunk with a spile and sap bucket – along with real snow (kept in a freezer since March!) and hot syrup to make maple taffy, a miniature log cabin, a Mason glass jar with an embossed crown, an antique wooden Canada Dry crate, an inukshuk, a totem pole, braided sweet grass, a lobster trap, a fishing net and glass float, and a slice of a large log that had taken four hours to saw by hand. Adding further ambiance to this quintessentially Canadian occasion were the hosts’ five-year-old son (at one moment a coureur de bois and then an RCMP officer) and two-year-old daughter (intermittently a Disney princess), who sprinted joyfully among the partygoers with their young friends.

For five hours, the guests at the 150 Great Canadian Barbecue mingled happily, taking it all in literally and figuratively. The Canadian music playing in the background was barely audible above the gregarious conversation. There were Canadians from all across the country – an American who had lived in Canada for years and recently become a citizen, a New Zealander who had married a Canadian, two girls adopted from China whose extracurricular activities include Scottish Highland dancing, a daughter of Stanley (the flag designer), a descendant of a fille du roi, a young Syrian refugee who was just finishing observance of Ramadan, and a Lebanese Canadian who became a citizen almost 40 years ago, proudly wearing a gold maple leaf ring to proclaim his allegiance, and is now a respected scholar of Shakespeare and Machiavelli.

Many of these young people – whose world views are reminiscent of their counterparts in the 1960s – are social activists and deeply committed to the values of equity, inclusion, grassroots democracy and living green. They are the face of the new Canada.

I often despair about the toxic world order in which our children are growing up. But in that sublime moment, I knew that Canada’s future was going to be in good hands.

As a handful of us savoured the afterglow of the party, I felt a profound sense of gratitude for having had the great good fortune to spend much of my life in this sane and safe corner of Nova Scotia – in the best country on Earth. I also thought about the hardships endured by my own ancestors who settled in Canada between 1783 and 1850, building a life denied them in their homelands. What would they think of Canada in the 21st century?

I’ll enjoy Canada 151 but I won’t see Canada 200. My 17-year-old daughter – one of those children adopted from China – will. I can only speculate about how Canada will evolve in the next 49 years, and wonder how she will look back in 2067.

John Blackwell lives in Antigonish, N.S.