Estée Preda/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

First Person is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

I’ve studied the X-rays, trying to be objective. They reveal three rods and 30 screws. The screws bite into bone at regular intervals, their threads visible. The rods fence the spinal column, although one rod extends lower and angles away, suggesting a train track veering off course.

A casual viewer might notice the craftsmanship evident in perfectly placed screws or admire the artistry of the body, a visual ostinato played in vertebrae and disc. It’s hard for me to appreciate the precision or the beauty. I see foreign material, the aftermath of invasion. The screws appear to be everyday fasteners used to hang a picture, but they’re inside my teenaged daughter.

In fact, there are 29 screws, but I round up. Maybe I think that stating the exact number makes me sound like a neurotic mother. I’ve struggled to understand the boundaries of my role, in the events and in the telling of the events. The scalpel didn’t pierce my skin. A parent can feel her child’s pain, but only in translation.

“Is scoliosis a condition or a disease?” she asked, when first diagnosed. She was 11. The Scoliosis Research Society calls it a deformity. Deformity is a deformed word, ugly and harsh, like defect. People rarely speak any more of birth defects. We live in an age that values the person over the ailment, at least linguistically, but the shifting ethos hasn’t reached clinicians, who toss deformity and defect into examination rooms with practised ease, appearing not to notice the emotional explosions. I concede that a doctor’s need for accuracy trumps delicate feelings – the angle of the screw must meet specs, after all. I can accept the incoming terminology, some days.

A year before the surgery that implanted titanium in her spine, my daughter underwent a Chiari decompression. That procedure creates space where nature did not provide it. A piece of skull was removed to accommodate her growing brain and ease the pressure of pent-up spinal fluid. My daughter had brain surgery, a reality I tried to forget throughout that first hospital stay.

And then, the scoliosis procedure – posterior spinal fusion. Posterior meaning rear, but I prefer to think of posterity, a loose notion of future generations. Now she carries two scars into her future: one parting her hair at the nape and another running from between her shoulder blades to her tailbone. Marks on her body, a record of trials endured. Not deformities.

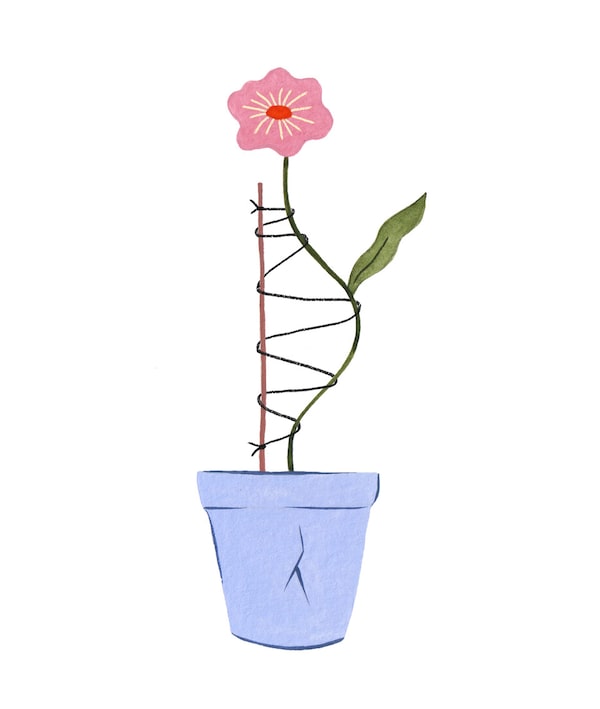

Her first treatment was bracing. A brace is no cure, just an incredibly uncomfortable container designed to keep the curve from getting bigger. Made of thin, hard plastic cast from the patient’s torso, the brace suggests a dressmaker’s dummy with more physics. My daughter’s brace caged her from breastbone to hip, compressing the skin, torquing the spine to counter the force of her own growth, 22 hours a day. That was the ideal regimen, at least. I doubt most patients wear the brace as prescribed, and she was no different. Still, she served hard but spirited time in her brace, choosing a blue camouflage pattern for the device, which she named Alistair. If only Alistair had worked out.

Doctors tracked the progression of her curve at each clinic visit, when she was X-rayed anew. The Cobb angle increased steadily, although experts threw out varying figures. Even on the day of the operation, a doctor told us that the radiologist had measured her curve at 80 degrees, but he believed that it had reached 100.

The number was something my husband and I bandied about during the years of treatment, as if we knew what we were talking about. We had hoped to avoid surgery, but images defied us. There was no denying the curve corrupting the upper thoracic, nor the twisting ribs that jutted on one side. Toward the end of her braced period, anyone who saw our daughter in a bathing suit would gasp. She listed to the left, her waist marked by a fold of skin at the sideways bend.

She had the posterior spinal fusion surgery when she was 14. Early in the morning, we kissed her goodbye after signing off on a list of life-threatening risks. She looked tiny and pale gliding away on the stretcher. I cried when they took her.

My husband and I roamed, unable to settle. In the surgical waiting room, patient surnames flipped across a giant board: In Holding, In OR, In Recovery. People came to the board and stared up as if checking on a delayed flight. We killed time in the cafeteria, sending text-messages to relatives. We slept in our car in the parking garage, which was hot and smelled of exhaust. I slept again later, sprawled on a bench while rush-hour commuters stampeded past. Trapped in the hospital, wrecked and fearful, I didn’t care. Sleep came, full of mercy.

Twelve hours passed before we saw her again – finally In Recovery. Though groggy, she grabbed our hands, me on one side, her father on the other, and managed a wry complaint: “Remind me again why I can’t have any water.”

Our beloved returned to us. She didn’t yet know what we knew about her insides. The head surgeon had approached us for a huddle, as the surgery continued without him.

Leaning against a wall, he called the X-rays to his phone, swiping the screen. First, the before picture: “Note the rigid deformity,” he said. Anyone could see it, but the crisis had been averted. That was his message, the news we longed for. The proof was in the after image: a spine held in check by hardware, corrected by medical science. The surgeon was pleased.

In the corridor we viewed screenshots of our child’s bones while she slept on the operating table and someone closed her up. We marvelled at her new condition, straight as three rods and 30 screws.

Laura Rock Gaughan lives in Lakefield, Ont.