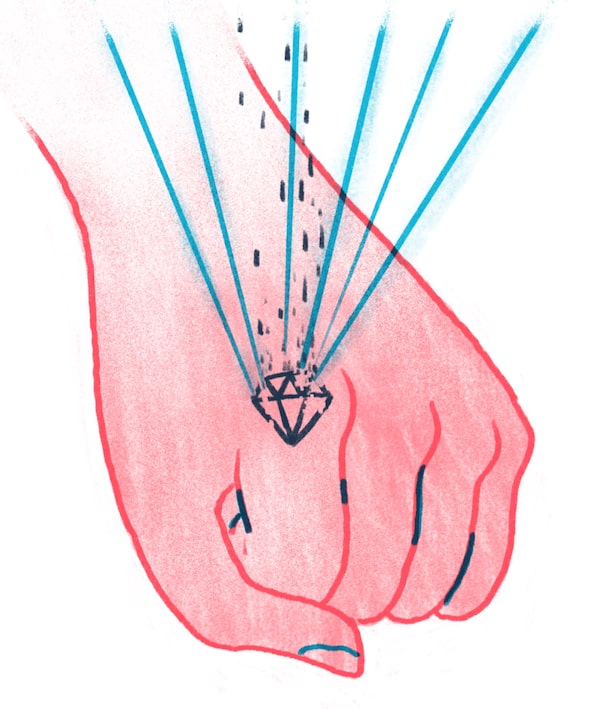

ILLUSTRATION BY DREW SHANNON

First Person is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

I see Kathy once every six weeks for 15-minute sessions. By the time we are done, I will have virgin skin and Kathy will have all my money. Kathy is my laser tattoo removalist.

Her work space is clean and sparse, with various pamphlets tucked neatly into display cases; acne scarring, cellulite – I have all the unsightly things that her clinic promises relief from. Even though her clinic is located in a Northern Ontario strip mall across from a Tim Hortons, I sense that it is still the kind of place that judges you for being poor. One session alone costs as much as a high-end laptop or a week-long, all-inclusive Caribbean vacation.

I am giving this clinic my money and the staff have to be nice to me, I remind myself as I walk in, fully expecting to be scoffed at for wearing thrift-store shoes. Instead, I am greeted by the receptionist’s warm smile and offered a cup of tea to sip while the laser warms up.

I can’t tell you how many tattoos I have. I can only say that I’ve never been able to afford any that were elaborate or skillfully executed. I have willingly offered my skin to tattoo apprentices and first timers, let them poke and prod however clumsily. Roughly half my tattoos are self-administered stick ’n’ pokes: Homemade tattoos done with a sewing needle and India ink. I have laboured over these monstrosities for hours, alone in an unfurnished apartment during a particularly self-destructive phase brought on by a yet undiagnosed episode of bipolar disorder. These will be the first ones to go, I’ve decided. Kathy tells me that homemade ink is easier to remove, requiring fewer sessions, which is heartening.

I pull up my pant leg to reveal what looks like a skateboard stabbing a heart with a gardening tool. An abstract design, with an ex-lover’s name etched on top for good measure. To be clear, this person does not love me. If anything, they probably hate me. We do not talk or have any connection.

“Can you make this go away please?” I ask Kathy. What I am really asking her is to make me a new person; one who has made a different set of choices in life.

What I am really asking her is to help me lie.

This clinic uses a PicoSure laser, which Kathy insists is the world’s best technology for what we are doing. I trust her because her husband is a doctor (she reminds me of this several times during our short session). The machine looks like a futuristic MIG welder and retails for well over $100,000. Unlike other lasers, which use heat to break up the tattoo, this one sends short, intense bursts of energy that shatter the ink. It hurts like hell, but the pain is worth it. Seeing the fresh bits of skin gives me the same luxurious feeling I get while driving my parents car in the suburbs, pretending to be middle class.

Kathy doesn’t ask me any uncomfortable questions about the tattoos’ origins (“I was a dumb teenager!” is a lie I volunteer unprompted) or their meaning (they are meaningless), she simply wields the laser as it creates white froth over the colourful lines. My skin blisters. The blisters harden to scabs. Days later, the scabs come off with flakes of colour inside.

I got my first tattoo at 21 in the throngs of euphoria – a diamond on my left finger to commemorate the brilliant shine of limitless youth. At the time, it was a self-imposed barrier to any prospect of corporate employment. Ten years later, it just looks sad and withered as my hands begin to show signs of aging. Unfortunately, I didn’t stop at just the one. More ink appeared on me with every manic episode. By the time I was 30, my arms were covered in permanent crass doodles. I made them look childish on purpose. They were supposed to represent innocence, or something. Now, there is nothing I would like more than to make them disappear. No more wincing through yoga class. No more long sleeves in summertime.

It’s not like my tattoos make me a social pariah, per se. Tattoos are everywhere these days, not just decorating the forearms and sternums of your local barista, but peeking through the uniforms of police officers and firefighters. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has a tattoo, so does my dentist.

Luckily, my current bosses couldn’t care less about my ink. I work in an automotive plant where a large part of the work force consists of the unfortunately tattooed, as well as guys missing chunks of their ears, for fashion. But, say one day I want to do something more meaningful than push buttons on heavy machinery. Say I want to work in a nice hotel someday, I just can’t do that with finger-knuckle tattoos. It sends the wrong message and they always makes me feel self-conscious, if not slightly criminal.

After a couple of treatments, my finger lettering looks like a sign that’s been chipped off, but not yet painted over. Kathy says fingers are the most painful because the skin sits right on top of the bone without any protective flesh to absorb the shock of the laser. My skin is pulsing and hot to the touch. Kathy applies petroleum jelly and bandages me up.

It will take many more sessions to remove the tattoos entirely. But I am on my way – I can’t rewrite the past, but I can make a few aesthetic edits as I look toward a brighter future.

Vera Oleynikova lives in Barrie, Ont.