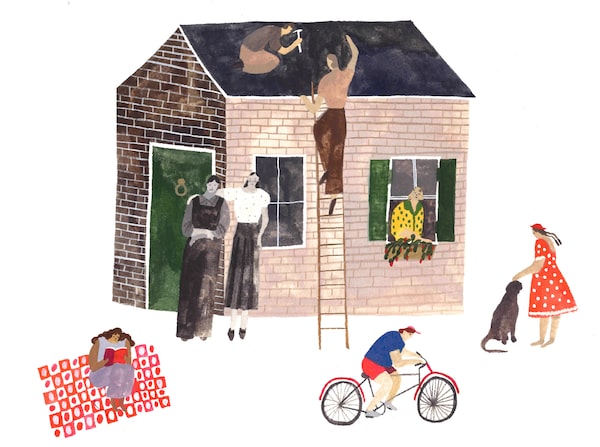

Illustration by Mary Kirkpatrick

First Person is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

We made the trek to visit the family homestead this summer, something we rarely do these days. The land has passed on to other owners and the trip is mentally and physically exhausting. Going to visit our childhood home is anything but child’s play. We heard through the grapevine that a tornado-force wind had damaged the buildings. I flew into Saskatchewan and my mother and I set out on a two-hour drive through the province’s back roads to investigate. We fully expected to see nothing more of our 100-year-old ancestral home than a big pile of rubble. After all, the house had been abandoned for many, many years.

My grandfather and great-grandfather built the house. They came to the newly cast province of Saskatchewan to farm. Everything around the homestead was cleared by my grandparents. They put in years of back-breaking labour that I can only imagine. Somehow, they cleared hectares of land and planted the first crops grown in Western Canada. While they did this, they lived in a sod hut and then a log cabin. We have a black-and-white photo of the family, my great-grandfather and his wife, standing in front of the sod structure, with their children. They look very grim. I don’t blame them.

Somehow, they drew enough livelihood from the soil to build the homestead: a four-square, clay brick house, designed to be economical yet impressive. It could be judged as stately even by today’s standards. The 1½-storey building was erected with a wide-columned veranda, three dormers set into a large pyramidal roof and large casement windows. The upper panes of the windows contained stained glass imprinted with bright green, gold and red tulips. I loved these windows – they always made us think of summer flowers even in the worst of winter. And Saskatchewan winters are the worst.

We believe the bricks for the house came from the Marion Street Brickyards in St. Boniface, Man. The company sent bricks to Saskatchewan by train, and dropped them off in small towns for the hundreds of Prairie pioneers who were constructing new lives after leaving Europe. My grandfather’s heavy horses likely hauled the tons of bricks needed for our homestead early in spring. The workers laid down more than a thousand bricks, each weighing about two kilograms. I know this because I weighed one that came loose. These bricks stood as a fortress against the elements and as a cathedral nurturing those inside. My father was born in the house, my grandfather died in the house, and I grew up in it. It had been 50 years since I lived in this house but driving on this pilgrimage, it strangely felt like I was going home.

Sometimes we need to freeze a moment to absorb the weight of time. The previous visit was almost a decade ago. The house had always stood out, seen from a distance because of its bright red and beige bricks. But time was taking its toll. The house competed for space with scrappy poplars and tall grass. The veranda’s wooden spindles and upper pillars were rotting. The roof’s shingles bulged and the front and back doors sat unhinged.

It was disturbing. It didn’t look like it did in my mind. I noted a row of blooming lilacs and a wattle garden fence intricately woven by a master, as well as my grandfather’s log plaster granaries built by hand, reminiscent of a French painting. As we walked around the yard, our family did our best to remember what we could about this homestead, to bear witness to those distant lives that followed a daily rhythm here. We’ve already put aside our great-grandfather’s cherished smoking pipe and his horse-hair blanket. But we have to release the house to the past. The day will come soon, I’m afraid, when the house will fall to a pile of rubble. And we know, too, that there will be a day in the future when no one will remember who first farmed this ground.

I don’t need those DNA tests that folks order as kits to find their heritage. I don’t need to search old photos to find my lost family members. I’ve always had it right here in this house, the origins of our family bonds.

It is the same for the 1,000 others in our extended family, descendants of my great-grandfather and grandfather. We live because of the century-old decision they took to stand on this ground and build. We each now have our own timelines and histories to recount. We are electricians and clerks, teachers and athletes and many, many other seekers of adventure. It would give these pioneers much joy, I think, if they could now see the lives spun out from their beginnings. They allowed us to take root. Perhaps we are now the bricks in this house.

On our most recent visit, as we crested the last hill, stones spit off to the side of the car. We should be able to see something or nothing of our homestead in a split second. The Western countryside is littered with buildings like our own. Every year fewer of them remain standing. But sometimes on the Prairies, winds blow in the right direction. A high wind had cut through the yard – it ripped a modern, large steel bin from its concrete foundation and hurled it into a corner like tinfoil. But the wind died out a few hundred metres from the house. Maybe next year the clouds would pick a different trajectory. But for now, 100 years on, the Prairie brick house is solid.

Laura Herperger lives in Calgary.