Mary Kirkpatrick

First Person is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

The way I like to phrase it is that my son dances just above and just below the somewhat subjective line that separates those who are neurotypical and those who are on the spectrum. He “passes for normal” to the untrained eye.

Charlie is 6 and we live with him in the messy and challenging world of autism spectrum disorder.

Right now that mess is literal. We can’t keep up with his collections (currently Pokémon cards) and his compulsive need to create harmonious groupings and random piles of all his things around the house. An autism blogger I follow calls it hoarding, but maybe it’s just messiness. I’m just glad that Charlie stopped putting anything with eyes – stuffed animals, Disney figurines, Lego men – face down on the floor.

More from First Person: Playing hockey outdoors taught me about more than how to score

Looking back, there were hints of the diagnosis to come, but not the ones you might imagine. Charlie made eye contact. He loved being held. He didn’t line up toys, arrange crayons in the perfect order of the rainbow or spin in circles. But parties freaked him out. Even when I whisked him away to a quiet room he’d hyperventilate from crying. For six shattering weeks when he started daycare, he was inconsolable and refused to eat their food. I got special permission to send jarred baby food and almost quit my job until he did a 360 and started going happily, even if he never did greet the other daycare kids in the morning and was usually playing alone when I picked him up.

Charlie had autism all along, but for us the journey abruptly began when he was 18 months old.

He didn’t sail through his “well baby” checkup like his sisters did. He couldn’t say 20 words (not even one, actually), stack blocks or push or pull toys while walking. I wasn’t fussed – boys are slow, they catch up – but our normally calm and collaborative family doctor ordered us to put him on the lengthy waiting list for the city’s free speech-language therapy, immediately test his hearing and see a pediatrician. The pediatrician had other concerns – namely the amount of milk our supermodel-thin fussy eater drank in place of meals – but kicked us on to a private speech-language pathologist and into what I call the land of acronyms and smiling women with toys.

“I’m seeing red flags for ASD.”

What I would give for a video of that first consultation when the speech therapist casually lobbed that grenade. It sailed over my husband’s head and exploded in my gut. I don’t shoot messengers, so I let that life-altering moment pass. Then I walked six kilometres to work bawling and became an autism warrior mom.

Like all parents, I berated myself for missing the signs. As a proud hypochondriac, worrier and worst-case scenario type, I was not in denial. I truly saw nothing.

Have you heard of “joint attention?” It’s code in autism circles for the way that typically developing infants use gestures and gaze to share attention about toys and needs with someone else – and spectrum kids don’t. Charlie was okay at eye contact, but a failure at joint attention.

We got our son to a developmental pediatrician in a record two months after I called in a favour from the grave (thanks dad). He did his first ADOS test – that’s the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – before he was 2. He wasn’t quite on the spectrum.

Not getting a diagnosis doesn’t mean your kid is fine.

We threw Charlie into therapy three times a week and those smiling women with toys changed his trajectory. His social communication therapist taught us how to kick-start joint attention. His new speech therapist quickly moved him from not speaking to three-word sentences. We got lucky. Charlie and therapy clicked. I was sure he aced his second ADOS – fascinating play-based tests with remote-control rabbits, bubble blowers and a mock birthday party.

“Charlie meets the criteria for a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.”

Getting a diagnosis doesn’t mean your kid is doomed.

If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism. And if you’ve read about autism, it’s probably about extreme cases, not borderline ones. The neurodevelopmental disorder messes with communication and behaviour. Everyone on the spectrum has a unique constellation of challenges, and that constellation is in constant flux. Just picture the midway game whack-a-mole.

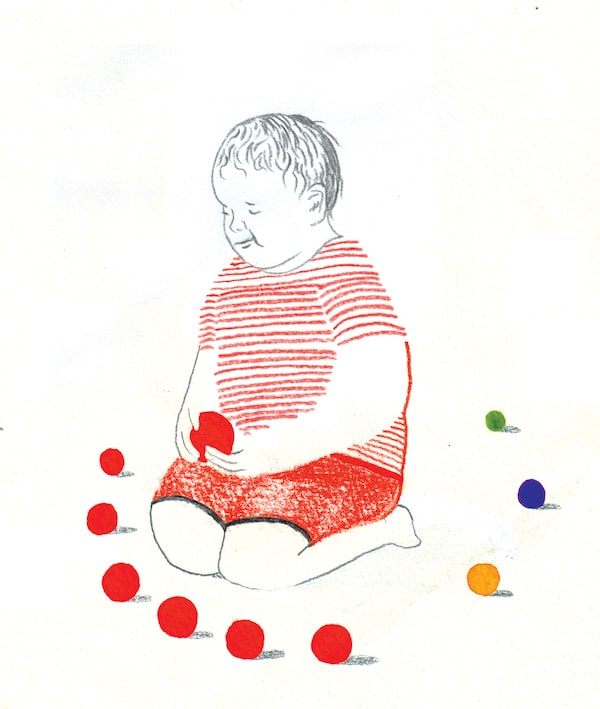

Charlie’s first fixation was on the colour red. He had a collection of red cars and loved lining them up. At a birthday party as toddlers filled baskets with random balls, my son methodically collected only red balls. At another party, he raced around a wildly crowded play place for hours without interacting with anyone but me. He wouldn’t sing Happy Birthday or eat pizza and cake.

You know those multicoloured plastic kids’ plates and cups from IKEA? When Charlie picked a colour to eat or drink from, there was no arguing. That summer we road-tripped when he only ate spaghetti? He’d rather starve than eat macaroni, and he couldn’t cope with the delayed gratification of restaurants or airport lineups. My husband and I quickly learned to take turns going out, hiding our son’s invisible disability by hiding with him inside his comfort zone. We’re only just starting to surface.

“Mommy – how do you talk? Do brains have a voice? My brain tells me to stare.”

Charlie is talkative, silly and clever. He made his first friend last year and even invited her to his fifth birthday party. He invited a different friend to his sixth birthday.

The developmental pediatrician warned that desperate parents mistake plateaus for cures. When social or academic pressures rise, people on the spectrum can crumble. So we cross our fingers and live as outliers on the border of the spectrum. Once a year, I meet with a university researcher who’s tracking how parents navigate the system when their children need help. I get the feeling we are one of the rare success stories (so far).

We got Charlie a new acronym in junior kindergarten – an IEP (public school-board speak for an Individualized Education Plan for a child with special needs). He didn’t need it for the first two years, but just got “progressing with difficulty” marks on his report card for reading, writing, math and visual arts.

Happily, on his last ADOS he dropped a few notches below the line.

Charlie is flexible about the shape of noodle he’ll eat now, but still won’t eat anything that he hasn’t asked for. You can usually find him squatting on a table in the centre of a mess of treasures. He just cheerfully announced he’s never inviting a friend to his birthday party again.

That’s the spectrum for you – baffling.

Jennifer Bain lives in Toronto.