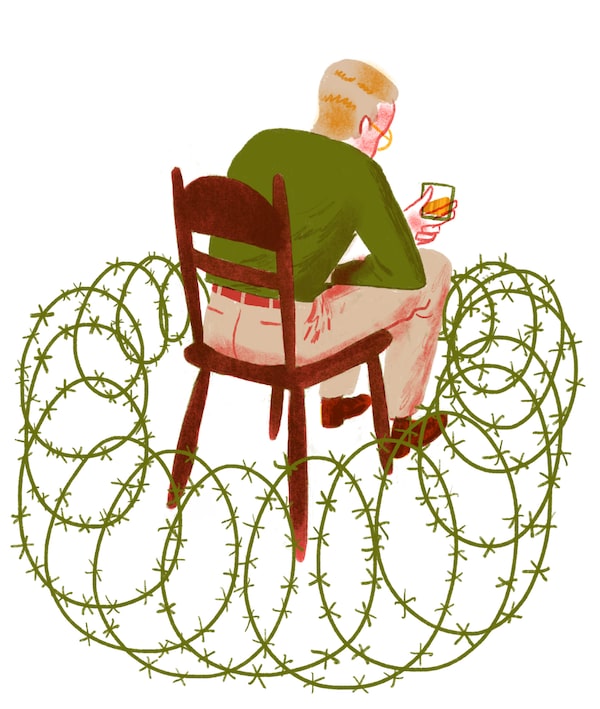

Illustration by Drew Shannon

First Person is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

Sometimes, you get what you wish for and wish that you hadn’t. My mother had always craved information on what her younger brother Ivan had done during his service in the Second World War. Immediately after the war, families often enjoyed a bit of glory reflected on them from having a relative who had served.

We knew our Dad’s part, that he had signed up immediately (good), had trained as a navigator in the Air Force (better) and then suffered debilitating air sickness causing him to be transferred to supply management (not so good). Although this had been a bitter disappointment, he had earned his medals. When we were little, we would watch out the window for him, and we were very proud of him coming home every night in his Air Force blues.

But Ivan kept his role a complete mystery, which irked Mother enormously. She had a keen sense of military hierarchy and what constituted an admirable record. Her mischievous kid brother wasn’t “the first to sign up,” she would quietly admit to family and friends. “But he was on the Normandy beaches during D-Day.” Only a few hints emerged from Ivan, such as his refusal to eat lamb, having sampled greasy mutton once too often. And although he went to the annual Remembrance Day services, he would not join the Legion where war stories were rehashed and embellished. Despite his affable nature and quick wit, Ivan could not be induced to talk about his wartime service.

One fall, when I was a young teenager and Ivan visited our home, Mother hatched a plan. I had been assigned a project on the Second World War for history class, and Mother determined that Ivan was going to be the first-person star of this Remembrance Day story. As a consummate teacher and opportunist, she saw this as a win/win proposition. I would get original and authentic content for my project, and she would have her curiosity satisfied.

As a first step in her campaign, Mom poured Ivan and herself their favourite rye and she produced all kinds of little snacks that she knew he liked: really crispy crackers with smoked oysters, ripple chips and California dip and Betty Crocker’s almond cheese log. Next, she deftly manoeuvred the conversation past his boys’ hockey games, what the fishing had been like that summer and when the hunting season opened. Only then did she introduce the subject of my school project.

Several times Ivan skilfully evaded her inquiries with good humour. As always, he and Mother sparred competitively in the Irish manner. “Well, I know that you never learned to knit socks while our feet rotted,” he accused her, while winking at me. But when she went further, he snapped, “Aren’t you the sleevan, Olive?” As his face reddened, the bluish veins in his nose began to stand out and I watched the twinkle in his eye turn to flint. The verbal barbs kept on, placing brother and sister at war on opposite sides of the fence.

Undaunted, Mother produced more food and drink. Uncle Ivan turned to teasing me about being blonde and he poked about for information on the boyfriends he was sure I must have. After an hour and a half, I wanted to be anywhere but there and I tried to extricate myself. I felt uncomfortable seeing Mother attack as Ivan was retreating. Yet, Mother insisted that I stay because “Canadian history is important and hearing it firsthand is the right of every young student.” After all, she insisted, countering his impish images, “the leprechauns aren’t going to tell us how you got that string of medals.”

Ivan drained his glass and then banged it loudly onto the cherry-wood table, missing both the coaster and the doily underneath. Shocked, Mother did not move to wipe up the spills. Glowering, he looked from her to me. In a monotone he spit it out: “My job was to get the tanks going again when they were sinking in the stinking blue clay of the beach. My buddies couldn’t drive them because the mines were blowing them up. I dragged my best friend out of a tank and he was heavy. His face was blasted off. Lucky to be dead. I dragged out heads separated from bodies so I could get in to get the tanks going again while we were being picked off. Body parts, mud, grease. All my buddies died. Is that enough?” he asked bitterly.

He stopped abruptly and extended his now shaking hand for more Wiser’s Deluxe. Mother had the grace to stop her invasive prodding and give him space to recover before returning to the topic of hockey.

Over the years, I have wondered how Uncle Ivan continued to function, having seen and participated in such horrors. I imagine that he must have had vivid nightmares and flashbacks. Certainly, he passed his visions on to me and I have never been to the beaches of Normandy. Somehow, he worked and carried on with his characteristic good humour until, in his 80s, he had a stroke. Perhaps the answer lies in his determination, for knowing his disabilities and probably bleak future after the stroke, he chose to die by starving himself to death.

I am sure that Mother considered her intrusion into Ivan’s past “a teaching moment,” but for me, it was a much different lesson about the need to protect the pockets of privacy all of us guard. I learned a lot about invasions that day, and I am now the wiser.

Diane Stephenson lives in Ottawa.