At a recent dinner party hosted by an ambitious home cook, the custom cocktail included a homemade soda mix, the octopus was cooked sous vide and the dessert required the use of an iSi siphon. The takeaway: Techniques and ingredients once reserved for high-end restaurants now seem to be commonplace among obsessed foodies.

The modern kitchen, where high-tech gadgets meet a fearless DIY spirit, can give the impression that no task is too daunting and that experts are obsolete. But as anyone who has ever watched a soufflé flop or smiled politely through a skunky homebrew from a well-meaning neighbour can attest, there’s still a place for the pros in our pantries, wine cellars and stomachs. And Canada has its fair share of master culinary craftspeople.

Those below, including David Wood of Salt Spring Island Cheese Company in B.C., Jonas Newman and Vicki Samaras of Hinterland Wine Company in Ontario and Quebec-based Société-Orignal’s Alex Cruz and Cyril Gonzales, represent a geographic cross-section of artisans who not only maintain food and drink traditions but creatively propel the pursuit of delicious summer staples forward. Their focus is intense – and it shows in their products.

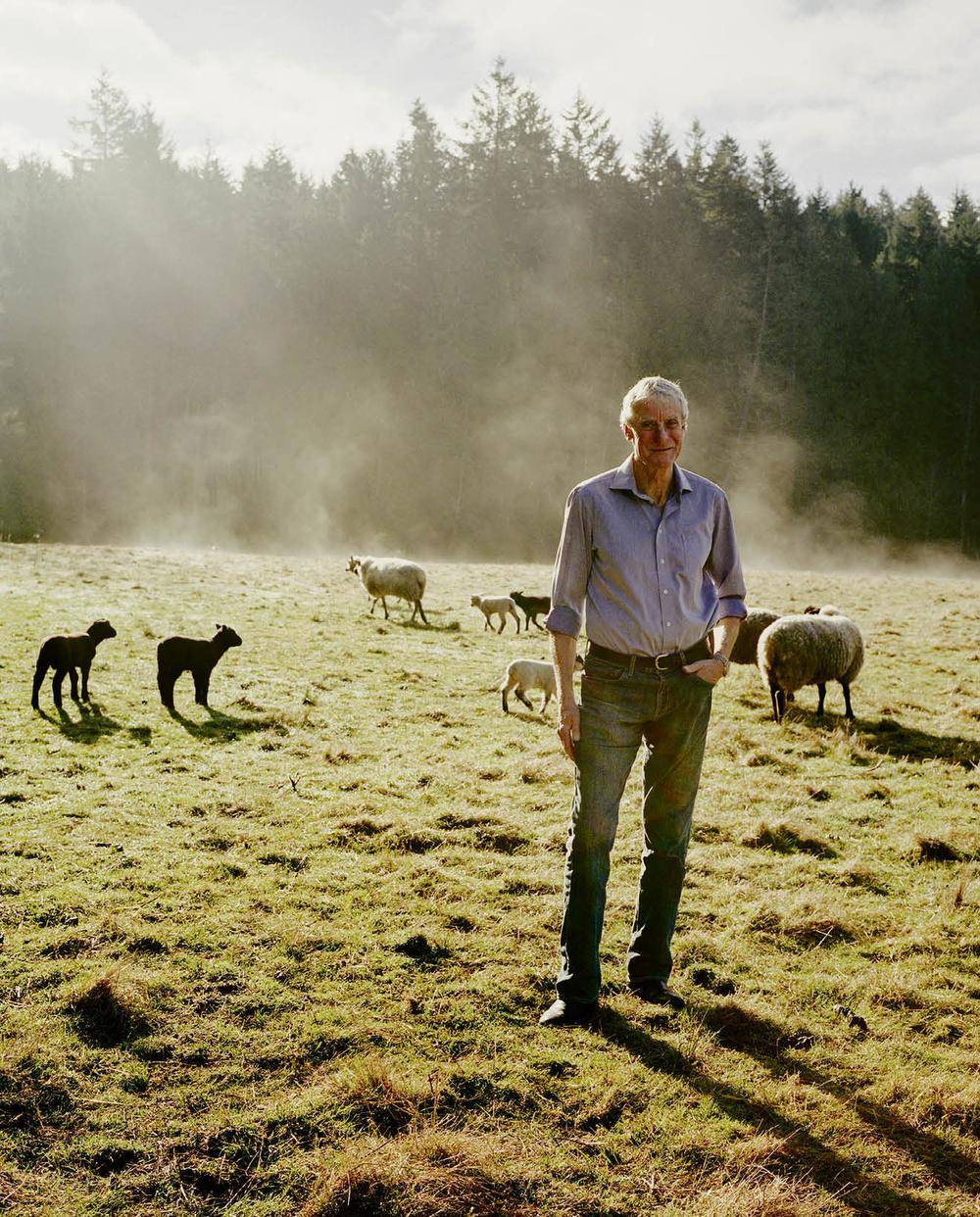

The cheese whiz

The little white mound of goat cheese with the bright flower on top is instantly recognizable to any self-respecting turophile as the gentle, creamy product of the Salt Spring Island Cheese Company. The man responsible for it, David Wood, only started learning how to make cheese after moving to the British Columbia haven in 1990; his first attempts were anything but successful, turning out too strong, too runny or just plain weird.

It was on a trip to Corsica in 1991 that Wood discovered the secret to making the kind of mild, soft cheese he had long aspired to.

“At a small farm up in the hills, I saw that they had added the rennet and coagulated the milk and just left it,” he says. “I asked, ‘How long does that sit there?’ and they said, ‘Oh, two days, sometimes three in the winter.’ A light bulb went off because I realized that the trick to getting the texture out of a fresh goat cheese is to let the curd sit for a long time.”

Patience pays off because the culture in the milk – bacteria called lactobacillus, which ferments the milk sugars – becomes more acidic over time. “At a certain level of acidity, the bonds that hold the calcium in place in the milk break and the calcium starts to leach out of the curd into the whey,” says Wood. “That means you get a very soft, structureless cheese.”

The inspiration for adding his trademark flower (often a pansy, sometimes a geranium or calendula) was inspired by, of all things, an airplane meal. “I had seen a photograph in a magazine of a goat cheese with sprinkled chopped up flower petals and I thought it looked really cool, but I didn’t know how to translate that into a package that can sit on a shelf for two weeks,” he says. “That summer we were on a flight over to the U.K. and I picked up the orange juice container, one of those little plastic tubs with the peel-back foil lid and I thought, that’s it!”

The fizz artists

It’s early summer in Prince Edward County and Jonas Newman, Hinterland Wine Company’s winemaker, is manning the tasting room while his wife and business partner, Vicky Samaras, tends to a cat that’s giving birth in the barn. A French château this is not. But while the setting may be rustic, the wines are anything but. They’re elegant and delicate and gaining ground on the finest sparkling wine produced anywhere in the world.

The young winery’s signature blend, the Rose Method Traditional, speaks to their ambitions. “That wine is the reason that we make sparkling in Prince Edward County,” Samaras says. “It’s our true terroir project and it’s close to our heart.”

“It all starts with the soil,” Newman adds. “We chose the first site based solely on its aptitude for growing grapes. It’s down a dirt road past another dirt road, then across a field just past the mud pile. It’s a great little site. We harvest pinot noir there and it represents between 85 and 95 per cent of the wine, depending on the vintage.”

Chardonnay fills out the rest. All the grapes are hand harvested and whole-cluster pressed, which is the gentlest way possible to handle them. They only use 15-kilogram bins so the grapes aren’t squished under their own weight. Then it’s fermented at a fairly cool primary fermentation.

“Every vintage is different,” Newman expalins. “We ferment 600 litres in small tanks and make our blending decision afterward. Then, in July, we do our secondary fermentation in the bottle and let it rest for at least 16 months.”

“Ultimately, we’re not interested in adding a bunch of things to the wine to make it taste like something,” Samaras says. “It is what it is every year. We try to grow the nicest fruit possible and handle it as little as possible to make the best wine we can.”

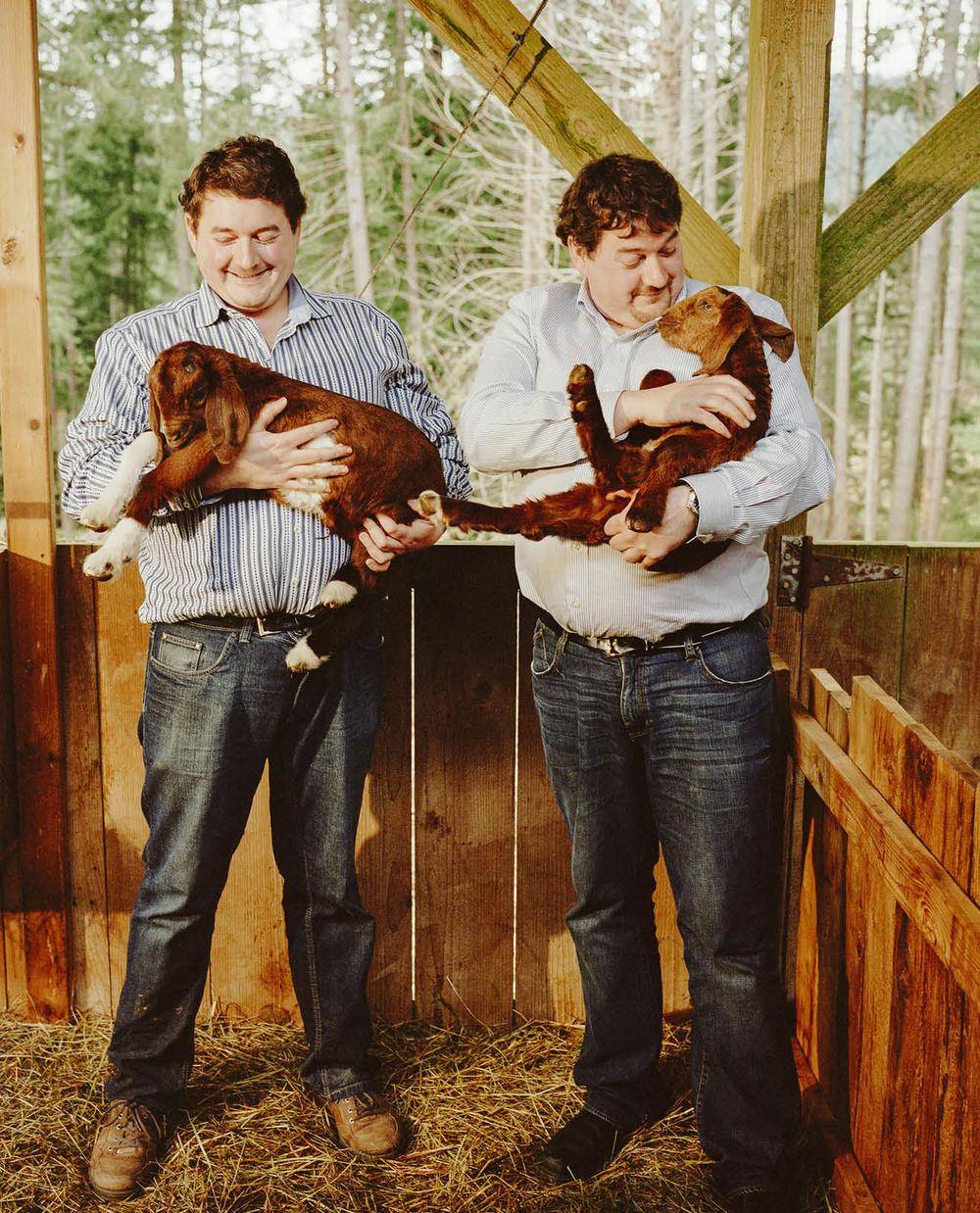

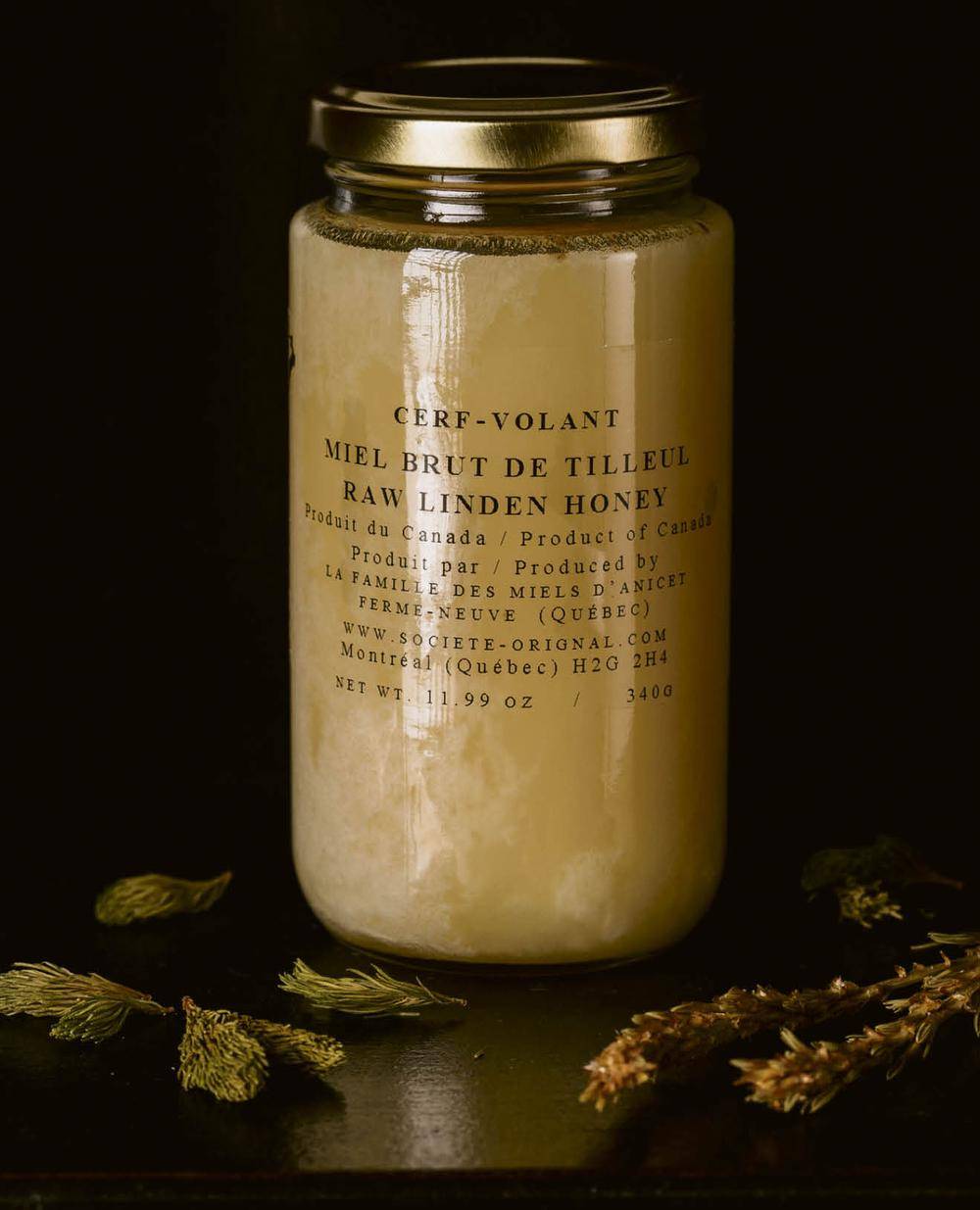

The naturalists

Since launching Société-Orignal in 2012, Cyril Gonzales and Alex Cruz have become known for their work with small independent farmers and food producers throughout Quebec. Their energy and enthusiasm for the small-scale production of ethically raised and harvested goods has helped the company grow from supplying a handful of restaurants in Montreal to being a go-to resource among the best restaurants in North America.

The duo’s earliest projects focused largely on foraged boreal ingredients such as Arctic rose, Labrador tea, day-lily bulbs and all manner of mushrooms. They soon expanded to incorporate more labour-intensive products such as dried sea-urchin bottarga, raw Laurentian honeydew, maple syrup, sustainable fish, a whole line of dairy products and wild game birds.

“A proper flowering of the linden tree only happens once every three or four years,” Cruz explains. “You need lots of rain for four days and lots of sunshine for four days. There’s only a two-day period when the tree flowers, so all the hives are placed and the flowering happens over two days. It’s very concentrated and, after one week, we go back and collect the honey. There’s something sexy about it.”