There were more than 40 people ahead of me in line at Uncle Tetsu’s on a recent sunny Friday afternoon. It didn’t matter. I was going to wait as long as it took to try one of the famous Japanese cheesecakes.

The woman behind me stood patiently with her nine-year-old son.

“This is how much I love you,” she told him.

Mom and son, both avowed foodies – “We had lunch at Mark McEwan’s place,” the boy told me – were visiting Toronto from their home in Aurora, a suburb north of the city. The cheesecake was going to be the trophy they brought home for the rest of the family.

Huge queues have been forming outside Uncle Tetsu’s downtown Toronto location since opening in March. The average wait is more than one hour, while the peak on Saturday afternoons can mean standing for close to three hours.

It is just the latest in a very long line of buzzworthy food items to command huge queues. The latest Apple release will consistently draw diehards willing to sleep outside to be first in line, but nothing attracts lasting hype – and our salivating interest in being part of the tastemakers’ club – quite like food. Whether it’s Cronuts, Japanese cheesecake or soft-serve ice cream made from Quebec blueberries, some of us will go to any lengths for a taste of the hype and the bragging rights that come with it. Smart companies, however, will learn the best ways to manage lineups or watch as customers flee to the next new flavour of the month.

The second time I went to Uncle Tetsu’s, I asked the man in front of me what brought him there. “I’m here because people have been lining up for months,” he said.

To people who study queues, this is an unimpeachable truth: Nothing attracts a line like a line. But there is much more to the field.

The study of queue theory traces its beginnings to 1909. Agner Krarup Erlang, a Danish engineer, was tasked with determining the queuing capacity of central telephone switches in Copenhagen. Too few lines and people would have to wait too long to get a call through; adding too many would be impractical and costly.

Since then, there have been more than 5,000 journal papers based on the hard science of waiting in line, says Richard Larson, a professor of engineering systems at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the world’s foremost expert in the study of lineups (his knowledge has earned him the moniker “Dr. Queue.”)

“There’s a lot of deep math and science behind this,” Larson says.

But since the late 1940s, queue theory has focused on managing people’s perceptions of being in line. We have elevators to thank.

In the postwar period, as skyscrapers were shooting up, people began to complain about long waits for elevators. The engineering solution would be to add more elevators, Larson says.

But then came the a-ha moment. You didn’t have to reduce wait times for elevators. You had to reduce complaints about wait times for elevators. One building added floor-to-ceiling mirrors by the elevator bank as a test. Men would adjust their ties, women could check their makeup. This proved to be a revolutionary move – complaints about waits dropped to nearly zero. It’s a nearly straight line from those mirrors to the flat-screen televisions in everywhere from Tim Hortons to dentists’ offices.

Boredom, or “empty time,” is enemy number one for queue theorists, who fight it by any means necessary.

“Some service providers are known to ask customers to fill out forms that are not actually needed in order to keep them busy and distract them from the wait,” says Ziv Carmon, a marketing professor at INSEAD, an international business school.

Boredom can easily become frustration. “The most profound source of anxiety in waiting is how long the wait will be,” former Harvard Business School professor David Maister wrote in an influential paper on the psychology of waiting in lines. This is why the best practice is to let people know how long they can expect to wait.

Some service providers will take this insight one step further and intentionally overestimate wait times so people are pleasantly surprised it took less time than expected. This is regular practice at Disney, which Larson calls “the Machiavellian experts” in queue psychology.

This was definitely not regular practice at Uncle Tetsu’s, where everyone in line only had a rough idea of how long the wait would be, thanks to social-media chatter and newspaper articles mentioning waits of up to two hours.

Kem CoBa, a hugely popular ice cream and sorbet shop in Montreal, can thank an anonymous Twitter account for taking up the slack in the update department. The account, @KemCobaLine, regularly tweets how many people are currently in line at the shop. Occasionally, there are photos. One, from last month, showed a queue of more than 60 people wrapped around the block.

Uncle Tetsu’s has a similarly dedicated Twitter account, run by someone who isn’t affiliated with the company, either. Every one of its tweets has the date, time and a photo of the queue. Tetsu should send this person a free cheesecake every week.

Of course, when you’re selling the hot item of the moment, you can ignore the fundamentals of queue management. Bang Bang Ice Cream and Bakery, another Toronto hot spot, has epic lines lasting half an hour or more on the regular. People who join the line have no idea how long they will end up there; they just know that they’re about to get ice-cream sandwiches described as “a religious experience.”

Ultimately, people will come no matter what to see what the buzz is about. We want to see if the experience lives up to the hype, but we also want the social capital.

We’re not just buying a cheesecake. We’re buying a great anecdote.

Nancy Petch, a woman I met in line at Uncle Tetsu’s, told me she was in line to surprise her sister with a cheesecake that evening. She said she knew it would also make a great topic for dinner-party conversation.

“Food is one of the most popular things people talk about,” says Jonah Berger, author of Contagious: Why Things Catch On.

The social capital that’s sought after in joining queues at Kem CoBa or Bang Bang helps explain why people are so prone to taking selfies and tweeting or posting other social-media updates while they’re in line. It’s broadcasting to your social circle that you’re doing this cool new thing, Berger says.

“It allows us to show we’re a little bit ahead of our friends,” he explained. “We like to be a little bit ahead of everyone else.”

Larson is more blunt. “It’s a little bit of bragging rights,” he says.

Larson made another interesting point. He told me to ask people in the queue at Uncle Tetsu’s and Bang Bang how many times they’ve waited in line before.

“My hunch is, most of them would say none,” he said.

He was right. In two trips to Bang Bang and another two to Uncle Tetsu’s, everyone I spoke to was there for the first time. Once we’ve got the bragging rights, we have better things to do with our time.

“Probably three years from now when the thing is three years old, those kinds of lines will disappear,” Larson said.

They can disappear for many reasons. More stores open to serve demand. Tastes change. Someone cooks up the next hot new thing.

Some places, such as Schwartz’s, in Montreal, become institutions. Most others follow a similar trajectory to that of Krispy Kreme donuts. It starts with hysteria and ends in indifference.

Dominique Ansel, the inventor of the Cronut, is fighting that fate. Rather than ignore the basics of queue psychology and coast on buzz, as he easily could at his New York bakery, Ansel is trying to build customer loyalty, starting with the lineup.

“We always try our best to make sure everyone has a great experience from the moment they arrive,” Ansel said in an e-mail. “We serve everyone warm madeleines that are right out of the oven, as well as lemonade during the warmer months and hot chocolate when it’s cold out. We’ve given out hand warmers and umbrellas, and really take great care in making sure we service our guests each and every morning.”

Every 15 minutes someone on staff goes out and greets guests, sharing details about what the flavour of the month is and answering any questions people might have, Ansel added.

People in line don’t get estimates of how long the wait will be because it varies too much, he said.

It’s a smart choice. We are delighted when a wait is shorter than expected; we get disproportionately peeved when it’s longer.

In other words, Ansel is incorporating the best insights from queue theory to keep customers coming back.

Giddy first-timers, however, will wait happily as they anticipate just how good this thing is going to taste, whether it’s a Cronut or a cheesecake.

“That can sometimes be even more enjoyable than the actual experience,” marketing professor Carmon says. “After all, it is unlikely that you will be disappointed during a fantasy, whereas in real life things often don’t work out the way you might have hoped.”

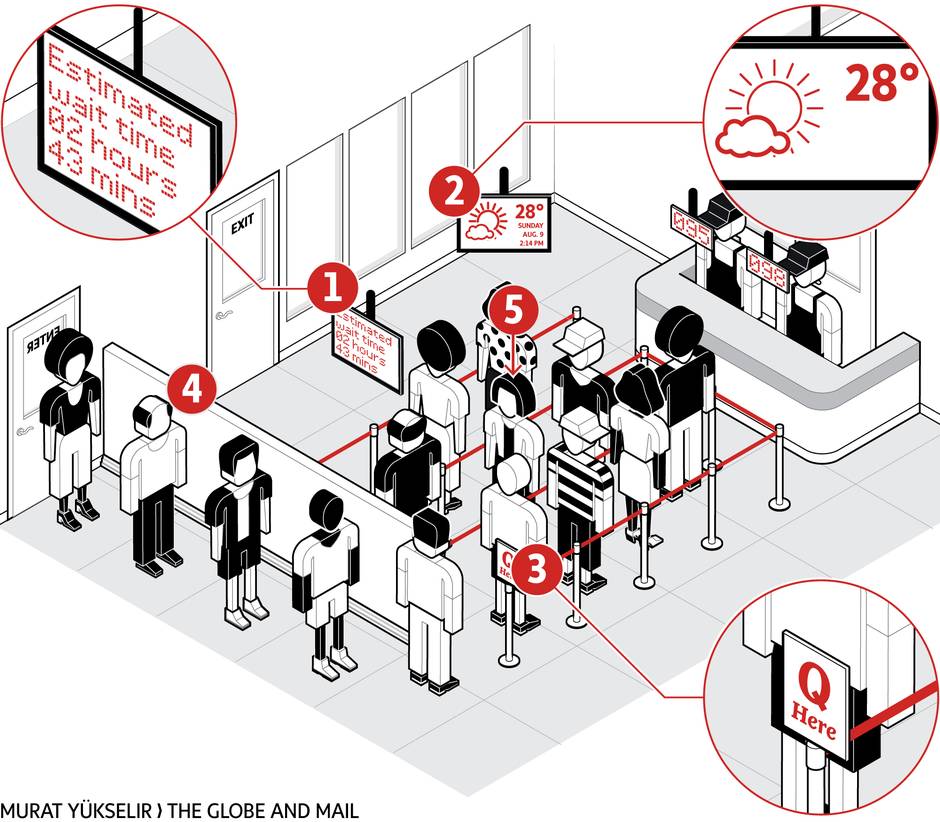

The anatomy of a lineup

1. Uncertain waits feel longer, and thus create more frustration, than waits of a known duration. To improve customer satisfaction, some queue managers broadcast over-estimated wait times to those in line.

2. To help prevent boredom, frequently caused by “empty time,” some type of distraction, often a screen, is provided to keep your attention off the wait.

3. Wendy’s and American Airlines both claim to be the first to adopt a single serpentine line, which is perceived to be more fair than multiple lines. It also means you can’t be angry when another line looks to be moving faster than yours, because there’s only the one line.

4. Queue length often determines whether people will join it. People will choose a short line that is moving slowly over a long line moving quickly. Queue managers will often disguise length by wrapping it around walls or having it zig-zag.

5. The more people there are behind us in queue, the more we value the thing we are waiting for, according to researchers.