The past decade has been soaked in bourbon, and it's easy to see why. It tastes like sweet, boozy, butterscotch-ripple ice cream and the price point is decent compared with Scotch.

But the biggest reason for a renewed enthusiasm for the corn-based spirit, however, has been its marketing, which trades on the idea of a hand-crafted product with a long-established heritage.

Tradition, however, is a tricky concept, easy to look at through rose-coloured glasses. But when you take a step back, the bourbon-based lionizing of heartland values, American pride, chivalric gentlemen and simpler times is, to anyone with a knowledge of history, deeply unsettling.

Take the mythology of Tennessee or Kentucky's "whisky trails." They are both period pieces stubbornly populated by stock characters such as frontiersmen, salt-of-the-earth types and roguish moonshiners similar to the Confederate flag-flying Bo and Luke Duke (no relation to David, that we know of).

Some distilleries, such as Woodford Reserve in Versailles, Ky., let visitors tour a quaint, miniature version of their operation located in a pretty, pastoral setting before they hit the gift shop to pick up a bottle of hand-crafted, small-batch, brown liquor.

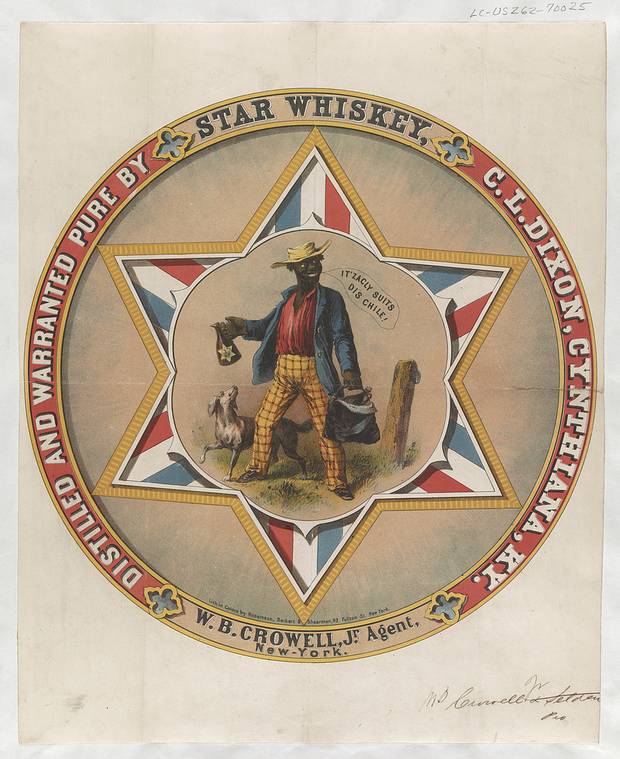

Whisky’s racist advertising of the 1850s exploited the tropes of minstrelsy that portrayed black people as lazy, simple-minded buffoons.

U.S. Library of Congress

That liquor may or may not have been made on site, since the distillery has another large, loud and presumably less appealing facility nearby that's not open to the public. The overwhelming majority of American spirits is mass-produced; packaged, distributed and sold by multinational corporations. The most egregious part of this story isn't that lie, though. It's the fact that the region and industry's sales pitch constructs a mythology that fantasizes about a glorious past that was built on racism, oppression and violence.

The golden age wasn't particularly golden for those who experienced the lynchings and daily terrorism that was part and parcel of the era being idealized. African-Americans know this, which is why bourbon has never sold terribly well in their communities. Around the turn of the previous century, gin was what they preferred. And ever since African-American soldiers from Jim Crow-era southern states were deployed to fight in Europe in both wars, Cognac has been the most popular liquor among African-Americans who could afford it.

Derrick Willis, an anthropology professor at Illinois's College of DuPage, sees this as a souvenir of the experience of having been treated humanely in Europe, a stark contrast to how black soldiers fared at home. "So, when they came back to the United States, they drank Cognac as a way of symbolically standing for a different type of possibility of race relations," Willis says. "It was a very different interaction with whites and a very peaceful co-existence in which they felt respected as equals."

Although not every millennial African-American who likes Hennessy is aware of the history, Cognac's popularity in hip-hop culture can be traced back to this transatlantic experience. Well, that, in combination with whisky's racist advertising that, starting in the 1850s, exploited the tropes of minstrelsy that portrayed African-Americans as lazy, simple-minded buffoons. After the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, these images evolved into depictions of ecstatically happy African-American house servants eagerly serving up bottles of Kentucky bourbon.

This is the golden age that the golden-age-of-drinking sales pitch is pinned on. It might come with a pretty handwritten label on it, but the mythology it's selling is just as racist as the minstrel show. It's just a modern, more polite incarnation, which, as of last week, just became a whole lot less polite.

Essence of Old Virginia Wheat Whiskey, A.M. Bininger & Co., 1859

U.S. Library of Congress

"Golden-era marketing dovetails with the phenomenon of what just happened with this election, with a president who says he's going to make America great again," Willis says. "Great again for who? For the white men who felt marginalized, bourbon does represent that. You know what they say: The past isn't dead. It isn't even the past."

Which brings us to more recent allegations of bourbon-soaked racism, too. In 2012, Maker's Mark dealt with charges of discrimination when it was accused of having refused service to a party of African-Americans in one of its Louisville, Ky., facilities.

Earlier this year, Jack Daniel's performed an astonishing act of cultural appropriation when it began celebrating the revelation that charcoal filtration – the patented process that sets Tennessee whisky apart from other American whiskys and made Jack a mint – was pioneered by Nearis Green, a slave. (No news release thus far, though, about Lem Motlow, Jack's nephew and protégé, who got off on murder charges in 1924 with a defence that the African-American he killed didn't know his place and, therefore, had it coming.)

Discovering that a southern U.S. institution has a racist past is, sadly, not shocking, and this isn't necessarily a call for a bourbon boycott: Switching to Cognac doesn't necessarily solve anything because many are owned by parent companies that also sell bourbon.

It's simply a warning to be careful which myths we choose to swallow. Underneath all that sweet butterscotch flavour, some of them have a deeply bitter taste.