It was winter and near darkness when my grandfather, John Fox, threw open the front doors to the now infamous Pelican Lake Indian Residential School and strode straight to the infirmary. He was there to save his son's life. He recalled how horrified he felt when he walked into the room to find a handful of young boys, his included, looking gaunt and near death. It was 1944.

Despite threats of incarceration by supervisors and staff, my grandfather gently wrapped his eight-year-old son in a blanket he'd brought and slung him over his shoulder. "He was skin and bones," my grandfather later recalled.

And then he ran. Across Pelican Lake to a cabin in the bushes, tucked away from glaring searchlights. He waited there until he thought it was safe to run again. This time, he ran for the Sioux Lookout Zone Hospital, a federally run "Indian" hospital. It wasn't far by vehicle – only 15 minutes east of the school – but this was winter, and my grandfather had no vehicle.

He kept thinking about the boys he'd left behind, lying there looking grey and shrunken. For many years after, he would run into some of the boys and ask about them, only to be told they'd died.

They made it to the hospital in Sioux Lookout, and shortly after, the boy – my uncle Bob – was airlifted west. He vaguely remembered travelling through a snowstorm, but beyond that did not recall anything until he woke up on a summer's day. He believed he was in a hospital in Winnipeg but was never really sure. He spent two years there recovering from near death. He said they were fed rotten food at the school, and that's what made them so sick.

"I would have died that night," he later said, "if the old man hadn't come and got me."

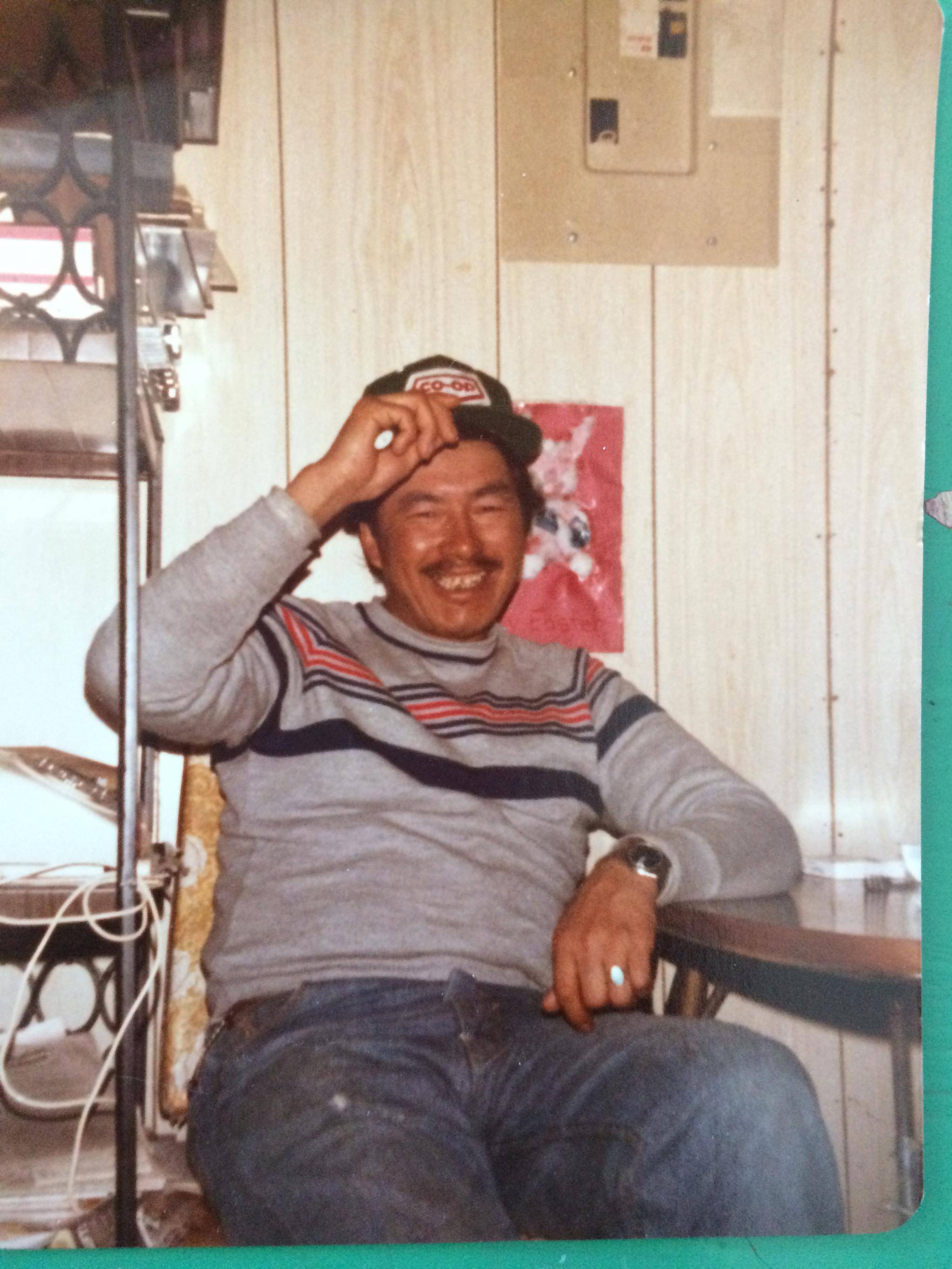

Both my grandfather John and uncle Bob have since passed away, leaving us with countless stories such as this one, which have been passed down through our grandparents and parents.

My uncle didn't know how his father knew he needed to be rescued. He just assumed someone, somewhere between Ontario's Sandy Lake First Nation and Sioux Lookout, told my grandfather that his son was very sick. But our family also knows how intuitive my grandfather was.

This is the story, among others about my family's dealings with the health-care system, that I carried as I read Gary Geddes' new book, Medicine Unbundled: A Journey Through the Minefields of Indigenous Health Care. Each story contained within resonated with me. Each story unfolded without surprise. And still, each story hurt.

Medicine Unbundled takes readers across Canada, carefully and achingly sharing the memories of survivors who underwent non-consensual drug and surgical experiments. Survivors who were segregated and denied health care afforded to mainstream Canadians. It's a difficult read but doesn't leave you feeling hopeless. Rather, it points to something ugly and painful and says: Look at this history – now let's do better.

My name is Adrienne Fox. I'm a mother, a member of Michikan Lake First Nation in Northwestern Ontario and a storyteller (a journalist by mainstream definitions). I use photography, video and writing to tell stories about people in my part of the country, which happens be Northwestern Ontario, land of the Ojibwe and Oji-Cree.

I spoke with Geddes by telephone this month from his home in British Columbia. We spoke about the not-so-distant past. About the health-care and education services provided to Indigenous people in Canada. And how both sectors were used as tools by the Canadian government to slowly eradicate the "Indian problem." Fortunately, the government forgot to factor in one crucial trait: resilience.

From your research, what do you think the driving force is behind "Indian hospitals"?

Well, Indian hospitals were not set up to help Indigenous people. They were really set up to help keep them separate from a white racist society and, as such, they were on such racial foundations, it's not surprising that they were underfunded and with some notable exceptions, poorly staffed.

The government actually bragged. Then-prime minister John A. Macdonald bragged that he was keeping the Indians half-starved, and Duncan Campbell Scott, the deputy superintendent of residential schools, took some pride in saying, "We can run these hospitals at 50 per cent of the cost of health care for other Canadians." Pretty shocking stuff.

What do you say to people who say these hospitals were well-intentioned?

Well, most health care is supposed to be well-intentioned, and I'm sure there were some people in those systems who were doing a good job. But given the racist foundations, they weren't doing what a normal hospital would try to do. And with limited funding and so on. And they were subject to a lot of the systemic racism we still have. People say to me, "Hey, this is all in the past, none of this is going on any more." But it is still going on. In Winnipeg, for example, Brian Sinclair, an Indigenous man, died in his wheelchair in an emergency room after waiting 34 hours unattended with a kidney infection that could have been treated with antibiotics. So he was a victim of what I actually call psycho-cultural triage. Somebody looked at him and said, "Oh, this is a drunk Indian or just somebody trying to get warm off the street," and they ignored him. They ignored him to death basically.

Joan Morris, a Songhees elder and the one who set me on this path, has a lot of experience in the health-care system. She was a nurse's aide most of her life, and as a young woman she went in to have an internal examination which turned out to be very painful, so she complained to the doctor. And he said, "Oh, come on, Joan, you Indian women like it rough." I said, "Joan, how did you resist poking her in the nose?" And she said, "I didn't want to stoop to her level." I said, "Is this stuff still going on, 40 years later?" She said, "It sure is." I've heard this kind of thing time and time again.

So what do you hope your book is going to do in the long run?

Well, hopefully, what it will do for others is what it did for me. And that was to open my mind and eyes and teach me a lot about what's been going on. I hope that Canadians can embrace the real truth of their history, as I'm trying to do, and realize that what we've been involved in is a slow-motion genocide.

I think it's really crucial that we take into our bones seriously the [Truth and Reconciliation Commission] revelations and the health-care revelations, which I think are the missing chapters in our book of failed promises in our obligations to Indigenous people.

From everything you've learned and from everybody you've listened to, what do you think can be done to improve health-care delivery to First Nations people today?

It hasn't been my aim to provide too many answers to that because it's Indigenous people that need to be the ones that determine what they need. But what I have seen in a few cases is that some steps are being taken that are really promising, like in British Columbia. There's an Indigenous health sector in the regular health system and that's enabling a lot of First Nations nurses and supervisors and bureaucrats to get out into the reserves and use their basic knowledge and their contacts to find out what people need.

And in Saskatchewan, there's an all-Nations healing hospital that I went to which was really exciting and it had a sweat lodge. It had rooms for prayers and things for folks who were saying goodbye to those who passed away and could be with family who were in the hospital. Huge, huge rooms for people, so that large groups of family could come into visit. So there are some things happening.

How has this, working on this book, how has it changed you?

Well, it's been difficult, and there were times where you almost feel you're suffering from secondary PTSD listening to these stories. But I had to remind myself that however painful this was for me, it was infinitely more painful for those who'd been through it. But the issue with how to present this material was a challenge, too. You don't want people reading the book to be running out looking for a razor blade. Or to get so depressed they just close the book.

Joan Morris kept saying, "Gary, the problem I have with white people is that they don't listen." So I wanted to make sure I listened very carefully to all these stories and picked up not just on the pain but on the humour and the courage and everything else that went with it. So that's what I've tried to do.

You touched on it a little bit earlier – about the legacy of these hospitals. Where else do you see the legacy of those hospitals in today's health care?

Well, there are several ways that manifests itself. One is the fear that people have of going in to get treated. If they know they're going to get a racist response, they're just going to delay for as absolutely long as possible before getting medical advice.

That's one of the things, and sometimes you go in and the doctor has already got a predetermined notion of what your problem is and it's often based on racist assumptions. And so Addy, who was Joan's aunt, never got treated properly because on her records there were assumptions in her medical records that the doctors looked at and just came to conclusions and didn't treat her properly.

She had black stools, she had stomach pains, and they just told her that she had constipation and sent her home again. And it turned out after several visits to the hospital that somebody did a proper examination and she had two stomach ulcers. And the doctor said to her, "How come you've let yourself become such a tub of lard?"

Comments like that, you know, it just … I've heard this many times, and I just recently visited Joan Morris in the hospital again, and she was in a very bad mental state because she felt like she was being totally ignored by the nurses and that they'd probably looked at her medical charts from one hospital that made certain assumptions and were not paying much attention to her.

And then the larger question, well, I don't know if it's the larger question but an equally important question for Indigenous people is that the whole system tried to destroy both the culture and the medical knowledge. People were told it was all witchcraft. Even all their centuries-old knowledge of certain plants with their medicinal qualities was rubbish. They were put in terror of the new system and made to no longer trust their own. And that's just two of the things. I'm sure I could come up with a few more.

Can we go back to when you mentioned psycho-cultural triage. Can you expand on that a little more?

Well, you know what the term "triage" means – when doctors are faced with massive injuries and they have to look at 20 patients and decide who is the most critical, who is likely to die – ignore that person – who is likely to live a longer life by quick examination – that person is second choice and the person that's most likely to survive gets immediate attention.

I've probably misrepresented that, exactly, but I just took that term because I was talking to some nurses at the University of Calgary and I thought it would be interesting to talk about psycho-social triage, which is the racist assumptions that are in people's minds when they go into the emergency room. And the receptionist who is supposed to be taking the information who looks at you and unconsciously or consciously has these assumptions about Indigenous people which determine whether or not she takes it seriously and puts down whether it requires immediate attention. So it's just another – a catchier term for the kind of racism we were talking about based on stereotypes.

I have your book here in front of me, so I'm just going to pull out a passage that stuck for me, this one about privilege and coming from a place of privilege. From when you first started this project to now, how have you contemplated it or integrated the knowledge that you come from a place of privilege when you're writing and working on projects such as this?

Well, I've put in four years of my life now without a penny of support doing this thing. So for me, it's been a challenge and a pleasure giving something towards the telling of the story. And I'm aware, I grew up in a very poor family.

We lived in this sort of slum apartment on Commercial Drive in Vancouver. There was no money. Sunday dinner might have been fried bologna, and I learned early that some people live in privilege and we weren't in that group. But I have since been very lucky and had a career teaching in universities and had all sorts of good things happen to me, so even when I try to get some mileage out of my slum origins, I have to acknowledge that even there on Commercial Drive, we were eating. It wasn't very good, but we had a roof over our heads. We didn't have mould to contend with or polluted water or anything like that, so I'm part of the privileged world of colonialism in this country.

So I think very seriously about all this stuff. I might have thought even more seriously about it as a child, knowing about privilege even then, if I had been taught anything about it in secondary school or primary school. But all there were were the clichés about drunken Indians and so on. Nothing about what our responsibility was for this situation.

Well, I'm First Nations. I'm from the region here, Treaty 9 in Northwestern Ontario. I've had a lot of experience or too much experience with the health-care system, which hasn't been great, but I think even living in a small town like this hasn't been probably as bad as it has been up North, where your front-line workers are nurses. You don't have access to doctors like we do here in town. We might have to go sit in the emergency room and wait for three or four hours, but eventually we'll see a doctor.

Yeah it's an interesting time. [Former TRC head] Senator Murray Sinclair said it's going to take seven generations to heal, and what makes me feel ill is the thought of all the young people who will be lost during that time. That's unbearable to think about.

Yeah it is. We've had a lot of suicides in this region and we've had a lot of kids go missing and unexplained deaths because a lot of the communities don't have high schools yet. So a lot kids have to travel to urban centres to get their education.

And the official apology has done very little, more like lip service than anything else.

Absolutely.

A serious apology would have immediately put in place a huge number of protections and things like that.

My hope for the future is pretty dismal. At least in my lifetime, or even in my children's lifetime, I think we're still going to be fighting to have our space back. Because right now, we don't have our space, and like you mentioned in your book, the only time we're taken seriously is when white academics or scholars start recognizing an issue or talking about an issue – then it becomes legitimate.

It's certainly true. And I've heard this from nurses and people within the Indigenous health system in British Columbia: "Yeah, it's easy for you guys to get published, but it's much harder for us to get published."

Is there anything else that stands out for you from all the research that you've done? Is there anything you learned that kind of changed you on a fundamental level?

Well, I guess what I've learned is the incredible resilience and the reservoir of wisdom amongst Indigenous people, and that is something that the whole country needs at this moment as we see the planet going downhill. We need that kind of wisdom that involves the Dakota phrase "all my relations." And the fact that Indigenous culture has accepted the notion that everything is interrelated.

The boom-and-bust psychology of colonialism does not recognize that at all. And that's why we're in such a terrible state on the planet. So for me, Indigenous knowledge is so important. We all need to get back to it right away.