'The governments of this country, federal and provincial, have turned to family caregiving as the go-to solution for those struggling with mental illnesses," Calgary author Clem Martini writes. "But what happens when that solution collapses? What happens when caregivers grow too old to provide care, or get ill and require care themselves?"

The answers are frightening, chaotic and heart-breaking, Clem and his brother Olivier Martini reveal in their new memoir, The Unravelling. And with a growing number of families encountering this very scenario, they suggest, the need to address these questions is urgent.

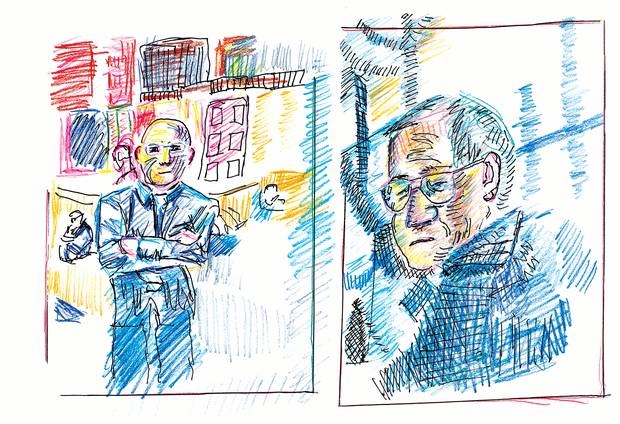

The memoir, told through text by Clem and illustrations by Olivier, recounts their family's desperate scramble when their mother, Catherine, develops dementia. Between refusing to shower and protesting her move to a hospital, Catherine sobs as she worries about who will remind Olivier to take his pills. Meanwhile, living on his own for the first time in decades, Olivier eats two bananas for dinner and stares absently at a broken television set, feeling lonely and guilty that he let his mother down.

The family's ability to take care of one another had long depended on a delicate balance. For nearly 40 years, Catherine and Olivier lived together. She supported him as he struggled with schizophrenia. He, in turn, provided companionship and helped her as she became increasingly frail.

But when it becomes clear she can no longer maintain her role in their collaborative care, the family seeks professional help, only to encounter red tape, overworked health workers, overcrowded facilities and, often, more frustrations than solutions.

As with their earlier book, Bitter Medicine: A Graphic Memoir of Mental Illness, which won accolades including the City of Calgary W.O. Mitchell Book Prize, The Unravelling is a candid, painful and, at times, comical account of what it's like to navigate a perplexing health-care system that fails to meet the needs of the patient.

Clem, a playwright, screenwriter and novelist who teaches in the University of Calgary's drama department, spoke with The Globe and Mail by phone.

You mention the term "caregiving" didn't really fit for the relationship between your mother and Olivier. Can you explain?

People think caregiving is a simple procedure. There's someone who gives care, someone who gets care. And it's not that at all. First of all, there's generally many people involved. In my family, my oldest brother Nic and I are part of that caregiving team.

In addition, it's not as simple as give and get. My mother got something from it, too. As she got older and frailer, it was sometimes difficult to say who was providing and who was getting more care.

There was a switch that happened and it was dislocating for all of us trying to figure out how to negotiate that transition. Everything kind of fell apart and was perilous for a number of years.

What were the first signs your mother's cognitive abilities were declining?

In retrospect, there were small signs along the way. I used to visit them every Sunday morning and we'd all have breakfast. One morning, she put what was supposed to be a waffle in the toaster, but instead, it was garlic toast. And she put it on a plate and poured syrup over it. She didn't notice at all. She didn't know the difference.

There were all kinds of other issues at the time. She was falling often, but she was adamant in her desire to stay at home.

The biggest sign was after Olivier had gone into the hospital after an extreme reaction to his drugs, I came to check on her and to talk about my brother's situation. She had been expecting me. But when I got there, all the lights were off and I found her standing naked in the washroom. She didn't know what was going on. She just kept looking in the mirror, going, "Something's wrong."

While trying to figure out how to care for your mother and brother, what measures did you take to take care of your own health?

You know, in a crisis, you tend to deal with the things that are most urgent. And in a situation like this, there's all kinds of urgent urgencies. You have a mother who is rapidly descending into dementia. Her bills aren't paid. Her cleanliness is impaired. Her ability to understand how to conduct herself is failing. Her safety is at risk.

My brother's care was also urgent. He was obviously depressed. And when one is dealing with a mental-health condition, it can rapidly go south. Because my youngest brother killed himself and because Olivier has at times been suicidal, you never know when things will go from bad to critical, so you have to deal with that.

So there were times I didn't know what to do. I didn't know how to find time for myself. I finally decided I had to get out of the city and out of the head space I was in, so I took a road trip to a provincial park and tried to find exactly where I was in that process. I also called and talked to a therapist on the phone. I didn't find that particularly productive, but I tried to figure things out for me.

What advice can you give to others who find themselves in a similar position?

Reaching out to friends and family helps. I would certainly talk to my wife and to a degree, to my children. But you want to be careful not to make a bad situation worse. You're trying to find support and find ways to remain sane and all of that, but you're trying not to create a problem for others.

Try to find supports at work. I told my employers what was going on and that there were times when I'd have to step away from work. They understood that. Being transparent about the situation is important. And where it's possible, getting professional assistance can be useful as well.

You give readers a vivid sense of how frustrating it was to deal with certain health-care authorities. But why were you so cautious about not letting your anger and resentment show?

Regardless of how irksome or frustrating you may find things, you cannot make the situation worse for those in care. And it's possible for that to happen. If you go to a long-term care facility, you can see people are stretched very thin. They're understaffed, they're often overwhelmed. And if you are the problem, it may be reflected in the way your parent is dealt with.

I've seen that with my brother, too. Because there is no clear protocol about family caregiving, often, you're seen as an extra. You want to be sure you maintain whatever ability you have to be a positive influence. Otherwise, you can create problems for the patient, or you can simply be cut out of the loop.

How is the system of care for the elderly skewed in favour of those with higher incomes?

There's an enormous number of people who, at this juncture, are becoming aged and infirm. There are public and subsidized residences, but there isn't near enough room in those to accommodate all the people who need that subsidy.

Private residences – and there's difficulty in accommodating people there, too – can be very, very expensive. So if you don't have enough money, you may be compelled to wait a long time. And when a person's situation becomes critical, there is no time. They cannot be accommodated at home, they cannot take care of themselves. What are the options?

We have to think about the practicality of it and we have to think about the justice of it.

The standard of care is also something to think about. The private facilities can pick and choose who they take. They can say, "We don't want to deal with people who have severe dementia. That takes a lot of manpower and that drains the profit margin." That means in publicly funded ones, you often get the most needy, the most troubled all in one facility. Well, that's a different environment.

What is that environment like?

I've walked into facilities where it's very sad. There's people in wheelchairs crying, sometimes begging to be released, sometimes heavily medicated, and very few staff.

First of all, that's not good care. Second, suppose you went in to that facility with some cognitive abilities. How is that serving you to be in this environment? There's no ability to socialize. No ability to make the last years of your life social or healthy.

You describe how confusing and opaque the whole process was to get your mother into a care facility. In an ideal world, what would that process look like?

In an ideal world, it should be transparent, it should be aware of the person's situation and it should be quick. None of those things are true right now.

Above all, the transparency of the system is quite negligent. There is no transparency. I would ask, "How does this work? How does a person get selected? What's the list and who makes the choices?" And I never got a clear answer. Never. In fact, whenever I asked, it wasn't seen as me trying to get information. It was seen as me trying to stir things up. So I would have to try to go along with this system that is like a roll of the dice on some deranged board game.

There seems to have been a general lack of care in the health care given to both your mother and your brother, with exceptions from certain individuals such as your brother's psychiatrist, Dr. Baxter. What was she doing right?

There's a real lack of understanding or respect for family caregiving within the mental-health system. Some psychiatrists won't pay any attention to the family at all. But that wasn't true of Dr. Baxter. She was very welcoming and understood that family support was important to Olivier. I was pleasantly surprised when she invited my eldest brother Nic and I to attend a session at her office with Olivier. It was helpful for Olivier, who was her main focus, but it was helpful for us, too.

And I had never heard of a psychiatrist doing house calls. When she said to Olivier, "Okay, you want to maintain independence. Great! I'll come over to your apartment and take a look. We'll have tea and we can talk about what's going right and what's going wrong," it was 100 per cent right. It was treating Olivier as an individual. It was reinforcing him, it was inviting us in on that and it was practical. It wasn't us offering a report about him. It allowed her to go, "This is where you seem to be taking care of things and here is where you need help."

It was practical, it was thoughtful and it acknowledged the kind of teamwork that was involved. It was unique in my experience.

You mention you had some apprehension about telling this story. Why?

In the made-for-TV-movie version, things get bad and then things get good, and everyone learns a lesson. In my experience, it's not like that. Things get bad and things get messy and embarrassing and you really struggle. Sharing that with people makes you vulnerable and makes you anxious that you'll be judged. When you talk about the inability to deal with hygiene, that's awkward.

The interesting thing to me is when you do talk about these things, how many people will say, "That was my experience, too. That happened to me and my mother and I didn't know how to deal with it." It's only through really sharing those moments when you feel vulnerable that you can connect with others and make them understand they're not alone.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Book excerpt

A drawing by Olivier Martini excerpted from The Unravelling (Freehand, 2017).

Shortly after breakfast, Mom begins her move. A nurse helps her into a wheelchair and loads her into an ambulance. I assemble her small collection of possessions and drive ahead to meet her.

She will share a bedroom. Her future roommate neither speaks nor moves, and appears unaware of her surroundings. In another time and place, this would be distressing, but in the short term, at least Mom will have little reason to complain about her neighbour talking too much, crying too loudly or stealing — all things she complained about previous roommates.

Her bed and bureau are located next to the courtyard-facing window, offering full access to the natural light of the courtyard's skylights. She likes that. The window opens a crack, allowing air from the garden to circulate. She likes that as well.

While she meets with the physi otherapist — a pleasant, patient woman who appears to be in her last trimester of pregnancy — I slip downstairs to the director's office to fill out forms, organize payments, and set up an incidental account that Mom will be able to draw upon for purchases at the tuck shop or the residents' hair salon.

When I've completed the paperwork, the director takes me to the physiotherapy room, where my mother is arguing with the physiotherapist. Given how unsteady Mom is on her feet and prone to falling, the physiotherapist would prefer that Mom use the wheelchair she was brought in on, but it's a point of pride for my mother that she stand and use her walker, chug along under her own steam. The physiotherapist catches my eye and when I shrug, she acquiesces.

Miriam, an attendant I'd met earlier when I first arrived, peeks in to announce lunch. We exit the physiotherapy room and form a bit of a parade, Miriam leading, my mother following, and me taking up the rear. My mother shoves her walker vigorously ahead of her, defiantly independent, if going at a snail's pace. We eventually enter the dining hall. During her time in the transition unit, Mom has lost weight, so as she walks her pants begin to slither off her hips. Seeing this, Miriam reaches over to tug them up. My mother, surprised at the touch and not understanding that the gesture is intended to help, looks up and glares. Miriam backs off, and I can see that she is appraising my mother, trying to determine just what kind of patient she will be.

Satisfied that she won't be interfered with again, my mother continues lurching across the dining hall floor looking angry and scared. Sixty elderly residents glance up from their meals to watch her.

And suddenly I'm overwhelmed by that feeling you get when you send your child to the first day of school and watch them cross the schoolyard. You know that they're nervous, but you want them to be brave and demonstrate their best behaviour. You want them to be liked and accepted by the others, to find friends and build a community. Only my mother doesn't smile at anyone, and she doesn't have a neighbourhood chum to accompany her or sit at her table, and this isn't a school or summer camp that she will grow out of or ever leave. This is the final stop.

Fatigued by what for her is a long walk, she wobbles, and another attendant attempts to direct her to her table, but now Mom is anxious, and her temper flares. She snaps at the attendant to keep her hands off. I insert myself to smooth things over, but the attendant gives a quick shake of her head, indicating that it's not necessary for me to say anything, that this kind of response happens all the time. I squeeze in at the table with Mom and two other elderly residents, and talk with her while she eats. Just before I leave she asks me if Clem is going to come visit. I remind her that I am Clem, and walk away with a knot in my stomach.

Later in the evening, Liv calls and I can hear he's upset. When he visited Mom after dinner she asked if she had to stay at the Bow Valley. He answered yes, that this was where she was living now. She asked him to take her back home. He said he couldn't. She collapsed, crying, saying there was no place for her outside anymore. Liv tells me he wept at the time, and as he recounts the exchange, begins crying again.

Excerpt from The Unravelling by Clem Martini and Olivier Martini, to be published September 12, 2017 by Freehand Books.