A new exhibition at Toronto's Textile Museum of Canada tells the story of a handful of artists who created hand-printed textiles in Cape Dorset, Nunavut in the 1960s.

Canadians tend to think of Inuit art as something that adorns a gallery wall, not your living-room curtains. For a brief period in the 1960s, however, a handful of artists at Kinngait Studios in Cape Dorset, Nunavut, set out to change this with a collection of hand-printed textiles. An exhibition at the Textile Museum of Canada in Toronto tells the story of this forgotten initiative, while celebrating the new generation of Inuit textile designers who are following in its footsteps.

The story of Printed Textiles from Kinngait Studios, which runs until Aug. 30 before embarking on a nationwide tour in 2021, begins in the 1950s, as Inuit communities transitioned to a more urbanized existence in towns such Cape Dorset. With the help of artist and civil administrator James Houston, who was instrumental in establishing Inuit art as a commercial enterprise in the North, printmaking emerged as a promising means of generating much-needed income for the area.

Textile Museum exhibition celebrates an oft-overlooked strand of Inuit art history

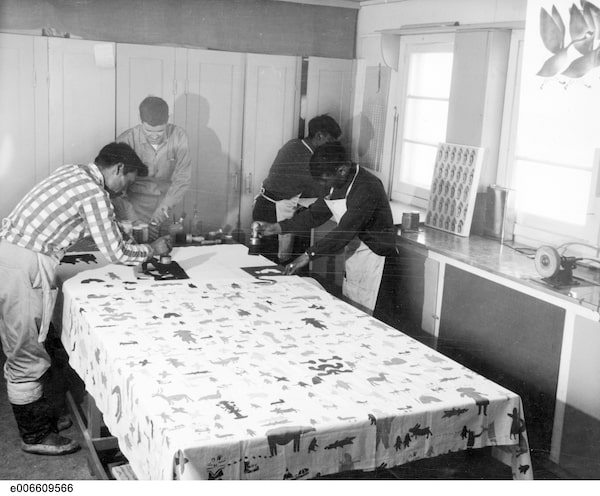

Lukta Qiatsuk and Iqaluk Pingwartok work in Kinngait Studios in this undated archival photo.

The idea to create commercial textiles, Textile Museum of Canada curator Roxane Shaughnessy says, was right on-trend. “It was a period where there was a lot of interest in elevating textile design to the status of art,” she explains, evoking Canadian graphic designer Thor Hansen, whose nature-themed prints were popular in the 1950s, and Finnish design house Marimekko, whose colourful florals were a global sensation in the 1960s. “Houston thought this was a really good idea that would sell well and provide a commercial enterprise for the artists and printers at the time.”

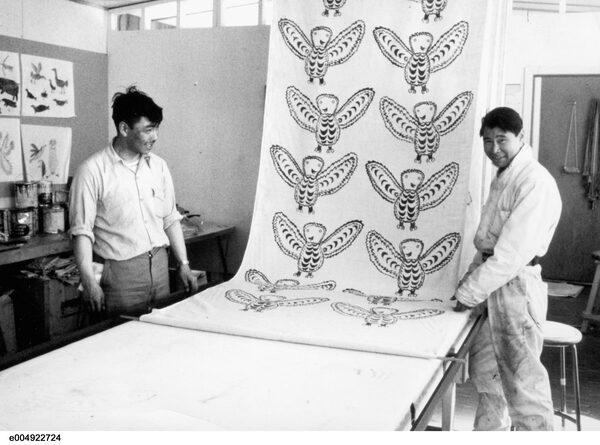

Under the supervision of Kananginak Pootoogook, who worked for years to master fabric printing techniques, the designs of artists including Kenojuak Ashevak, Pitseolak Ashoona, Parr and Pudlo Pudlat were featured in dozens of commercial textile prints at Kinngait Studios during the 1960s. The designs depicted birds, fish and parka-clad Inuit, rendered in a colourful, graphic style suited to the ebullient aesthetics of the era.

Mary Samuellie Pudlat's Fish and Shadows is one of dozens of hand-printed textiles created by Nunavut's Kinngait Studios in the 1960s. Reproduced with permission of Dorset Fine Arts.

In addition to being marketed to architects, public works officials and department stores across the country, the textiles were entered into the Design ’67 Awards competition, a program to promote Canadian design at the upcoming Expo ’67 in Montreal. The fabrics won, earning a $1,000 prize for Kinngait Studios along with a role decorating a model suite at Moshe Safdie’s Habitat ’67 apartment building.

Sadly, just as Safdie’s futuristic design failed to revolutionize urban housing, fabric printing did not prove to be a viable industry in the north. By the following year, a combination of low sales and the high cost of shipping materials to and from Cape Dorset put an end to the project. “I think it was difficult to produce, with the logistics of it all,” Shaughnessy says. “But it was remarkable how much they achieved given the circumstances."

The textiles, such as Anna Kingwatsiak's Camp Scene, seen here, render characters in a vivid, colourful style. Reproduced with permission of Dorset Fine Arts.Anna Kingwatsiak

While modern textile design in Canada’s north began with Kinngait Studios in the 1960s, it didn’t end there. Alongside the original fabrics in Printed Textiles from Kinngait Studios are new works from Martha Kyak, Tarralik Duffy and Nooks Lindell, Inuit fashion designers who are continuing the tradition of Northern textile design.

“It’s so much easier now than before,” says Kyak, who creates bold, colourful prints of Arctic flowers for her clothing brand, InukChic. Unlike her predecessors, she creates her designs digitally, has them printed onto fabric in the United States and shipped back to her. It’s less time consuming and more economical than any means available in the 1960s and, she imagines, would have made a big difference to the outcome of Kinngait Studios’ short-lived textile scheme.

“Back then, they did it by hand, and now in the internet world you can do so much more,” Kyak says. “I think they would love to see all the possibilities they could do today. I believe they would be very successful.”

Live your best. We have a daily Life & Arts newsletter, providing you with our latest stories on health, travel, food and culture. Sign up today.

Editor’s note: (Jan. 9, 2020) An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated artists designed textile prints. In fact, printmakers selected designs from artists' works to use on textiles. This version has been updated.