Denmark’s Bjarke Ingels in his New York office.

LANDON SPEERS FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Bjarke Ingels was awakened by five sparrows. Last fall, he was sleeping on a terrace at his massive new condo in Brooklyn: Having bought the place when it was listed for nearly $4-million, he'd decided to "renovate the shit out of it," he says. So he was camping outside.

This was not such a hardship. His home has a panoramic view of Manhattan, and Mr. Ingels was getting ready to put his stamp on its shore: His office is helping to shape The Dryline, a 12-kilometre stretch of green infrastructure that will protect the area from flooding.

"Since I moved to New York, I had never seen sparrows," he says with a big, seemingly earnest grin. We are in the top-floor office of his architecture firm, the Bjarke Ingels Group, whose name he chose for its acronym: BIG. "But they're here."

So is he. Mr. Ingels is a cross-over artist: an optimist who's willing to bridge the realm of high architecture – theory-driven, often hostile to commerce – and real-world development, and does so better than any of the "starchitects" a generation older than him. Most of the intellectual leaders in his field are grey-haired, and they live and speak like academics; Mr. Ingels talks about his penthouse, drives a Porsche, and uses phrases like "pimped out" in conversation. The 41-year-old, who grew up near Copenhagen, deals in American hustle; his buildings are showy but also engage with the city around them.

It's what you might call sensible starchitecture.

The Dryline: To save Manhattan from flooding, designers use urban space

3:19

This high-wire act is not without its critics, Some architects see Mr. Ingels as a servant of the rich and powerful, while others find fault in the execution of his firm's buildings, which don't achieve the precision that his competitors strive for. But his skill and influence are undeniable – and growing.

BIG, founded in 2005, now has about 300 staff, and is a magnet for young talent from around the globe. In Copenhagen, it is constructing a waste-to-energy plant that will be topped with a ski slope. The Dryline project is a link to the most important set of issues in city-building: adaptation to climate change. BIG works with a glittering array of clients: Google, Audemars Piguet watches, a National Football League team, the Smithsonian Institution, the City of New York and big, conservative developers.

Now Mr. Ingels is slated to make his mark on Canadian cities in an equally ambitious way. BIG is altering the downtowns of Vancouver and Calgary with two twisting towers: the 52-storey Vancouver House at the end of the Granville Street Bridge, and Telus Sky, which will be Calgary's third-tallest building. And this week, he will be in Toronto, revealing designs for BIG's radical condominium and retail project in the downtown core.

For any group of architects, this would be an enviable workload. For a relatively new firm, with staff whose average age is in the mid-thirties, it is unique.

Mr. Ingels's tool is the Bjarke Pitch. A book and show about the firm's work is titled Yes Is More. That's a pun on the legendary line "less is more," attributed to modernist master Mies van der Rohe. But if you don't catch the reference, it doesn't matter: Mr. Ingels wants to reach you, too, and knows how to do it.

In talks and in YouTube videos, he is relaxed and fluid. "It's a bit like cinema or literature," he tells me, lounging on a windowsill, wearing his customary uniform of jersey T-shirt, blazer and artful stubble. "The best stories are the ones that are deeply human, that somehow portray aspects of everyday life." The lights go down and he launches into a presentation of the design for the Toronto project. With his compact frame, restless eyes and top-scruff of hair, he seems, as he often does, like a lynx seeking prey. But the pitch is compelling: The logic of the architecture is surprising, and persuasive.

This sort of performance by Mr. Ingels has become familiar to observers of architecture. But the work is something else: Outside Copenhagen, there have been few opportunities to see BIG's buildings in concrete form. The firm's first major project in North America, a New York apartment complex it calls a "courtscraper," is about to get its first tenants. As BIG builds its presence in Canada and a wave of his designs move from renderings to construction – where architects' dreams often go to die – this is the year two things will become clear: whether Bjarke Ingels, brilliant salesman, is also a brilliant city– builder, and whether we are actually willing to live not just with but in new forms and types of buildings.

BIG’s new Toronto building gathers apartments into ‘peaks,’ which promise to offer an unusual intimacy between neighbours. At ground level, the design features a public courtyard.

BIG

SOCIAL CONDENSER

What if a building could bring people together? In the 1920s, radical architects in the Soviet Union designed workers' clubs and blocks of collective housing to become "social condensers," furthering the work of revolution by encouraging a collective spirit. Theatres, restaurants and libraries were brought together into cylinders and playful heaps of blocks.

Fifty years later, a new generation of theorists – most prominently Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas – started putting twists on the ideas of the 1920s avant-garde. Mr. Koolhaas imagined fanciful hybrids, buildings that took the energy of the city and expressed it within their walls. He and his partners called their firm the Office for Metropolitan Architecture.

OMA grabbed the attention of North Americans at the turn of the millennium with the Seattle Central Library – an ungainly monument that looks like a jagged stack of blocks wrapped in a glass stocking. It is organized in a radical way (the book stacks are arranged a spiral, like the stalls in a parking garage), but also flexible and capacious. One critic called it "the most important new library to be built in a generation."

Bjarke Ingels was one of its designers. He was just in his mid-twenties and yet remarkably self-possessed. Raised outside Copenhagen, he is the middle child of a dentist and an engineer, who grew up with a passionate interest in film and graphic novels. He had entered architecture school at the Royal Danish Academy of Arts in 1993 without, he has said, all that much interest in actually doing architecture.

But a few years in, he got serious. The Koolhaas book S,M,L,XL, written in 1995 with Canadian designer Bruce Mau, was on every design student's shelf. It shaped the young Ingels's design sensibility, and his rhetorical mode: "The absence of a theory of BIGNESS – what is the maximum architecture can do? – is architecture's most debilitating weakness."

He landed at OMA in 1999. It would be the only firm he would ever work for. He soon went out on his own, with Belgian architect Julien de Smedt. Their partnership – hinting at the importance of story – was called PLOT.

At 8 House, in a suburb of Copenhagen, residents and visitors can walk up a sloping path to the top level.

IWAN BAAN

MEETING THE NEIGHBOURS

In Europe, it is possible for twenty-something architects to have completed their training and to win design competitions; however, it's rare at that age to win a major commission from the private sector. Mr. Ingels and Mr. de Smedt did both. Developer Per Hopfner hired them to design an apartment building in Orestad, an unfashionable suburb on the fringe of central Copenhagen. The job didn't leave room for much creative freedom. The developer told them, as Mr. Ingels recalls it, "Make it interesting, make it attractive, and make it dirt-cheap."

Remarkably, they pulled it off. The first two buildings were called V House and M House, and each resembles its letter-form when seen from above; the third, The Mountain, stacks a layer of apartments on top of a giant mound-shaped parking garage, like a blanket on a hillside. Residents can peek diagonally over at their neighbours' terraces; it brings the intimacy of urban backyards to dwellings perched up in the air.

In 2006, Mr. Ingels split amicably with Mr. de Smedt, and built another project in Orestad under the name of BIG. Called the 8 House, it resembles a figure eight when seen from the air; where many Danish apartment buildings have courtyards in the centre, it has two. You can walk in off the street and ascend a winding path all the way up to the 10th floor; some apartments have front doors and patios on the pathway. It is a social condenser, stripped of radical politics but making life better in a bourgeois neighbourhood.

At 8 House, in in a suburb of Copenhagen, residents can walk up a sloping pathway to the front doors of their apartments. ‘The more meeting points you have with your neighbours,’ Mr. Ingels says, ‘the more you will get to know them.’

TYE STANGE

Palle Jensen, an engineer and inventor now 71, was among the first to move in. Almost every morning after breakfast, he takes an elevator to the top of the building and walks all the way down that path – "to see if there is anyone to talk to, to see if everything is okay," he says. "I see the front yards of the apartments lying close to the pathway. They are very different – and it's interesting to see how people use these spaces. There are many experiences on such a walk."

"As an architect, you can't predict that it's all going to be a success," Mr. Ingels tells me, "but you do everything you can to maximize the potential for a socially successful environment. And just as in life, different niches allow space for different life forms to settle. I think that's true in an urban environment as well. Having terraces so you can meet your neighbours; having a courtyard, an oasis. I think the more you have those things, the more meeting points you have with your neighbours, the more you will get to know them."

But Danish culture, with its strong communal bent, is especially well-suited to this fusion of public and private. How will the model of the courtyard building – where you share a space intimately with many neighbours – translate to a more individualist culture?

Via 57 West, the pyramid-like structure at left, is what Mr. Ingels calls a ‘courtscraper’; its odd geometry creates a shared space in the centre of the building.

NIC LEHOUX

COMING TO AMERICA

That is a question for which BIG will soon have an empirical answer. This month, the first tenants will sign leases at Via 57 West – BIG's first completed project in New York, an apartment building of more than 900,000 square feet. It takes the form of a hyperbolic paraboloid – more or less one-quarter of a pyramid with a courtyard scooped out of its core. It is wrapped in a skin of stainless steel, and shimmers like an enormous, benign alien spaceship on the Hudson River. Mr. Ingels calls it a "courtscraper," a fusion of courtyard building and skyscraper.

It is a brilliant piece of architecture: a very large, slightly unpolished gem.

I tour the building with Beat Schenk, a mild-mannered BIG partner and former OMA colleague of Mr. Ingels, and the firm's communications head, Daria Pahhota. As we rise in a construction elevator, the facade of the building careens away, and I feel a flutter in my gut. It is like mounting a roller-roaster – a sensation you get on very few highrise construction sites.

The inside of Via 57 West proves to be fairly unconventional: a tower with amenity rooms on the lower levels and 709 residences above. (About one-fifth will be affordable housing.) Finishes and components such as windows are tasteful but generic. Yet there are plenty of surprises: Triangular bay windows protrude from two sides of the building, providing views along the side street and avenue, while skilful tucks resolve the strange geometries that result within the living spaces.

The courtyard, designed by landscape architects Starr Whitehouse, is almost done; the brick hasn't been laid on its winding path, but the young trees are in place and, in the adjacent apartments, you can see tradespeople installing cabinets. It seems like close quarters, even by New York standards.

Mr. Schenk argues that residents will develop the manners to live here comfortably. "This place will be self-selecting," he maintains. "People who are drawn to this way of living will make it work, quite successfully, I think."

This is entirely plausible; the building is beautiful and utterly distinct. It is likely to attract a young, adventurous brand of tenant. Many urban millennials in North America – unlike their parents – use public spaces to socialize and be seen; courtyards like this one make sense in Copenhagen or Barcelona, and they will make more sense in 21st-century New York. And, perhaps, Toronto.

In any case, the odd geometry pays other dividends. Apartments on the east end of the building get to look west, over the courtyard, and enjoy river views. This is one way BIG's design solves a site that's very challenging: bordering a highway, steeply sloped, next to a power station. Plus, as Douglas Durst – the third-generation New York developer who awarded BIG the contract – recalls, Amanda Burden, the city's ambitious planning commissioner, "wanted it to be iconic. And iconic "usually means tall," he adds wryly.

C2MTL: Architect Bjarke Ingels on how failure leads to possibility

3:53

CRAFT, COMMUNITY AND COMPROMISE

The fact that Mr. Ingels and his team embraced the developer's requirements is entirely typical of BIG – and not always of other high-design architects, whose work is driven by a less pragmatic and more sculptural ethos. This, to Mr. Durst, is part of what makes Mr. Ingels so special. "Bjarke comes up with innovative solutions, but they're solutions based on the site," he says. "Also, he doesn't invest himself in a design. When he designs something, he is very aware of how to build it. And sometimes that has to change."

This eagerness to work with clients' agendas – together with the easy, one-line quality of many of his narratives – has made Mr. Ingels a target for criticism from within the architecture world. As an alumnus of OMA in Rotterdam, he is connected to many of the intellectual leaders of the profession in Europe and North America, both in the academy and in so-called "design firms." These are smart people who are accustomed to having their wisdom largely overlooked by the marketplace; they share progressive politics, a deep concern for sustainability and a fraught relationship with money.

Their culture does not know quite what to make of Mr. Ingels and his post-ideological approach to his clients. He has been a collaborator with Fox News, various sheikhs and, recently, an NFL team. (BIG won't say which one, but Mr. Ingels hints that it's the Washington Redskins on his Instagram feed.)

Mason White, an architecture professor at the University of Toronto and principal of Lateral Office who moves in the same intellectual circles as Mr. Ingels, praises BIG's work as "intelligent and carefully crafted," but he questions the lack of a social agenda. "Bjarke has certainly mastered the art of cool and the art of presenting the architect," Prof. White says. "I don't know whether there are larger aims than coolness and accessibility."

And this is just as the architecture world is increasingly putting its emphasis on social justice. This year the Pritzker prize – architecture's most prestigious award – went to the Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, whose work includes formally inventive high-design structures but also highly flexible schemes for social housing.

"In a year when someone like Aravena is winning architecture's most coveted prize," Prof. White says, "that may be the only thing [Ingels is] missing: any understanding of a bigger social intent."

Mr. Ingels argues that designing corporate office towers and football stadiums to be more urbane is a way of making real change. "Each time we have a chance to design a building, or flood protection or whatever," he says, "we try to do it in a way that moves the world a little closer to what we would wish it was."

Others in the profession are less kind. Kyle May, a New York architect and editor of a journal, CLOG, says BIG is no heir to the critical tradition of Rem Koolhaas; he compares it, instead, to corporate architecture firms that value competence over progressive politics. Their work, he says, "is superficially playful … The singular gestures do not have any social value, as far as I can see."

In 2011, CLOG devoted a special issue to BIG. Then, Mr. May noted a sloppiness about its actual buildings. "When translated into built form, the work to date lacks the understanding that a 'master builder' or 'master craftsman' would employ," he wrote. "With an emphasis on getting the diagram built, the craft and longevity of the work is abandoned."

I put the latter idea – that BIG doesn't focus on small details – to Mr. Schenk, and he half-agrees. (This point is brought home on our tour when we almost get lost in a parking garage.) That's inevitable, he argues, when you are designing something enormous: "In a 900,000-square-foot building, there are compromises," he argues, and concedes – raising his voice over the whine of a table saw – that BIG chooses its battles. "If two panels don't line up, it doesn't destroy everything."

In the world of architecture, that is a real question: How much does precision matter? Mr. Schenk mentions Italian architect Renzo Piano, whose own recent New York building, for the Whitney Museum, is built with almost ludicrous exactitude. But his point applies equally to many of the world's elite architects. Whatever the specifics of the design language, their art demands the exact resolution of details; that, as Mr. Schenk suggests, panels on a facade or wall must meet in a specific manner and rhythm, creating a subtle compositional order that elevates space into art. This is one way that architecture, at its highest level, works.

The danger is one of emphasis. When architects are too busy at this level of refinement, they can go into navel-gazing mode, solving problems that are invisible to almost everyone else. Too often, the result is that thoughtful architecture is seen as a luxury – important to art museums and rich people's houses, irrelevant everywhere else.

Mr. Ingels himself has nothing against this sort of bespoke work; he speaks wistfully about the pristine minimalism of the Japanese firm SANAA. Yet BIG plays a different game: Its mode of working is squarely focused on bigness – in scale, in number of projects, in cultural reach. Mr. Ingels calls himself a "pragmatic utopian," and emphasizes that theme.

"For me, you need to know why you're doing what you're doing and why it matters," he says. "You need to have an agenda. But if you have a lot of theoretical ideas that are divorced from the reality you're part of, you will effect zero change."

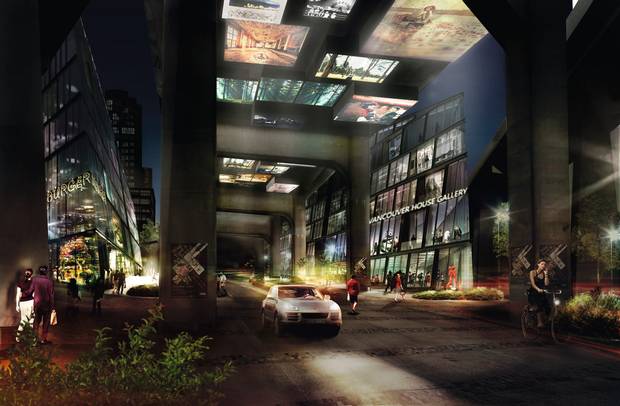

Along with a dramatic tower, BIG’s Vancouver House development will include a varied zone of public space, retail and offices that will bring life to the area under a bridge and off-ramps.

BIG

BUILDING FROM THE GROUND UP

For today's city-builders, the name "Copenhagen" captures a whole set of civic virtues: The city's low-but-dense apartment blocks, consistent and highly walkable streets, and urban planning that places the emphasis on bikes and pedestrianism.

This encourages a no-nonsense approach to designing buildings and blocks. World-renowned local planner and architect Jan Gehl writes about "the city at eye level." There should be a consistent "street wall," lined with shops and restaurants that supply a mixture of experience and things to do.

That has put Mr. Ingels in an awkward position: his bold forms have sometimes failed to play nicely with the streets and buildings around them.

When Brent Toderian, the prominent Canadian urbanist, visited Copenhagen in 2007, he went to Orestad to see the VM Houses. He was not impressed to find them surrounded by lifeless storefronts, fences and empty sidewalks.

"I gave a talk at the Danish Architecture Foundation," he recalls, "and I made the joke that I was a fan of this hot young architect, Mr. Ingels, from the second floor up, but he didn't know how to land a building.

"The word got back to Bjarke, and the next morning, we had breakfast."

The two bonded over a shared love of comics. But Mr. Toderian, who was then Vancouver's chief planner, had some words of caution: "I told him I would be happy to bring him to Vancouver – but not yet. I was looking for evidence that he wasn't just showboating, that he could under– stand the fundamentals of smart city-making."

To his eyes, the intellectual tradition that produced Mr. Ingels's buildings is fundamentally about "a rejection of the city," he says, "or a rejection of the street." Building large, complex, self-contained buildings made some sense when the streets are filled with perceived threats – as in 1970s New York – or when you are working in a city centre that was utterly levelled by the Second World War, as was Mr. Koolhaas's home base of Rotterdam.

It's different in contemporary Vancouver, and in Copenhagen, where a dense, walkable, transit-oriented downtown serves the linked goals of sustainability and a rich social and cultural life.

Mr. Toderian suggests that Mr. Ingels, as a student of Rotterdam's self-containment but a native of Copenhagen's open streets, had to mature in order to assume the birthright of his home city. "He has urbanism in his DNA." Still, in Mr. Toderian's telling, it took a nudge.

Three years later, he connected Mr. Ingels with one of Canada's most ambitious developers: Ian Gillespie of Vancouver's Westbank Projects. "Right away, you get drawn in by this incredible intellect," Mr. Gillespie says of Mr. Ingels. "Within 30 minutes of meeting him, I said, 'I'll get you a project within the next 30 days.' " And Mr. Toderian had a site in mind for a rare, landmark building: a series of lots at the foot of the Granville Street Bridge which were partially owned by Westbank. A development would have to make something of the dead zone of body shops and parking lots underneath the bridge and off-ramp – and find room for a tower, while keeping the apartments at least 30 metres away from the bridge itself.

Mr. Ingels and BIG partner Thomas Christofferson solved the problem, as the former recalls, within an hour. The result: a skinny tower, just 6,000 square feet at its base, that pivots and expands as it rises, leaning into the airspace above the bridge. "It was incredibly elegant," Mr. Gillespie says. "And it wasn't bringing an architect with an ego to build a sexy building. The shape of the building came, to an inch, from the constraints of the site."

Dubbed Vancouver House, the result is a twist on the Vancouverism model of urban design: a skinny tower full of people on a broad base that fills in the street, adapted for a ragged corner of the city. "This is," Mr. Toderian says, "Vancouverism 2.0." The plans include a lively, pedestrian-friendly zone under the bridge and ramps, including a major public-art project by Rodney Graham, flanked by offices and retail space and a network of courtyards. It is, in other words, just as important for the way it shapes the street as for the way it sculpts the skyline. Getting it right has required the active participation of not just BIG, but the developers and the city.

A model suggests the ‘pixellated’ geometry of BIG’s Toronto project.

LANDON SPEERS for the globe and mail

PUTTING THEORY INTO ACTION

That same recipe will be required in Toronto, when Westbank, partners Allied REIT and Mr. Ingels try a similarly complex piece of urban surgery.

So far the partners have designed creative highrises, with Vancouver House and with Calgary's Telus Sky. But with their attention to a broader notion of city-building, as at Vancouver House, they promise to add some richness of experience to the city and, perhaps, make serious architecture relevant to the broader culture.

This, says Mr. Gillespie, is why he values working with BIG. "We bring them projects where that's the lens: Where do cities need to get to to solve the problems that we have as a society? That's what I find interesting about Bjarke and BIG. They're not just building a nice-looking building – they're trying to advance the cause."

Is that cause a more humane city, a more interesting skyline or healthy profits? Mr. Ingels's entire career so far has been a drive toward an answer to that question: All of the above. Yes is more. BIG's architecture – loud, iconoclastic and often brilliant – will show us just how far the contemporary city is ready to stretch.

Alex Bozikovic is The Globe and Mail's architecture critic.