Architects may not solve the world’s biggest problems – but it’s their job to try. That is the message that the Pritzker Prize sent this week when it honoured the Chilean Alejandro Aravena with the profession’s most prestigious award.

The Hyatt Foundation announced Wednesday that Aravena had won the $100,000 (U.S.) prize. Often called architecture’s Nobel, it has previously gone to many of the world’s leading figures of high design, among them Frank Gehry, Renzo Piano and Zaha Hadid.

Compared with those so-called “starchitects,” and their principally aesthetic set of concerns, Aravena couldn’t be geographically or conceptually farther away: He is young, at 48; and almost all of his projects are in his native Chile. And, he is best-known for scrappy but effective social-housing projects, in which he leaves room for residents to invest their own work and resources to alter his designs.

His win reflects a new set of values that the Pritzker began to signal with its 2014 choice of the architect Shigeru Ban – that architecture bears a responsibility to the global 99 per cent and architects must address rapid urbanization, which will see two billion more people heading to cities by 2030.

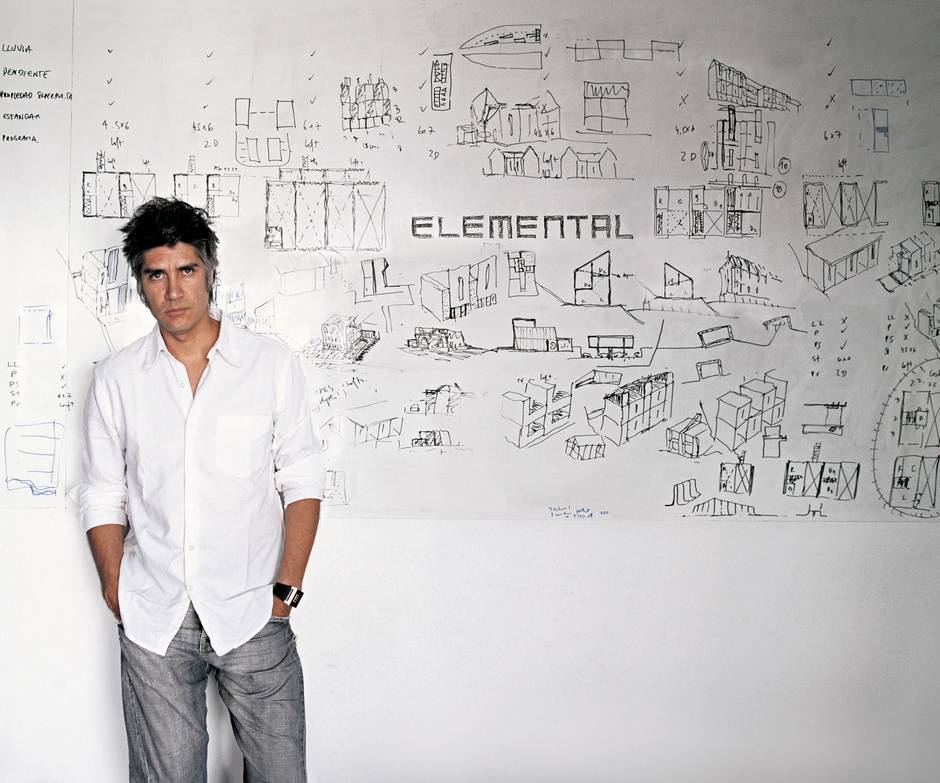

Speaking on the phone this week, Aravena sounded dazed by the news of the prize. “I really didn’t see it coming at all,” he said from the office of Elemental, his firm in Santiago. (This despite the fact he sat on the jury of the Pritzker Prize from 2009 to 2014.)

But he is excited, Aravena said, to use the “gravitas” of the prize to change the conversation. “We’re witnessing new challenges and problems in the built environment. The questions are new, and the starting points are very far from architecture.”

That is, he said, “the forces at play in cities, from migration to insecurity to pollution to inequality. These are problems that do not belong to the architectural realm. They are issues that interest society at large.”

For architects, Aravena told me, “the challenge is: How do we use our specific expertise and translate these issues into form?”

Elemental, he said, calls itself a “do tank” – riffing on the idea of a think tank – and specializes in social housing. The firm has built more than 2,500 units, in which the key idea is participatory design: design, that is built on deep and meaningful consultation with social-housing residents about how they want to live.

The most powerful project is one it dubs “Half of a Good House.” Asked to design social housing for the Chilean city of Iquique, the firm determined that the available government subsidy – just $7,500 (U.S.) per unit – would provide either a too-small unit or a site on the outskirts of town, “segregating people from opportunity,” Aravena said. (“The city,” as he and his partner Andres Iacobelli wrote in their 2013 book Elemental, “is a shortcut toward equality.”)

How to resolve the problem? Pick a central site, and give each family half of a middle-class house, with room to build the rest themselves and, in so doing, build wealth.

Iquique was home to the first such project, called Quinta Monroy. The result was a string of three-storey duplexes; one deep unit on the ground floor, and a tall one on the second and third floors. But the buildings are separated by side-yard spaces of equal size – with a second-floor terrace – so that each family has the opportunity to build out the missing half of their house, on the ground or on the terrace above. “That way,” Aravena said, “you channel the capacity of the families themselves to provide housing – and create opportunities.”

It’s an elegant scheme, designed to work around the specific capacities and needs of the community and society. And, importantly, it works, and has been reproduced on more than a dozen other sites in Chile and elsewhere in South America.

Aravena argues that large-scale problem-solving is what architecture should be doing now. “In social housing, there is no time for what’s not strictly necessary,” he said. “There is no arbitrariness.”

It’s hard not to read this as a critique of other architects who have won the Pritzker in the past – the digitally designed, self-consciously swoopy buildings of Hadid, for instance, definitely include a degree of arbitrariness.

But Aravena won’t be drawn into a war of words. “We look very little at what other architects do,” he said. “Our problems are so tough … we’re trying to be really rigorous.”

If there is a war of ideas in architecture, then Aravena is clearly winning. Along with serving on the Pritzker jury, he has taught at Harvard’s world-leading Graduate School of Design, and will direct this summer’s Venice Architecture Biennale, the architecture world’s most important festival of ideas.

He is articulate in English and telegenic; his TED Talk about his practice has been viewed more than a million times.

And yet Santiago is a long way from the design world’s centres of power. Most of the Pritzker winners have been American or European, with a handful from Japan and one from China. Aravena is the fourth Latin American winner since it began in 1979. And the postwar architecture of Latin America – with the exception of Brazil – remains relatively obscure; in fact, a show last year at New York’s Museum of Modern Art was greeted as a revelation.

Chile is something of an exception. The country of just 17 million has dozens of architecture schools, and punches far above its weight in design terms. Aravena feels that the country and its thinkers benefit from their position “between the First and Third World,” he said. “Because we’re relatively poor, the constraints act as a filter to the arbitrariness. You need to justify why you’re doing what you’re doing, but we’re not that poor that we’re in survival mode.”

To Aravena, architecture demands financial and technical expertise: His business partners in Elemental include Iacobelli, a transportation engineer whom he met while teaching at Harvard; and the company is co-owned by a major Chilean energy company, COPEC, and the Catholic University of Chile in Santiago. That’s an unusual arrangement, and it reflects Aravena’s focus on getting things done.

Aravena and his firm are engaged with all of the most urgent themes in contemporary architecture. Along with social housing, they think about the city and climate change; they have designed a riverfront park in an oceanfront city that serves as a buffer for flooding. And they think about the environmental impact of their buildings, which strive to suit the local climate and, in so doing, become more efficient. A string of buildings at the Catholic University in Santiago show finesse in that respect: the Anacleto Angelini Innovation Centre, completed in 2014, places the complex research institution behind a thick concrete skin, which moderates the effects of the local desert climate.

Elemental’s upscale work is strong but does not warrant the Pritzker on its own; in our interview, Aravena said as much. But he also argued that high-end projects, such as an office complex Elemental is designing for Novartis in China, can inform humanitarian work. “The way to train our design muscles,” he told me, “is in high-end buildings where careful design is at its highest.”

Artful architecture, then, is not dead; it just needs to find the right purpose. “We are not concentrating on the handwriting,” he said. “We concentrate on what we are saying with our writing.”