Ever since architectural modernism hit its stride a century ago, designers have been dreaming up houses of the world to come, and occasionally seeing them actually constructed.

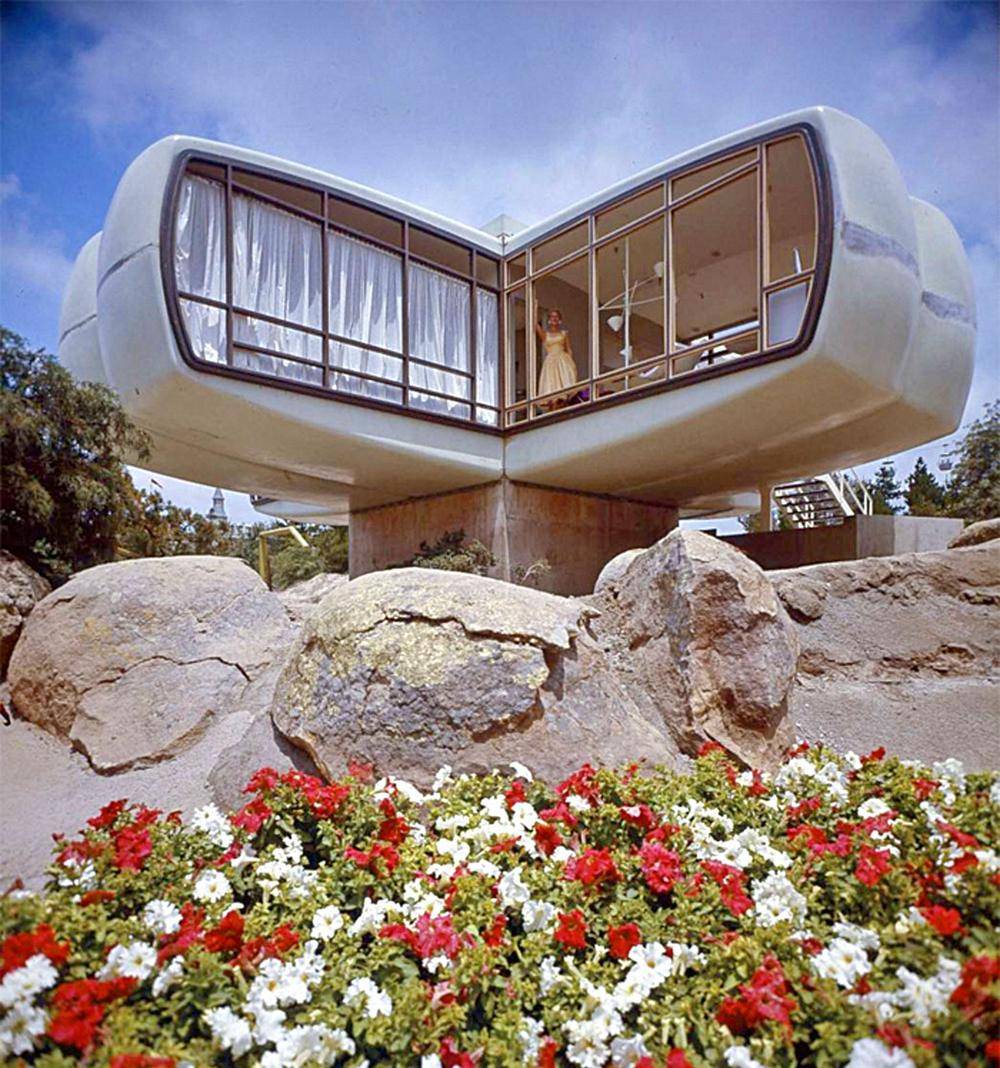

Some of these experimental essays in futurity have been hailed as forerunners of now-common technologies, styles and systems. Philip Johnson’s steel-framed Glass House (1949), in Connecticut, for example, is an ancestor of every transparent contemporary home. The judgment of history has been less kind to others, such as the House of Tomorrow at the 1933 world’s fair in Chicago. This building featured a hangar for the personal airplane that the architect believed every American family would have in years to come. But while it quickly became obsolete, the project was thrilling for its visitors at the time.

The same probably can’t be said for Disneyland’s Innoventions Dream Home. Though open to the theme-park public for only six years, this “house of tomorrow,” decorated like a ranch-style from the 1970s and outfitted with gizmos supplied by Microsoft Corp. and Hewlett-Packard, already seems dated.

That said, Disney’s Dream Home does one thing that every self-respecting house of tomorrow does: It showcases inventions (in this case, digital ones) that promise to reconfigure our relationships with the world and each other, or are already doing so. But if Dream Home were on top of its futuristic game, the place would also offer visitors experiences with new materials, radical furnishings. It would celebrate new spatial strategies that reflect the changed character of the North American family, new ways of negotiating our life-practices within the framework of legal and environmental limits. It would be about everything “smart,” not just phones and screens.

Designing a house that embodies smartness, in all its contemporary dimensions, is a stiff challenge. But it’s one that some enterprising Ontario undergraduates and graduate students in architecture, engineering and environmental design programs will likely accept and run with as contestants in an interesting and potentially exciting race recently announced by WORKshop, Inc., the Toronto design centre (80 Bloor St. W).

Organized by Larry Richards, creative director of WORKshop and former dean of the University of Toronto’s architecture school, House 2020, described as a “competition for a smart house of the future,” is a province-wide search (according to a statement) for housing “ideas that are realizable, pragmatic, and cost-effective.” Students who decide to take part “are encouraged to think openly and broadly about a smart house and changing life styles. For example, there is no fixed notion of family, number of occupants, or number of units on the site.”

What is meant by “smartness” is left open for interpretation. It may signify specific topics, such as “innovative land use planning and the creation of a community,” the “intelligent use of resources,” “technological innovation, efficiency, and convenience” – or all of the above.

By the deadline for the first juried winnowing of applications – Aug. 22 – participants will have produced schemes for one or more buildings totalling between 2,500 and 4,000 square feet in area, to be set down “on a flat suburban site in Southern Ontario.” This site will be an oblong “with similar lots continuing on either side” – a typical patch of suburbia, in other words. The first three contestants past the post in the initial vetting will be matched with technical consultants. The experts will then help the finalists prepare their proposals for the second and final round. Prizes totalling $3,700 will have been distributed by the time the competition is over, in late fall.

With any luck, House 2020 will summon forth a basketful of intelligent, well-informed, perhaps even visionary designs for homes of tomorrow – or, at least, of tomorrow’s suburbs. Students likely to pitch their ideas are up to speed already with the newest technologies, techniques and materials – so we can expect, if not airplanes in the driveways, then proposals that are at the leading edge of our cultural moment, and maybe even beyond it.

At the practical level, participation could lead – just possibly – to a significant career opportunity. In an interview last week, Mr. Richards underscored the point that contestants should think of their projects as doable “prototypes,” not blue-sky fantasies. The reason: House 2020 is the brain-child of Kin Yeung, the Hong Kong-based developer and luxury-brand entrepreneur, and the financial backer of both WORKshop and the contest. Mr. Yeung’s family has undeveloped property near Toronto, Mr. Richards said, and the businessman is keen to put smart housing on the land. He has been thinking about smartness for a long time, and he has been looking for ideas.

While this backstory probably should have been made plain in the brief, the inspiration that has resulted in House 2020 is good and sound. A juried competition is surely the fairest, most sensible mechanism in existence for digging up fresh architectural “ideas that are realizable, pragmatic, and cost-effective” – and as smart about tomorrow as we can hope to be today.