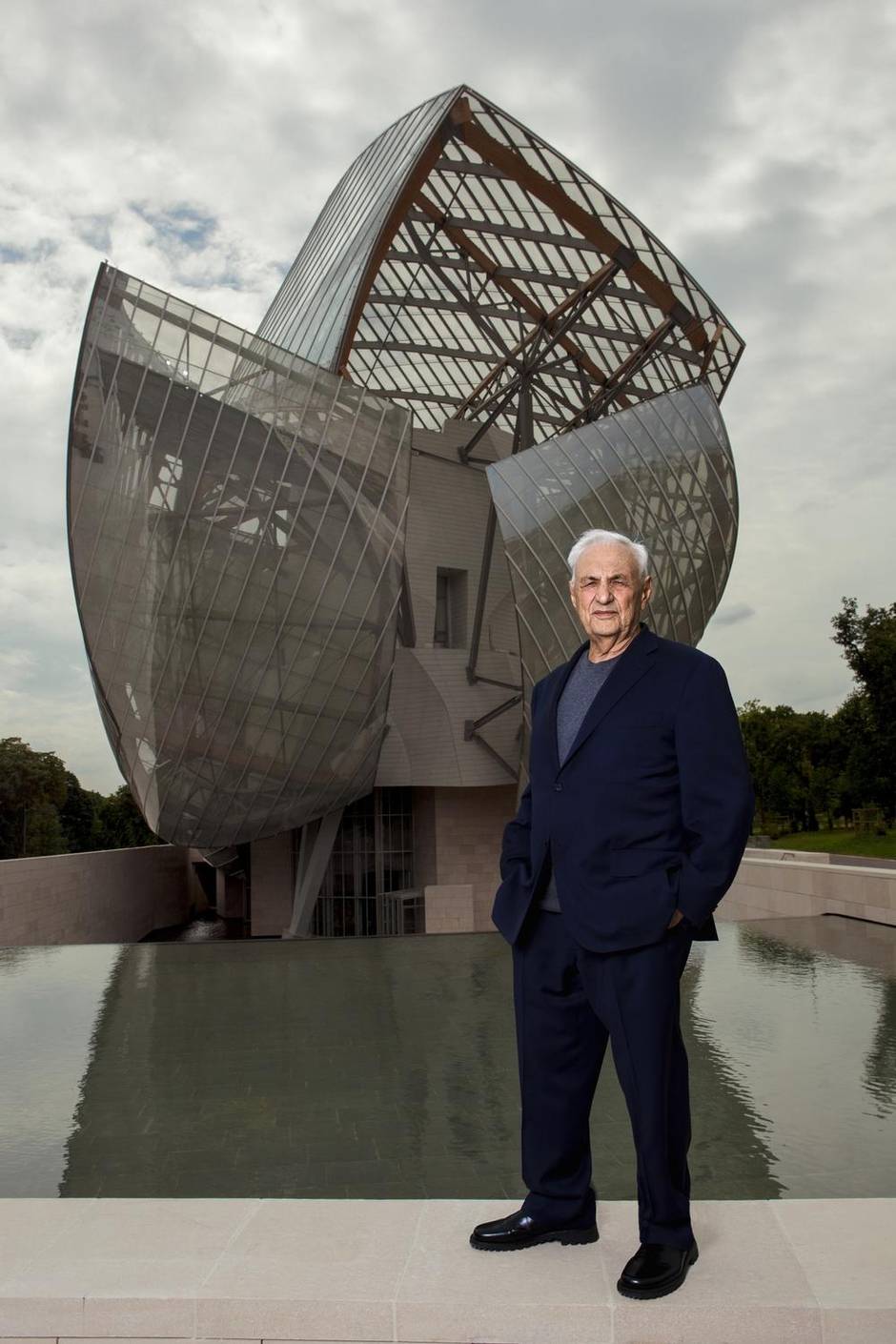

Frank Gehry was in Paris, and he was holding court. He’d just finished a day of press to unveil his new museum, the Fondation Louis Vuitton, and he was in a celebratory mood. As we sat in the café of a luxury hotel off the Champs-Elysées, friends and admirers – and Pharrell Williams – lingered to shake hands and congratulate him on the building, which is opening to critical praise and warm words from the French establishment. “You’ve got a real winner there,” said an old friend.

“Maybe,” said Gehry. “Maybe.”

Is he really so unsure? At 85, he is unquestionably the leading architect in the world, and the new museum is being hailed by its billionaire patron as a “masterpiece.” And yet. “I’m so fucking insecure,” Gehry told me. “Still. I call it a healthy insecurity; it keeps me going.”

This is a familiar tension for the man who was born Ephraim Owen Goldberg in Toronto, grew up poor and only began chasing his creative ideals in middle age. In the 17 years since his Guggenheim Museum Bilbao put a radical twist on contemporary architecture – and made him improbably famous – he has mellowed very little.

The character of his work has changed, however. His designs once tended toward industrial materials and raw edges; the Vuitton museum is a late-career work that shows Parisian decorum. It brings many of Gehry’s ideas together into a composition that is challenging but also, without a doubt, beautiful. It is also controversial. The 126,000-square-foot building is a private museum and auditorium that sits improbably on public ground, the Bois de Boulogne in western Paris. It was commissioned by Bernard Arnault, the head of the luxury-goods conglomerate LVMH, largely to show the company’s and his own considerable art collections.

The building speaks directly to the tradition of glass pavilions, including the Grand Palais in central Paris; yet getting it approved was a long and contentious process, ultimately requiring a push from France’s National Assembly.

The Fondation building, whose gestation began over a decade ago, feels a bit like a time capsule from the Age of the Starchitect. Beginning in the late nineties, many institutions chased after Gehry-like museums that, they hope, will replicate “the Bilbao effect” and transform their cities. Many of those pursuits failed institutionally and aesthetically, and over the past half-decade many architects have aspired to more socially engaged work. Gehry’s success helped elevate architecture to a prominent place in the culture – and created a school of star designers whose work most often serves the whims and the interests of wealthy patrons.

Gehry’s Paris museum does just that, but on those terms it is a spectacular success. Arnault was inspired by the example of Bilbao, and his museum, richly funded and well-situated, is a showpiece that also makes a strong argument for Gehry’s continuing creative power.

You first see it as a glassy, slightly indeterminate form among the trees. This is the museum’s wrapper, a set of curvaceous glass forms that Gehry likens to a set of sails. The glass façades are a fairly new choice for Gehry; he used one to remarkable effect at the IAC headquarters in New York, and he is testing glass systems for the towers of the massive Mirvish Gehry condo project in Toronto.

Like the titanium outer layers that sheathe the Bilbao museum and Disney Hall in Los Angeles, the Vuitton’s envelope surrounds and partially obscures the structure within.

But it also produces contradictions. Gehry’s designs have often been labelled as “object buildings,” but this one’s edges are indistinct. Where does the building end? As you linger on one of its rooftop terraces, sheltered by the sails but looking out over the city, are you within the building or outside it? Here you can touch the smooth outer walls of the museum building, made from custom panels of fibre-reinforced concrete, and also see the heavy structure that supports the great sails. Up close, the sails feel more like infrastructure: They sit on massive frames, and brawny trusses of steel and of glue-laminated larch collide at unlikely angles before your eyes.

Down below, the building consists of three irregular stacks of galleries, one of them with an auditorium space at the bottom. A glassed-in lobby at the centre brings you in at the bottom of the middle stack; from here you move up and down through a complex split-level plan. The museum’s bulk goes down into the ground; it is surrounded at one end by a long, stepped waterfall and a sunken reflecting pool, lined with limestone, that reads as a very lovely moat. (The Bilbao museum has a similar one, at ground level.) The routes between include an elevator, an escalator and several staircases; one surrounded by a curtain of glass, and another by steel walls and columns that fold like origami. At times the museum feels like the world’s loveliest construction site.

Sculpture and architecture, finished and unfinished, polished and rough; The building expresses several of Gehry’s long-standing preoccupations. “You can’t escape yourself,” he told me. “It’s human nature not to escape your signature, your language. I wish I could. I try and don’t always succeed. But think the work looks different enough in the end.” He aims to make it new, just as he has since the 1960s. Back then, the challenge for ambitious architects was how to disrupt the High Modernist language of the pristine box and move the art forward. Some of Gehry’s peers turned to quoting historic forms – pediments and colonnades in concrete. This proved a dead end.

Gehry, immersed in Los Angeles, developed an architecture inspired by the ad hoc cityscape he saw around him: warehouses, oil wells, cheaply built stucco boxes. “All around me they were building tract houses, and hammer marks were part of the game,” he recalled during our conversation. “And artist friends were making paintings with trash” – Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns – “and I went with that.” This preoccupation with the rough and the castoff became an important theme for his crowd of L.A. architects, including Thom Mayne.

Gehry became “the cheapo architect,” as he called himself, beginning with small experiments. There was a home and studio for the artist Ron Davis, a deceptively simple wedge whose irregular shape produced a trick of perspective and which was clad in industrial corrugated steel. Then in the late seventies, Gehry attacked his own family home in Santa Monica. He took a standard suburban house and wrapped it in a sculptural assemblage of chain-link fence, two-by-fours and galvanized zinc. Inside, he pulled open walls and ceilings to reveal their wood framing.

Gehry, who until the 1970s had been designing sober buildings for corporate clients, blew up his business model and began to pursue his own aesthetic more freely. He has never been a theorist, and he had an uneasy kinship with the deconstructivist movement (which produced, among others, Daniel Libeskind). Instead he proceeded to follow his muse, working intuitively and individually.

Over time he explored a series of other motifs and ideas, which are catalogued well (if superficially) by a major retrospective of his career at the Pompidou Centre that opened this month. He became a critical favourite by the 1980s as he continued to explore new motifs. There was the building as a village of individual rooms; the self-conscious use of familiar shapes, including a fish and a boat, in various media; and finally complex shapes that edged toward a private, idiosyncratic language of pure form.

At the Vitra Design Museum in Switzerland (1989), Gehry achieved a museum building that seemed to be literally coming apart – curves and shards that somehow contained a coherent interior. This effect was achieved using drawings on paper and conventional fabrication, but it soon became clear that more advanced tools were needed. By 1990 his office was working with CATIA, 3-D design software developed for the French aerospace industry; it allowed them to conceive complex shapes in tremendous detail, and ultimately to communicate these ideas clearly to builders.

The payoff came in Bilbao. The museum there, designed for the Guggenheim Foundation, was the first building that showed the true creative potential of digital design: Its wild exterior forms would’ve been impossible otherwise. The building was also sacrilegious in its approach to art galleries: Its split-level layout included nine galleries of irregular shapes and proportions.

That is true of the Vuitton museum as well. Its 11 galleries include a few large, rectangular volumes; others are smaller and idiosyncratic, topped by vertiginously high ceilings or deep, twisting skylights. They are joined together by a range of atriums and stairs, mostly glassed in and carved into unusual shapes.

For LVMH’s widely varied collection of contemporary art, the museum should work well, though it does not generally provide the neutral spaces that remain preferred by most curators. “I think the folklore on what a gallery should be, to be real, is folklore, and it ain’t necessarily so,” Gehry told me. “I’ve always talked to artists, and all my artist friends love Bilbao, and all the museum curators and directors hated it.” A few works in the new museum’s opening show were specifically commissioned, including an installation by Olafur Eliasson of triangular columns – mirrored and lit with yellow – which sits alongside the below-ground reflecting pool. They work beautifully. A set of paintings by Ellsworth Kelly, which consist of coloured squares rotated a few degrees off pale, square bases, reflect the tension between pure form and disorder that infuses Gehry’s work: As some drawings in the Pompidou show reveal, he has often developed his irregular forms by taking a shape such as a square and twisting it a bit. Within disorder, there is order.

It’s not the order you find in Paris’s neo-classical and Beaux-Arts buildings, which Gehry first saw in person when he worked here briefly in 1960, but there is order all the same. Gehry often thinks of precedents from the history of art and architecture, as well as his creative contemporaries: Baroque architect Borromini and the late U.S. artist Gordon Matta-Clark, who made fragments of demolished buildings into compelling sculpture, are both in his head.

But you don’t have to think in terms of art to enjoy (or dislike) Gehry’s buildings. His work is always open to interpretation and metaphor. The Bilbao building can look like an artichoke or a dress billowing in the wind – the New York Times critic Herbert Muschamp cast it, memorably, as “the reincarnation of Marilyn Monroe.” Gehry thinks in metaphors himself and doesn’t mind if you do; he nicknamed an office building in Prague “Fred and Ginger,” and you can easily see the couple leaning in.

This sets him apart from many of his peers. Today’s architectural good taste holds that similes can be implied but never quite stated. So why the sails, and the fish-shaped lamps in the café of the museum? “What’s the alternative?” Gehry replies. “Forms that are strange, like Zaha [Hadid’s]. I don’t know. I’m not convinced.” Borrowing forms is what artists do, he suggests, and have always done. Gehry cited something he’d seen a few days before at the Pompidou’s Duchamp show, a Léger abstraction that borrows its forms from Duchamp’s groundbreaking Nude Descending a Staircase. “It’s amazing,” he said. “Everybody’s talking to everybody.”

The Vuitton also has an open-ended quality. It is a ship, or a whale, or a box surrounded by sails, or as one Parisian put it to me, a butterfly about to take off. Choose your interpretation. Likewise, it has many moments that feel unfinished – the expressive heavy engineering of the sail structure, for instance, and a tall staircase that’s enclosed with beams of cheap corrugated steel. For Gehry, these details make the building friendlier and more humane. “I like the unfinished,” he says, “because it’s living. It’s not there yet. You can add to it yourself.”

In fact, though, you can’t, unless you work for Bernard Arnault. The museum is a private institution – it bears the Louis Vuitton logo on its façade – and its presence on public ground has been hotly contested in France. While the site is leased and will be transferred to the city after 55 years, it remains the province of a highly profitable company.

In this sense it’s an extension of a historic type, the private collection open to the public. Today’s 1 per cent have taken that model to a new and more ostentatious level, including in America – Gehry’s hometown will get a major new museum next year to house the collection of billionaire Eli Broad. The Fondation Louis Vuitton museum is aimed at the sensibilities of LVMH’s high-net-worth customers. By housing art from the corporate collection and hosting high-profile cultural events, it will lend the aura of art to the LVMH brand, something that is increasingly crucial as luxury consumers seek intangible qualities in the brands they buy; and by showing off Arnault’s own work, it will render that work more visible and hence more valuable. Meanwhile, Gehry’s office has designed shop windows for Louis Vuitton.

Does this bother Gehry? It does not. “Here’s what I think: When I started in architecture, I always looked at fashion magazines,” he says affably. “I always paid attention to fashion.” And, he adds later, architecture has always had patrons.

Success in the practical sense remains important to Gehry, whose complex projects make for a challenging business model. He also clearly feels that the contradictions and challenges of architecture in 2014 are not his to solve. He has few acolytes, and has never shown an interest in finding them. Instead he works. When we spoke, he was planning to fly to Bali this week to look at a new commission. Why? “They called me!” he said with a laugh. “And they’re paying for the trip.” It was reason enough – the chance to keep exploring, finding new forms, and in the search perhaps to find himself a bit at peace.

Meanwhile, the Vuitton museum is a late masterwork, which is settling in to its context. In the Métro nearby, I saw a sign where an illustrator had drawn a simplified version of the museum. It didn’t really look like the building at all, but it was a sign all the same that this work of architecture – singular, irreducible – was already becoming part of the Parisian landscape, even as its architect keeps moving.