Darting along the Thames on a river bus called the Clipper, photographer Lucinda Grange is explaining her fascination with bridges. “They make a city what it is,” she says, pointing east toward the familiar turrets of Tower Bridge, which turns 120 this year. She goes on to rank her favourite British cities by the magnificence of their bridges. “Newcastle has the Tyne Bridge, which represents the city on the Newcastle Ale bottles. And the Forth Road Bridge in Edinburgh – it’s visually stunning.”

Often, she notes, they have a value that emerges over time. “Bridges are also a way of making sense of a city. Take Venice – it can seem like a labyrinth, but on a bridge, you can gain perspective.”

We pass under the concrete manifestation of London Bridge, site of the Thames’ first, wood crossing, which appeared around 55 AD. For a fleeting moment there is no light – just the dank, dripping concrete blocks and the vestiges of high tide on the pillars.

The contrast between the vibrant, congested thoroughfare above us and this cold, decaying mass is profound. Grange plays it up. “London Bridge appears modest now, but its history is vast. In the 17th century, it was one of the most crowded places in London, where the Bubonic plague festered. Jack the Ripper was thought to have crossed it. In the 1300s, they would display the severed heads of traitors, so you would see them as you passed beneath.”

Grange is a self-described adventure photographer, who scales up urban monoliths to get the most splendid angles for her art. Her groundbreaking photo of London Bridge’s interior shell – like the inside of a spacecraft rendered in concrete, taken earlier this year while dangling above the tide from the belly of the beast – is a highlight at the Museum of London Docklands’ latest exhibition. Bridge chronicles the landscape spanning the Thames and considers the social, architectural, economic, even emotional impact of bridges in the British capital.

“Bridges are a great motivator,” says Francis Marshall, senior curator at the museum. “London’s bridges give a view of the capital impossible to appreciate from its jumbled medieval street plan. Most of the time we are in a maze of streets and the city reveals itself in fragments. On a bridge, however, the full panorama is laid out … and you understand the significance of being here.”

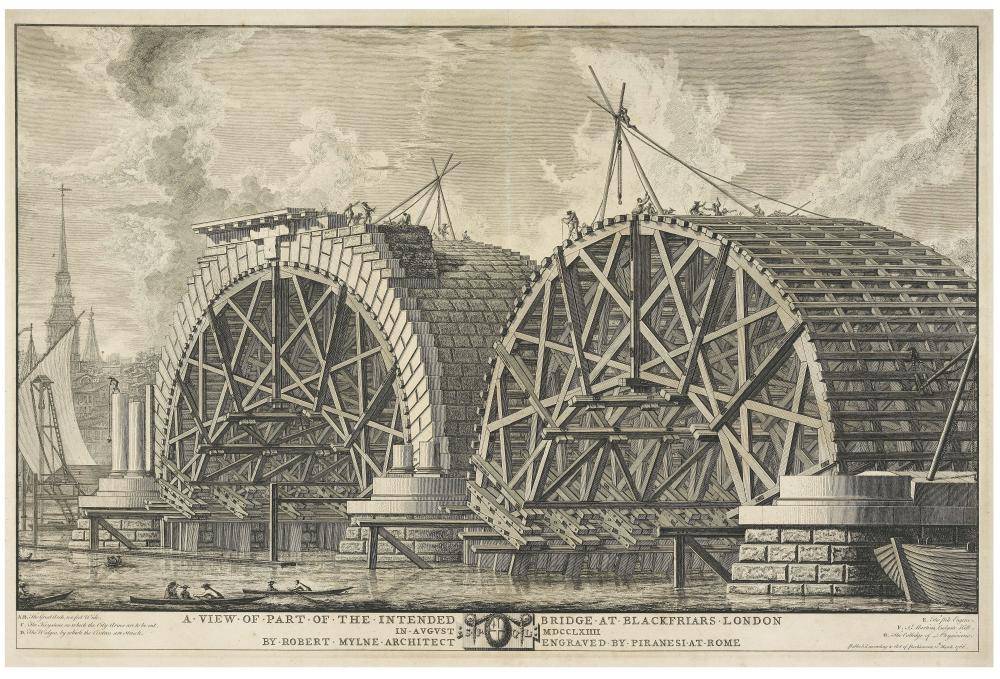

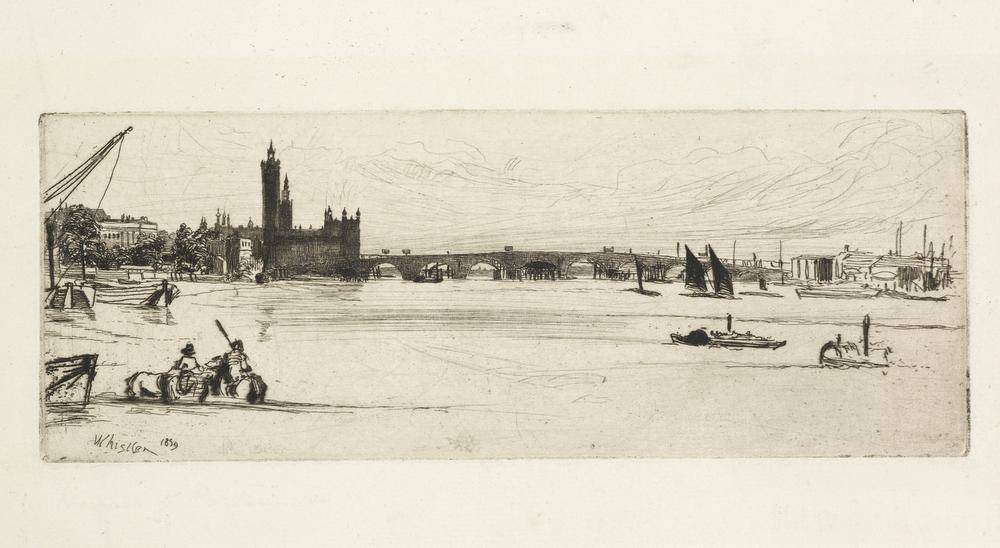

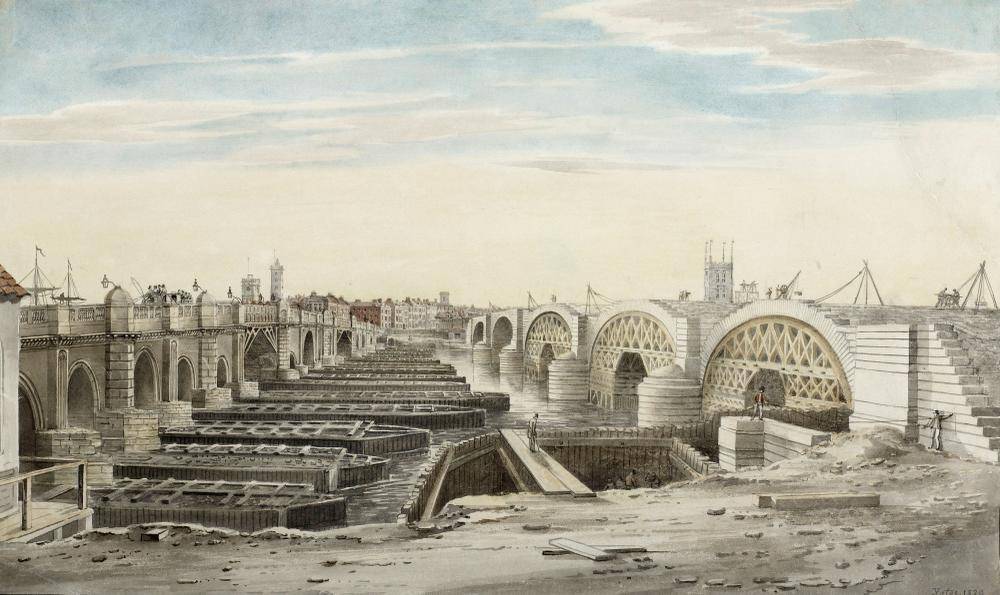

Using William Wordsworth’s 1802 sonnet Upon Westminster Bridge as a framework, Marshall collected dozens of homages to the bridge: etchings from Piranesi and Whistler; an early 20th-century oil by Charles Ginner; and more recent film and photography. They illustrate triumph or loneliness, ambition or despair. Gideon Yates’s 1829 watercolour A View from Near New London Bridge places the medieval crossing in parallel with the modern structure, the masts of ships as high as the highest steeple. Barely a century later, Henry Turner’s A Windy Evening on London Bridge captures a mob of hurried commuters, against a backdrop of construction cranes: bookends to the great Victorian building boom.

The exhibition concludes with a rendering of the recent Garden Bridge proposal by beloved London designer Thomas Heatherwick: a forested walking and cycling link near Temple Bar that will break up an interminable stretch of riverfront highway.

Bridge buffs are a considerable lot around London, but not restricted to it, of course. Many a New Yorker has found himself tangled up in Hart Crane’s 1930 poem The Bridge, but nonetheless understood the sentiment behind one of the great love letters to the Brooklyn Bridge, a Victorian-era construct that united the marginalized elements of that city. When the legendary sound artist Robin Rimbaud (a.k.a. Scanner) asked social-media followers to record themselves voicing the word “bridge” in their native language – this for an installation to be unveiled in September as part of the Museum of London show – he fielded hundreds of contributions, from Vancouver to Hanoi.

Back to when London was still Londinium, bridges were considered sacred structures, as they challenged the natural world. Archaeologists have dug up spearheads, likely offerings brought to long defunct bridges, among the ruined timber.

To better understand the thrall in which a great bridge holds us, I reached out to Stephen Nieto at the Los Angeles headquarters of the engineering and design firm AECOM. Nieto is an architect by training but serves as something of a bridge czar at the practice, merging architecture with urban design and transport. For the Chinese city of Tongzhou, for instance, his team designed twin bridges over the confluence of four rivers, which encompass a landscaped amphitheatre and waterfront promenades on multiple levels. “We look at a bridge as a place, an experience,” he says. “That’s my approach – to take bridges to the next level.”

Nieto suggests a series of intangibles that, rather subjectively, set bridges apart from more obvious crowd-pleasers like super-tall towers. The setting, for one thing. Without a remarkable backdrop, there would be no need for a bridge in the first place. “Because they bridge across mountains or large bodies of water, they develop a kind of magical appearance in terms of structure and technological innovation,” says Nieto. “We don’t really understand them. And that fascination gives them the opportunity to become iconic. … They begin to represent what that town is all about.”

Nieto reminds me that, in its time, Florence’s now iconic Ponte Vecchio was purely functional. “That’s really hard to recreate nowadays – that moment.” He cites the 27 bridges along the Los Angeles River, from the San Fernando Valley to Long Beach. “There are tons of bridges between First and 15th Street, all built at different times. Just looking at them, you can tell what year they were built, and how. They demonstrate where we are as a society – what we’ve achieved.”

The 1932 Sixth Street Viaduct is currently undergoing a high-profile redesign by architect-engineers HNTB that should elevate it from local curiosity to international icon. Yet, says Nieto, “a lot of times we overlook the fact that [bridges] facilitate the connection between communities, neighbourhoods, people,” he says. “They’re a catalyst for a better place to live.”